“Next Episode” by Hubert Aquin [Quebec Literature from P.T. Smith]

Before starting this month’s focus on Quebec literature, I asked P.T. Smith to recommend a few books for me to read, since he’s one of the few Americans I know who has read a lot of Quebec literature. But rather than hoard these recommendations or write silly things about them, we decided it would be best if P.T. wrote weekly posts throughout February covering some of his favorite works of Quebec literature ever. You can find his earlier entries here.

In 1964, Hubert Aquin was arrested on charges of illegal possession of a firearm, the and apparently police he was a revolutionary. While held in a psychiatric hospital in Montreal for four months, he wrote Next Episode. The narrator of Next Episode is a man held in a psychiatric hospital in Montreal, writing a first-person spy thriller about a man from Montreal who is a political revolutionary. It’s a short, strange book. It’s philosophical, it’s absurdly rambly, another book where the narrator is chasing, chasing his thoughts, desperate to order them, language running itself away from him. In the beginning, the narrator in the hospital attempting to write and the narrator in Geneva battle for space. The first fights to give life, to find a way to free himself in some form, and eventually it becomes almost a straightforward quickly-paced, tense thriller, at times.

In 1964, Hubert Aquin was arrested on charges of illegal possession of a firearm, the and apparently police he was a revolutionary. While held in a psychiatric hospital in Montreal for four months, he wrote Next Episode. The narrator of Next Episode is a man held in a psychiatric hospital in Montreal, writing a first-person spy thriller about a man from Montreal who is a political revolutionary. It’s a short, strange book. It’s philosophical, it’s absurdly rambly, another book where the narrator is chasing, chasing his thoughts, desperate to order them, language running itself away from him. In the beginning, the narrator in the hospital attempting to write and the narrator in Geneva battle for space. The first fights to give life, to find a way to free himself in some form, and eventually it becomes almost a straightforward quickly-paced, tense thriller, at times.

I wrote about Aquin for Quebec Reads back when I first read him, taking on both Next Episode and Invention of Death. I remember nothing of what I wrote, and my past self is always an ignorant moron wholly unaware of what he’s writing, so I refuse to revisit it. If you want, you can.

Last week, in my P.S. note, I acknowledged Sheila Fischman as the GOAT when it comes to translators from Quebec. Guess who translated the version of Next Episode I’m familiar with? There’s an earlier translation, but I’ll stick with hers. I also should have noted that while she didn’t translate Kamouraska, she did much of Hébert’s other work that has made it to English.

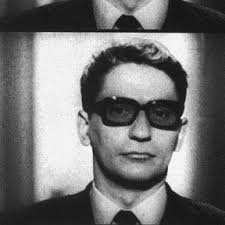

This is a little bit of a different recommendation than my posts on Ducharme and Hébert. Aquin is classic too, but a little less central, from my outside viewpoint. A little more of a literary oddball. If Ducharme’s image is the myth of the recluse Aquin’s has the myth of the rebel and the suicide: he killed himself at forty-seven. He was expressly political, unlike those two . . . I think. In the 60s, when he was arrested, he was a member of the Quebec liberation movement, though not the more radical FLQ (Quebec Liberation Front). Infinite Jest may play the idea of Quebec liberation as a joke, but in the 60s and culminating in the October Crisis in 1970, it was not.

This is a little bit of a different recommendation than my posts on Ducharme and Hébert. Aquin is classic too, but a little less central, from my outside viewpoint. A little more of a literary oddball. If Ducharme’s image is the myth of the recluse Aquin’s has the myth of the rebel and the suicide: he killed himself at forty-seven. He was expressly political, unlike those two . . . I think. In the 60s, when he was arrested, he was a member of the Quebec liberation movement, though not the more radical FLQ (Quebec Liberation Front). Infinite Jest may play the idea of Quebec liberation as a joke, but in the 60s and culminating in the October Crisis in 1970, it was not.

I do something a little bit, a little slightly but not totally, dishonest with this novel. I recommend it to anyone who likes Jean-Patrick Manchette. It’s a little dishonest because if anyone ever takes me up on it, in the early pages—when it’s mostly a possibly insane man obsessed with revolution, independence, language, and love is writing about trying write a novel while barely maintaining a line of thought—they’re going to be confused to all hell as what I was going on about:

Real novels I leave to the real novelists. As for me, I flatly refuse to bring algebra into my invention. Condemned to a certain ontological incoherence, I take my stand. I’m even turning it into a system with an immediate application that I decree. Infinite I shall be, in my own way and in the literal sense. I won’t a system I create for the sole purpose of never leaving it.

Yet . . . most of the people I know who like Manchette would also like Next Episode. There are similarities. I’m not completely misleading them. The people I know are also the type to be drawn in by the oddities, the madness, of Next Episode. And when the thriller takes off, they’ll see the Manchette. In my head, there are maps of literature, and Aquin and Manchette share an open border. Along that border violence and the political are a conjoined part of life, or at least a place sympathetic to the possibility of violence as a political path for the underdog, the one confined by those with power.

Early on, our narrator is trying to figure out how to write this thriller. What sentences should be like, what the plot should be, who the characters are:

As quickly as I can, I eliminate any behavior that would give my secret agent too much merit: he’s neither a Sphinx nor a highly perceptive Tarzan, neither God not the Holy Ghost; he musn’t be so logical that the plot need not be or, on the other hand, so lucid that I can complicate everything else and cook up some story that makes no sense, that when all’s said and done would only be understood by some bungling oaf with a gun who doesn’t share his thoughts with anyone.

As he struggles, moving back and forth from the psychiatric institute to the plot, the propulsive madness of his language overlaps the two. The narrator exists both as the spy and as the man in the hospital. Aquin is having fun, I need to be clear. He’s mad and wild and angry but he’s having fun.

As he struggles, moving back and forth from the psychiatric institute to the plot, the propulsive madness of his language overlaps the two. The narrator exists both as the spy and as the man in the hospital. Aquin is having fun, I need to be clear. He’s mad and wild and angry but he’s having fun.

The spy is given a mission by another invention of the narrator, a man named Hamidou Diop. He is to find and kill a man who may have (there is no certainty here) cut off the FLQ’s Swiss bank account. After meeting with K, the revolutionary’s lover, this book’s version of the femme fatale, he acquires a car, and flies off on mountain roads. On his way, the language of the writer and the spy overlap:

Time passes and I take forever to cross the Col des Mosses. Each turn surprises me in third gear when I should have already started to gear down; each sentence disconcerts me. I burn words, stages, memories, and I keep freeing myself from the tracery of this interpolated night. The event that’s already too far ahead of me will unfold shortly . . .

Aquin is having fun. It’s his fun. It’s weird. It matters. It’s sincere. It’s not like this book is laugh out loud funny, but man: “I needed to think up a quick retort, and since I no longer had a weapon to draw, I’d have to empty my dialectical magazine on this stranger who was standing between me and the daylight.”

Next Episode is a thriller, but also, somehow, nothing really happens. It’s a book of passionate desire for action, a raging need to attack the world, change it, free the individual from confinement, and free a nation under the rule of another nation. It’s also a book of confusion, of paralysis and impossibility, anxious desire for action but absolutely inability to act. Identity doesn’t work. Our revolutionary is kidnapped, he escapes, he kidnaps his kidnapper, he escapes. At no point is he sure that the other man is indeed his target, they go so far as to tell each other the same lies, or one lies and the other mirrors with truth. Even when our revolutionary breaks into his enemies’ house to wait for him, with the aim of finally killing him, he’s uncertain about everything.

Next Episode is a thriller, but also, somehow, nothing really happens. It’s a book of passionate desire for action, a raging need to attack the world, change it, free the individual from confinement, and free a nation under the rule of another nation. It’s also a book of confusion, of paralysis and impossibility, anxious desire for action but absolutely inability to act. Identity doesn’t work. Our revolutionary is kidnapped, he escapes, he kidnaps his kidnapper, he escapes. At no point is he sure that the other man is indeed his target, they go so far as to tell each other the same lies, or one lies and the other mirrors with truth. Even when our revolutionary breaks into his enemies’ house to wait for him, with the aim of finally killing him, he’s uncertain about everything.

I’m going on and on, aren’t I? This is a . . . unique book? It’s somehow stranger than I remember. It’s a love story, but the identity of that lover, K., is another identity without certainty. The love too is political:

What triumph there was in that night! What violent and sweet foretaste of the national revolution was unfolding on that narrow bed awash in colours and our two bodies naked, blazing, united in their rhythmic madness. Again tonight my lips hold the damp taste of your boundless kisses.

It’s simultaneously a political allegory and blatantly straightforward that its protagonist is a violent political separatist working for Quebec independence from Canada. At times, when our man from Montreal is walking around Geneva, being idle and paranoid, it’s the novel of a flâneur. It’s a novel about writing a novel. It’s a goddamned Quebec book. Its entire attitude, it is Quebec:

Within myself, explosive and depressed, an entire nation grovels historically and recounts its lost childhood in bursts of stammered words and scriptural raving, and then, under the dark shock of lucidity, suddenly begins to weep at the enormity of the disaster, at the nearly sublime scope of its failure.

P.S.: It’s impossible for me to not tag in Alain Farah’s Ravenscrag, translated by Lazer Lederhendler (which I reviewed for Mookse and the Gripes). Another novel with blended narratives, this time in two time periods. It’s about MK-Ultra. (Isn’t that enough of a pitch? It is for me.) It’s about the absolutely insane experiments actually done by a doctor at McGill. It also features another version of Next Episode’s Hamidou Diop. Jason Freure wrote about this revival of Diop for the Montreal Review of Books. Read Boundary too, by Andrée Michaud in Donald Winkler’s translation. A much more straightforward literary crime novel set in the woods on the border between Quebec and Maine. A book I thought was pretty good when I read it . . . and months later I realized was more than that and I need to read more Michaud. And Donald Winkler? He’s not only married to Sheila Fischman, but contends with her for that GOAT title.

P.S.: It’s impossible for me to not tag in Alain Farah’s Ravenscrag, translated by Lazer Lederhendler (which I reviewed for Mookse and the Gripes). Another novel with blended narratives, this time in two time periods. It’s about MK-Ultra. (Isn’t that enough of a pitch? It is for me.) It’s about the absolutely insane experiments actually done by a doctor at McGill. It also features another version of Next Episode’s Hamidou Diop. Jason Freure wrote about this revival of Diop for the Montreal Review of Books. Read Boundary too, by Andrée Michaud in Donald Winkler’s translation. A much more straightforward literary crime novel set in the woods on the border between Quebec and Maine. A book I thought was pretty good when I read it . . . and months later I realized was more than that and I need to read more Michaud. And Donald Winkler? He’s not only married to Sheila Fischman, but contends with her for that GOAT title.

Leave a Reply