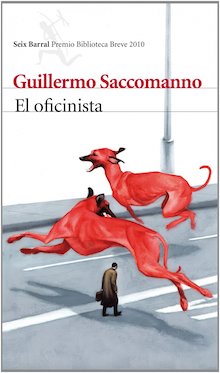

“The Employee” by Guillermo Saccomanno [Excerpt]

You have three days left to take advantage of Guillermo Saccomanno’s status as “Open Letter Author of the Month.” Through Thursday night, you can get 30% off both of his books via the Open Letter website by using the code SACCOMANNO at checkout.

With so many positive comments coming in about 77, I thought I’d give you a little tease and run a bit of the next Saccomanno book we’ll be publishing.

Here’s the description of The Employee from the Carmen Balcells site:

Perfectly normal men and women head to their desks every day in a city laid waste by guerrilla incursions, menaced by hordes of starving people, murderous children and cloned dogs, patrolled by armed helicopters, and plagued with acid rain. Among them is an office worker willing to be humiliated in order to keep his job – until he falls in love and allows himself to dream of someone else.

To what depths is a man willing to go to hold on to a dream? El Oficinista tells a story that happened yesterday, but still hasn’t happened, and yet is happening now. And we didn’t even notice, too tied up in our jobs, our salaries, our appearances. This novel embraces an anti-utopia, a world of Ballard but also of Dostoyevsky.

And if that isn’t intriguing enough, here’s a blurb that might whet your interest:

“A strange book in the best sense of the word. This is not an ordinary novel, it will surprise many.” Rodrigo Fresán

The Employee by Guillermo Saccomanno, translated from the Spanish by Amanda DeMarco and Sebastián Pont Vergés

. . . so extreme an experience of solitude that one can only call it Russian.

—The Diaries of Franz Kafka

1

At this hour of night, military helicopters circle the city, bats flutter before the large office windows, and rats slip between the desks, all of which are plunged into darkness except for one, his, with the computer on, the only one on at this hour. The employee feels something brush swiftly over his shoes. A faint squeal rushes past along the carpet and slips off into the blackness. He turns his gaze away from the monitor and sees the winged shadows in the night outside. Then he consults his pocket watch, stacks up a few files, places the checks in a folder for the boss to sign tomorrow, and stands to leave. He moves slowly, and not only out of fatigue. Also out of sorrow.

The computer takes a long time to shut down. Finally the screen sighs, goes black. He fastidiously arranges the tools of his work for the coming day: pens, inkwell, stamps, ink pad, eraser, pencil sharpener, and letter opener. The letter opener receives preferential treatment. He polishes it. The letter opener seems harmless. But it can be used as a weapon. He also seems harmless. But looks can be deceiving, he tells himself.

He likes to think that despite his docile nature, under the right circumstances he could be ferocious. If the circumstances arose, he could be different. No one is what they seem to be, he thinks. The opportunity simply had to present itself, then he would demonstrate what he was capable of. This reasoning helped him to endure the boss, his coworkers, and his own family. Neither at home nor in the office did anyone know who he was. And when he considered that he himself didn’t know either, it made him giddy. One of these days, they would see. Just when they least expected it. It frightens him to think that just like his boss, his coworkers, and his family, he has no idea what he is capable of. Sometimes, when he copies the boss’s signature—and he could copy it perfectly—he asks himself who he is. He copies the boss’s signature secretly. The fact that someone can copy someone else doesn’t make them someone else. On more than one occasion, he had asked himself who he was, who he could be, if he could be someone else, but he was frightened to find out. On more than one occasion it had crossed his mind to forge the boss’s signature on a check, cash it, and run. If he hadn’t done it by now, he reflects, it’s because he doesn’t have anyone to share the loot with. A momentous act can only be motivated by passion. In the films, the hero always had a motive: a woman. If you were crazy about a woman, you were unwavering.

He arranges his office supplies, each in its place. Organizes them with mad meticulousness. And, after setting each one down, he glances over his shoulder. At the desk behind his, where his nearest coworker sat. Although this coworker wasn’t his subordinate and was charged with less important tasks than his, nonetheless, someday, when the employee was no longer there, the coworker would certainly sit at his desk.

On more than one occasion, he had caught him in the act of writing in a notebook. When the coworker sensed he was being observed, he swiftly stowed the notebook in a desk drawer with an obsequious smirk. Finally, he confronted him. What was it he was writing, he asked. Terrorized, the coworker answered, a diary, he was keeping a diary, a personal one. He didn’t know what to say. Keeping a diary was for girls, he thought. Maybe the coworker was a homosexual. He didn’t seem like one, but he could be. With others, you never knew. He stammered something about how keeping a diary seemed very interesting. It never would have occurred to him that the life of someone who spent his entire life at a desk could be interesting, he thought. But he didn’t say so. One night like this, alone in the office, he’d rummaged around in the drawers of his coworker’s desk. The notebook wasn’t there. Then it occurred to him that these secret writings must contain something against him. Why shouldn’t he think that the coworker had been assigned to record his movements. Were it so, he told himself, even if he had always considered himself an obliging employee and an ordinary citizen, he now found himself under surveillance. This feeling of being under surveillance persisted for quite some time. Until, after a while, he stopped worrying about it: had the coworker been an agent and he a suspect, he soon would have disappeared. The roles were reversed. No longer under surveillance, he surveilled. When he turned abruptly, the coworker rushed to close the notebook with this smirk of apology, which turned into a game that ultimately bored him. Since then he’d been certain that if he could, the coworker would take advantage of the smallest error on his part, with that same smirk, in order to move up a desk. Around here, you couldn’t even trust your own shadow. And the coworker behind him, he thinks, is his shadow. A menacing shadow, even if it smiled amicably and always proved willing to sort out whatever file he consigned to it.

The employee regards the letter opener. It would be lethal, were he to drive it into his coworker’s jugular. He reproaches himself for having this sort of fantasy. He is aware that it degrades him. It makes him feel contemptible. As contemptible as the rest of them. At heart, he is convinced that he’s better than the others. If an opportunity were to present itself, he could demonstrate that he is above them, and that his superiority lies squarely in never stabbing anyone in the back to get a raise, a promotion. He considers himself better than everyone else precisely because in all of the years he’s spent here, he’s never tried to get ahead by slandering his fellow employees. You might also say, he tells himself, that his behavior suggests a dogged desire to go unnoticed. If during his tenure he had never been the object of disciplinary action and had managed to endure at his desk, he reflects, it was only thanks to his particular way of melding with his surroundings, which guaranteed that no one took any note of him. He sometimes wondered if to convince the others that he was harmless, he would first have to persuade himself of the fact. Once his thoughts had advanced to this phase, they galled him. It was possible he had expended so much effort pretending he wouldn’t harm a fly, that he was now actually incapable of doing so. But, at the same time, he reflects, someone like him, capable of thinking two contradictory ideas at once, was not only superior to the others but also someone to be feared, someone who could commit a courageous act at the moment they least suspected, confronting them with their own cowardice. Watch out, he says. Watch out for me. Because I’m someone else. Just because I don’t show it now doesn’t mean that the others should underestimate me if the opportunity presents itself. And of all of them, the one who should take the most care was of course the coworker.

His desk now in order, he heads toward the coat rack, pulls his raincoat from its hook. He’s embarrassed to wear it. It isn’t merely worn but actually deformed with age. With the cold these past weeks, the temperature dropping day by day, he’s had no alternative but to use it. Each morning before entering the building, he takes it off, folds it, and keeps it folded under his arm with the lining facing out, which he’d paid a Bolivian tailor in his neighborhood to replace last year. In the office, he glances around slyly before hanging the raincoat on a rack far from his desk, in a nook, at the back. Then he slips away. He worries that his haste will make his uneven gait more pronounced. He generally manages to lessen his limp by taking measured strides. But when he abandons his raincoat on the rack, it’s difficult not to run away, so that no one associates it with him. Conversely, alone in the office at this hour of the night, he takes down the raincoat and slips it on calmly. Then he turns off the light and sets out, shrouded in darkness. He can make his way blindly between the desks, such is his knowledge and instinctive memory of the place, its desks, archives, and cabinets; its odd corners.

But a noise stops him in his tracks. It’s not the rats. It’s footsteps.

2

A shadow falls on the frosted glass window of the boss’s office. He watches it slip across the pane, silhouetted by the helicopters’ search lights. No one except him stays this late at the office. No one puts in as much overtime. And he doesn’t do it because he has to. Also because he wants to. He prefers to stay away from home for as long as possible. But tonight his dread makes him regret staying so long. He creeps up on the shadow behind the frosted glass window, letter opener in his damp hand, his entire body gripped by fear.

He pricks his ears. Footfalls from the other side. If these are the steps of a thief, and if he, bumbling but heroic, manages to overpower him, his actions will be rewarded by the boss, perhaps even canceling the debt incurred by the advances he takes on his salary. He clutches the letter opener, which does nothing to soothe his fears. He tiptoes, without betraying his limp, taking care that his well-worn shoes don’t squeak. He crouches to one side of the door.

The steps on the other side pause. The silence lengthens. He’s afraid that his courage will fail him. His entire life has been marked by subjugation, maybe now is his big chance. If he lets it slip through his fingers, he might not get another. And the memory of this night, he knows, would be just another disappointment among countless in his life.

He’ll wait until the intruder exits the office, charge him, catch him by the neck, and disarm him with the letter opener at his throat, for the intruder certainly had a weapon, a firearm. He will seize the firearm and, holding him at gunpoint, call the security guards.

The shadow grows across the floor as the door swings open.

3

He tenses to attack. Then restrains himself. The secretary panics at the sight of him crouching there, about to stab her with the letter opener. Her glasses fall to the ground. He’s speechless. He picks up the young woman’s glasses, a round-rimmed pair, while stammering an explanation and still clutching the letter opener. The young woman trembles. He sets the letter opener on a desk. Helicopter search lights shine through the windows. He sees the glittering of her tears. Wishing to soothe her, he takes her in his arms.

Leave a Reply