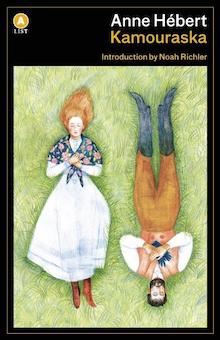

Kamouraska by Anne Hébert [Quebec Literature from P.T.]

Before starting this month’s focus on Quebec literature, I asked P.T. Smith to recommend a few books for me to read, since he’s one of the few Americans I know who has read a lot of Quebec literature. But rather than hoard these recommendations or write silly things about them, we decided it would be best if P.T. wrote weekly posts throughout February covering some of his favorite works of Quebec literature ever. You can find the first entry here.

It’s rare that I reread anything. There’re far too much sitting on my shelves and piled in stacks on my floor. I also hardly remember any details of things I’ve read. I can tell you something about why I liked a book, but not enough. I started in on my reread of Anne Hébert’s classic Kamouraska (translated by Norman Shapiro), planning on getting just far enough into it to have things to write here . . . but I don’t want to put it down, despite being in the middle of other books that I’m enjoying (like one Chad mentioned last week, Laurence Leduc-Primeau’s In the End They Told Them All To Get Lost, from QC Fiction and translated by Natalia Hero). I want to finish it because it’s gorgeous, it’s a bit frightening, and if you’re willing to let it, it’ll break your heart and punch you in the gut. If you let it. If you do the work.

If someone was asked to name the top five “important,” “classic,” and “literary” writers from Quebec, they’d go “What? From where?” But if you asked someone from Quebec, along with Ducharme, they’d almost certainly name Anne Hébert. Kamouraska is her most famous, and most widely available in English. What’s the pitch on this one besides just calling it classic? House of Anansi’s copy tells us it “is the timeless story of one woman’s destructive commitment to ideal love.” That does nothing for me. If anything, it turns me off. Timeless? Ideal love? Ehhhhh. A quote from Canadian Forum compares her to Proust, Joyce, Kafka, and Sarraute. Jesus. As a combination, it’s more meaningless than my Joyce/Salinger comparison for Ducharme last week. Oh, the other quote throws out Brontë. I actually like Brontë (Charlotte, I assume), but that’s not really a selling point anymore.

If someone was asked to name the top five “important,” “classic,” and “literary” writers from Quebec, they’d go “What? From where?” But if you asked someone from Quebec, along with Ducharme, they’d almost certainly name Anne Hébert. Kamouraska is her most famous, and most widely available in English. What’s the pitch on this one besides just calling it classic? House of Anansi’s copy tells us it “is the timeless story of one woman’s destructive commitment to ideal love.” That does nothing for me. If anything, it turns me off. Timeless? Ideal love? Ehhhhh. A quote from Canadian Forum compares her to Proust, Joyce, Kafka, and Sarraute. Jesus. As a combination, it’s more meaningless than my Joyce/Salinger comparison for Ducharme last week. Oh, the other quote throws out Brontë. I actually like Brontë (Charlotte, I assume), but that’s not really a selling point anymore.

The first thing I tell people about the book is that the voice switches between third and first person, where initially third is dominate, but the first takes over, more and more, though third never disappears completely. That’s interesting, right? It’s no gimmick, not a thing where the voice switches between sections, but intricate movement, changing mid-paragraph, the voice of a woman confronting her past, a woman judging herself and others, a woman who detaches from her multiple selves, because they exist for others, because others act on and create those names and identities, but somewhere beyond all that is an “I” that is for her, for her most sincere connections, and from there she can try and understand what she has done and what others too. Because this is a patient book, one where Hébert is masterfully in control of pacing, the clearest she states it comes well into the book, once you’ve already found your grounding:

The first thing I tell people about the book is that the voice switches between third and first person, where initially third is dominate, but the first takes over, more and more, though third never disappears completely. That’s interesting, right? It’s no gimmick, not a thing where the voice switches between sections, but intricate movement, changing mid-paragraph, the voice of a woman confronting her past, a woman judging herself and others, a woman who detaches from her multiple selves, because they exist for others, because others act on and create those names and identities, but somewhere beyond all that is an “I” that is for her, for her most sincere connections, and from there she can try and understand what she has done and what others too. Because this is a patient book, one where Hébert is masterfully in control of pacing, the clearest she states it comes well into the book, once you’ve already found your grounding:

It’s not the unrelenting light. No, it’s this terrible stillness. This distance that ought to be comforting me, this sense of detachment. It’s worse than all the rest. Seeing yourself as someone else. Pretending to be objective. Not feeling that you and that young bride are one and the same.

More concretely: Kamouraska is based on a true story. In the early nineteenth century, Elisabeth d’Aulnières married Antoine Tassy, well-off, land-owning man, “squire” of Kamouraska. He’s awful to her. She falls in love with an American doctor and murders Tassy. Later, she remarries. Years later, many, many children later, that husband is dying, and it’s time for Elisabeth to turn towards her memories, confess her past to herself. The movements from pasts to the present and back can happen quickly, though as the novel goes on, the story of her life with Tassy becomes more and more linear, more consistently told. At first she is afraid to go there, to think of the horrors she lived through, and the horror she inflicted, not only murdering Tassy.

More concretely: Kamouraska is based on a true story. In the early nineteenth century, Elisabeth d’Aulnières married Antoine Tassy, well-off, land-owning man, “squire” of Kamouraska. He’s awful to her. She falls in love with an American doctor and murders Tassy. Later, she remarries. Years later, many, many children later, that husband is dying, and it’s time for Elisabeth to turn towards her memories, confess her past to herself. The movements from pasts to the present and back can happen quickly, though as the novel goes on, the story of her life with Tassy becomes more and more linear, more consistently told. At first she is afraid to go there, to think of the horrors she lived through, and the horror she inflicted, not only murdering Tassy.

The memories burst through her present contemplation of death, triggered by little thoughts and little moments. There are multiple pasts, the time before her marriage, when her aunts molded her into a “proper lady” in Catholic Quebec, the early days of meeting her husband, the time after his death, and most persistently, the time of her trial for his murder. It’s the trial that most frequently forces its way to her consciousness, so much so that she speaks defenses of herself to a nameless judge, sometimes defenses of actions well after and not involving the murder.

At times the movements are hard to follow, much as third- and first-person perspective overlap, so do pasts and presents. The more she contemplates that life before, the more comfortable she becomes there, or maybe she’s not comfortable, but it becomes more and more difficult to escape, more necessary to reside in:

That time. That one time. A certain time of my life, moved back to, into like an empty shell. Enclosing me again. With the sharp little click of an oyster snapping shut. I’m forcing myself to live within this narrow space. I’m settling into the house on Rue Augusta. I’m breathing its rarefied air, an air I’ve already breathed before. I’m taking the steps I’ve already taken. There is no Madame Rolland. Not anymore. I’m Elisabeth d’Aulnières, the wife of Antoine Tassy. I’m pining away. Dying, dying. I’m waiting for someone to come and save me. I’m nineteen years old . . .

Spoiler: no one saves her. Why would someone save her? Sure, a lover comes along, but is she saved? Or is she just condemned to a different form of punishment? I don’t fully remember the end, but with a hundred pages to go on the reread, and given the state Elisabeth was in when I stopped to write this, I’m pretty sure it’s the latter.

Kamouraska is a cruel book. That’s one of the things I admire about it. It’s also a compassionate book. It’s haunting. Elisabeth d’Aulnières married an awful man when she was a child. He cheats on her openly, he abuses her. He rapes her. And like a proper lady of the time, like a woman raised in religious Quebec, she’s meant to let him, because what’s marital rape, right? So she kills him. She doesn’t regret this, but she still lives with guilt. She feels for her younger, broken self. But she also feels for this man who was tormented, who was not only violent towards her, but towards himself. The doctor who she loves, he’s not an innocent either. There are no innocents, not the other women involved with her husband, not her husband, not herself. Maybe her new husband, but probably not, after all, she birthed him many children, and was that a choice? But every single person enacts cruelty. Every single person her narrative aggresses towards, and boy does it come at people, she also opens her heart to. Which itself causes her pain.

Kamouraska is a cruel book. That’s one of the things I admire about it. It’s also a compassionate book. It’s haunting. Elisabeth d’Aulnières married an awful man when she was a child. He cheats on her openly, he abuses her. He rapes her. And like a proper lady of the time, like a woman raised in religious Quebec, she’s meant to let him, because what’s marital rape, right? So she kills him. She doesn’t regret this, but she still lives with guilt. She feels for her younger, broken self. But she also feels for this man who was tormented, who was not only violent towards her, but towards himself. The doctor who she loves, he’s not an innocent either. There are no innocents, not the other women involved with her husband, not her husband, not herself. Maybe her new husband, but probably not, after all, she birthed him many children, and was that a choice? But every single person enacts cruelty. Every single person her narrative aggresses towards, and boy does it come at people, she also opens her heart to. Which itself causes her pain.

It’s a beautiful book. It’s a feminist book. It’s at times a difficult book, because of the prose, because of the emotions at stake. It’s accessible because of that heart, because in the end it wants to connect, Elisabeth wants to have her voice heard, needs to have it heard. It’s a Quebecois book. The deep religiosity of the region is inescapable for her. Read it for all of these reasons. It does things you haven’t seen before, I promise you, and how many books do that?

Now, the final factor in why I picked this book? Because it touches on my home, on Vermont. That I’m so close to Quebec is only one of the reasons I’ve tried to read so much from the province. When the books cross into my land, it touches me a little.

Find my love, at the end of the earth. In Burlington. Burlington. The United States.

P.S. I’ve got two others for you. First: another book where I think the perspective of the voice is more of a reason to read than any plot description: Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette’s Suzanne, translated by Rhonda Mullins. A finalist for last year’s BTBA (Peter McCambridge wrote the Why This Book Should Win post), this book is about a relationship between a woman and her grandmother . . . but it’s written in second person, to the grandmother, about her life. It does wonderful things with that. It’s also another portrayal of just how intensely Catholicism ran Quebec life, until rather recently. Second: Marie-Claire Blais’s These Festive Nights, translated by arguably the GOAT translator of Quebec lit: Sheila Fischman. I force it in here because like the jacket copy of Kamouraska compares it to Brontë “but modern in style and explicitness,” except way, way, more accurately, let’s say that These Festive Nights is Woolf, but modern in style and explicitness.

P.S. I’ve got two others for you. First: another book where I think the perspective of the voice is more of a reason to read than any plot description: Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette’s Suzanne, translated by Rhonda Mullins. A finalist for last year’s BTBA (Peter McCambridge wrote the Why This Book Should Win post), this book is about a relationship between a woman and her grandmother . . . but it’s written in second person, to the grandmother, about her life. It does wonderful things with that. It’s also another portrayal of just how intensely Catholicism ran Quebec life, until rather recently. Second: Marie-Claire Blais’s These Festive Nights, translated by arguably the GOAT translator of Quebec lit: Sheila Fischman. I force it in here because like the jacket copy of Kamouraska compares it to Brontë “but modern in style and explicitness,” except way, way, more accurately, let’s say that These Festive Nights is Woolf, but modern in style and explicitness.

I have been haunted by this book. For some

reason it doesn’t want to leave me.