Curt Smith reflects on how the late Hall of Famer brought a cerebral edge to the game he loved.

Curt Smith is a senior lecturer in the Department of English at the University of Rochester. His 18 books include Voices of the Game, named one of “the 100 best baseball books ever written” by Esquire magazine. His latest is an official National Baseball Hall of Fame book, Memories from the Microphone: A Century of Baseball Broadcasting. Smith was also a speechwriter for President George H.W. Bush during and after his presidency.

“I think there is a natural bridge from being a catcher to talking about the view of the game,” Tim McCarver once said. The former All-Star baseball player and even more celebrated broadcaster died February 16, at 81, having expressed that view better than any sports analyst of his time.

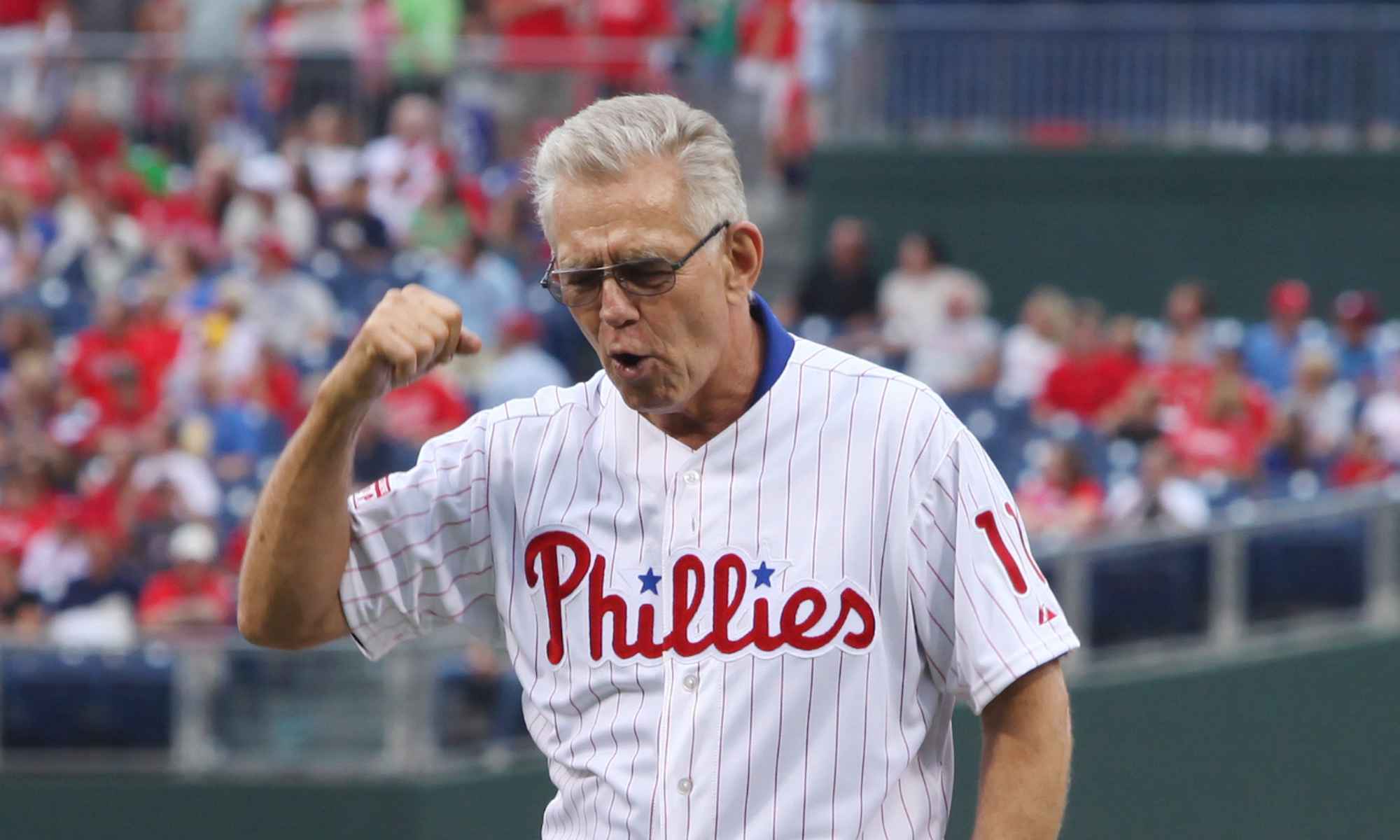

Born 52 days before Pearl Harbor, McCarver was a fine major-league catcher from 1959 to 1980—among only seven modern-day four-decade players. He was a broadcaster for even longer, becoming a Hall of Fame television analyst from 1980 to 2013, working for the Philadelphia Phillies, New York Mets and Yankees, San Francisco Giants, and St. Louis Cardinals, and almost as many networks: ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox.

The Tennessee native aired a record 23 World Series, 20 All-Star Games, 27 American or National League Championship Series (LCS), and four decades of “Game of the Week.” His vitae lists three Outstanding Sports Personality-Sports Event Analyst Emmies, seven Telly Awards, tenure on each major TV network, and six books on the sport, fusing strategy, comedy—and honesty, above all.

McCarver’s appeal flowed from knowing that baseball is not an island; rather, it is part of culture as a whole. In one breath, the Broadway junkie could compare the batting stance of Ted Williams and Stan Musial—then reference Stephen Sondheim’s “The Little Things You Do Together,” saying, “Tonight, it was the little things the Mets did together.”

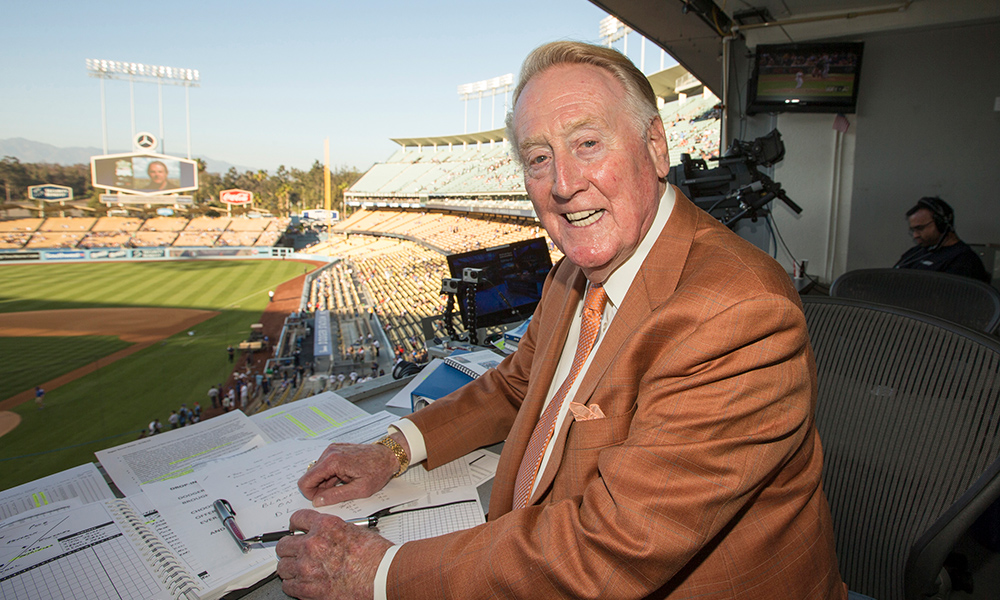

Legendary Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully said, “My best friend on a road trip is a book.” McCarver’s could be, too. In an inning, he might talk of art, note how Harry Truman had thrown “pitches left- and right-handed,” and add that “Yogi Berra would call him amphibious.” He was said to talk a lot, which was true. He also had a lot to say. McCarver’s mind was restless, his curiosity endless, his exuberance contagious. You almost never left him without learning something new.

McCarver joined the Cardinals in 1959 at 17 out of high school in Memphis, becoming the regular catcher in 1963. By 1980, his playing career had weaved through Montreal, Boston, again St. Louis, and Philadelphia. After retiring, he cohosted HBO’s series Race for the Pennant, joined NBC’s backup Game of the Week and Phillies radio/TV, and in 1983 left for the Mets’ WWOR TV. Soon, the New York Post’s Phil Mushnick wrote: “[He] has rekindled hope that sophisticated baseball has a place in New York.”

In 1984, McCarver graced the syndicated Greats of the Game and the All-Star Game and League Championship Series. A year later, ABC’s Howard Cosell released a book scalding his own network. McCarver replaced him on the World Series, clicking with play-by-play man Al Michaels. “It was like [doing] a jigsaw puzzle,” said Michaels, “and finding all the pieces.”

In 1989, Michaels, McCarver, and Jim Palmer were calling the World Series for ABC when an earthquake rocked the San Francisco area, the trio toppling to the floor. The next year, McCarver began a four-year sentence on CBS’s every-other-week Game of the Week, lack of continuity crippling ratings. In 1996, McCarver keyed Fox’s first year of coverage, the Yankees taking their first World Series since 1978 on the night after manager Joe Torre’s brother received a heart transplant. “Frank Torre is on the second day of his second heart,” McCarver said. “Joe Torre is in the fifty-sixth year of his first one. Both are overflowing.”

In 2001, the Yankees led the Diamondbacks, 2-1, in the World Series’ seventh and deciding game. Arizona loaded the bases in the ninth, Yankees closer Mariano Rivera needing two outs for another title. McCarver noted on Fox that “Rivera throws inside to left-handers, and left-handers get a lot of broken-bat hits to left, into the shallow parts of the outfield.” Pitched inside, Luis Gonzalez swung and hit the ball into short left field: D-backs win, 3-2. To legendary baseball writer Roger Angell, McCarver’s became “The Call of Calls.”

By then, the Mets had axed McCarver’s $500,000 salary, with less-pricey Tom Seaver replacing him: “a decision so small,” wrote the New York Daily News, “it could fit inside a batting glove.” McCarver joined the 1999–2001 Yanks, broadcast the 2002 Giants, then left exclusively for Fox. He received the Hall of Fame’s 2012 Ford C. Frick Award for “broadcast excellence,” did a nonpareil 14 straight World Series with Joe Buck from 2000 to 2013, and aired the 2014–2019 Cardinals on Fox Sports Midwest, coming home.

Occasionally, McCarver was asked what baseball meant to him. He said it had hurt him physically and helped cerebrally. Catching pitches behind the plate for two decades left his “left thumb twisted and torn. Fastballs and sliders are the jackhammers of the catcher’s life.” Baseball became so much a part of his life that yearly he vacationed at season’s end. “Otherwise,” he said, “I spend too much time thinking about the game.”

In 2020, he opted not to work at 78, his doctor citing COVID-19 travel safety. Baseball then bid Tim McCarver an affectionate farewell, never more than in the last few days—all of us having learned from, laughed with, and marveled at a person whose voice was the voice of a friend.