Coach House Books & Marie-Claire Blais [2018 Redux]

I’ve really, really enjoyed Quebec Month here at Three Percent. I had the chance to read the Catherine Leroux book I’ve been wanting to read, encountered some other really great books and presses I probably would’ve missed if I hadn’t forced this on myself, and got to run a few really cool interviews and excerpts. On top of that, P. T. Smith has expanded my to-read bookshelves with Next Episode, a horror book about a nunnery, Go Figure and Ravenscrag.

Based on Twitter (never reliable!), it seems like people are liking this new Three Percent focus (especially the interviews), and personally, I’m much happier reading a bunch of great books from a particular place than I was when trying to read and write about recently published translations every week. Too much mediocrity that gets lauded for being new, in my opinion. It’s hard not to want to dig into—and criticize—the book industry when you’re watching sausage turn into gold. It’s probably for the best to just read in a bubble than to try and engage with the hipster websites and all the over-the-top exaggerated praise for every new book.

This is my new life mantra: If you want to avoid being depressed, stop paying attention to most everything.

*

The one author who I didn’t get to, but desperately wanted to was Marie-Claire Blais. I’ve been recommended her books from one friend or another for more than fifteen years now, and . . . I own a few. Although A Season in the Life of Emmanuel is frequently referred to has her most beloved book, I really wanted to read part of her ten-volume (?!) series called Soifs (Thirsts). Wikipedia blows at delineating which of her books are part of this series and which aren’t, but I bought a few from House of Anansi (another Canadian press we never featured properly because time) and really hoped to read These Festive Nights this month.

I don’t care what’s cool, I like all these covers. Like the one for Rebecca, Born in the Maelstrom:

Or Thunder and Light:

And, last but not least, Augustino and the Choir of Destruction:

As I said last week, I am a sucker for trilogies and the like, and far too often, male authors with long literary series (*cough* KNAUSGAARD *cough*) get tons of media play, but women with equally ambitious projects (Dorothy Richardson, Doris Lessing, Marie-Claire Blais) are ignored. I’m as guilty of this as anyone; see the fact that I’m going to dedicate March to losing my mind over Uwe Johnson’s Anniversaries, but have yet to read Marguerite Young’s Miss MacIntosh, My Darling or Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans.

This needs to be rectified.

And I want to start with Blais.

Her books sound so up my alley . . . Here’s the copy from These Festive Nights:

Originally published in 1995 under the title Soifs, the first novel in Marie-Claire Blais’ masterful series won the Governor General’s Award for French Fiction and was hailed by critics around the world as a tour de force, comparing Blais to such literary greats as Virginia Woolf, Dante, Sophocles, and Shakespeare. In this dazzling rendering, These Festive Nights, celebrated translator Sheila Fischman brings Blais’ novel to life for English-speaking readers.

A sun-drenched paradise in the Gulf of Mexico surrounded by the glimmering blue sea; Renata is convalescing on this island poised between two worlds: between great wealth and extreme poverty, between the past and an uncertain future, between the beauty of the world and the horrors of history.

During her time here, Renata becomes tormented by thirst—for justice, for pleasure, for intoxication—while all around her, festivities are going on in joint celebration of the birth of baby Vincent and the end of the twentieth century. Over the course of three days and three nights a flock of characters assembles: wealthy, poor, writers, artists facing their own mortality, children immersed in innocent games, young men dying of AIDS, refugees, the Ku Klux Klan—an entire spectrum of humanity is depicted in the grip of doubt and suffering. In this swirling, baroque fresco, Marie-Claire Blais captures the essence of our apocalyptic age, rendering it in powerfully evocative prose.

Also, this 300-page novel might be just one sentence? (Or, like, three sentences?) How in the world haven’t I read this?

OK, it might not happen in April or May, but before the fall, I will dedicate a month to reading all of her books from this series that have been translated into English. And separate from writing for this website, I’ll finally read Young’s masterpiece AND Doris Lessing’s Children of Violence series.

And maybe this project will give me a chance to finally interview Sheila Fischman . . . Who WAS profiled in The Walrus! (Thanks Jeffrey Zuckerman!)

*

All of that above, and the acknowledgement of this disparity in coverage and general respect has me a bit bummed out. I love long books. I’m planning on spending upwards of eight months reading Against the Day slowly but surely via audiobook, Kindle, and a treadmill. (When you run a half marathon for fun, at the gym, alone, and get through less than 6% of a book, you know it’s gonna be a commitment.)

That all said, Michigan State beat Michigan on Sunday (even with two of their best players sidelined), and I’ve totally come to terms with my lost files (if anyone wants to try and hack a “inprogress” “sparsebundle” TimeMachine backup file, let me know and I’ll give it to you and you can be an Open Letter superhero), and want to ease back into writing things that are more than just cheerleader-type posts for interesting books.

Not that I don’t want to write about good books, but there have to be more creative ways to talk about literature. Like how Sam Miller writes about baseball . . .

Which, actually, speaking of Sam, his recent article on a “small-market team’s worst nightmare” might actually speak to this whole Quebec focus and everything else I always wring my hands over when it comes to non-profit publishing. But let’s get to that in a minute. First: Let’s get our murder on.

The Laws of The Skies by Grégoire Courtois, translated from the French by Rhonda Mullins (Coach House Books)

I’m tempted to title this post “Seven Highs of Guilty Pleasures,” but I don’t think I actually want to try and come up with seven things about this book that would justify such a title. My take on this book—which is pretty good, but definitely isn’t high literature—is this: The first 30 pages are funnier than I expected and left me yearning for some killing.

Which sounds dark! But The Laws of the Skies declares its intention from the very first page, leaving the reader with a very clear idea of what’s going to happen:

The moms and dads had said goodbye to them through the school bus windows. Some of the children were crying as they waved goodbye, and others were chattering with each other as if they had never had parents. It was the first time any of them would be away from their home, their bed, and their blankie. [. . .]

And there you have it.

The children were on their way.

They would never return.

Cool, cool! Perfect book for a camping trip!

This is the sort of book that I enjoyed while I was reading it (I guess? I skimmed a bit and felt like it was all too obvious from moment to moment), but that I have almost nothing to say about it as soon as I set it aside.

Looking through my tagged pages in my galley, there’s nothing that I marked that wasn’t just a plot point. Enzo brains the teacher. Some ill-defined kid falls down a hill and bleeds out. A bunch of random kids eat poison berries and puke till they die.

Cool. Cool.

The best part, in my opinion, is when Sondra’s husband shows up drunk to drive sick Natalie home. Which isn’t funny, except. His section is all about how excited he is that his wife and kid are gone for the weekend so that he can finally drink some whiskey in peace and quiet and jack it. And then, of course, his wife calls and asks for a favor. MARRIAGE CIRCA 2019.

Also, the scene with Natalie shitting her brains out from some sort of flu is pretty solid. And kind of funny, since it’s related from the viewpoint of a few kids who think her expulsive ass is a ghost.

Guilty. Pleasure.

Also, spoiler alert, Sondra’s (Sandra’s? I’m not looking this up, sorry) husband kills himself and Natalie when, in a drunken moment that, honestly, reads a bit more like he’s tripping balls than drunk, he thinks she’s a porn star he’s seen on the Internets and decides to molest her. They crash into a lake and drown. That is this book. For 145 pages.

Which sounds pretty great? Except it’s a bit too telegraphed—Enzo kills a snail early on in sadistic fashion, just like he tries to kill everyone else—and the only real hook to keep the reader going is the idea that everyone is going to die. How will that happen?

On a scale of 1 to 10 I give this a score of NETFLIX TUESDAY. Not good enough to spend a Friday night on, but if you’re like, “hey, it’s Tuesday and I need to be entertained . . . The Laws of the Skies is streaming in book form. LET’S DO THIS.”

*

Instead of writing any more about The Laws of the Skies (which, again, isn’t bad, just not my favorite), I’m going to follow my initial lead and highlight each of the seven books written by women from Quebec that Rhonda Mullins has translated for Coach House. I’ve read none of these, and instead of pretending, I’m just going to go with posting the CHB copy and a comment/joke. (Including the Sam Miller inspired one alluded to above.)

But let’s start with Rhonda Mullins herself.

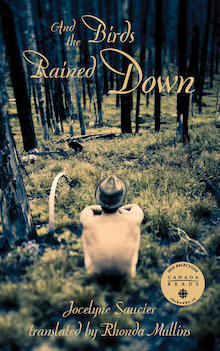

Rhonda Mullins is a writer and translator living in Montréal. She received the 2015 Governor General’s Literary Award for Twenty-One Cardinals, her translation of Jocelyne Saucier’s Les héritiers de la mine. And the Birds Rained Down, her translation of Jocelyne Saucier’s Il pleuvait des oiseaux, was a CBC Canada Reads Selection. It was also shortlisted for the Governor General’s Literary Award, as were her translations of Élise Turcotte’s Guyana and Hervé Fischer’s The Decline of the Hollywood Empire.

Since her Wikipedia page doesn’t include a total number of translated titles, I’m going to assume that one of these two statements are true: 1) She’s translated a ton of stuff since 2010 or 2) she has a notably high hit-rate for translating books that are finalists for major prizes.

Here’s a bit from an interview with Sara from Brazos:

Sara: I just wanted to start off by asking you about translating in general. We’re huge proponents of literature in translation, so I’m sure our customers would want to know what led you to the field of translation to begin with.

Rhonda Mullins: I kind of fell ass-backwards into it. I love hearing translators talk about how they got into it, because for so many of them it’s just a series of coincidences and circumstances. In my case, I was working as a marketing writer in tech, in an environment just before the bubble, so this is a very volatile environment. At some point, after the last company I was with closed down, I thought okay, enough of this, I’m going to work as a writer. I won’t lay myself off! I started writing, freelance, and somebody called me to do translation one day. So, financial motivation made me say yes. So I thought, I’d better study this. I went back to school and did a certificate in translation. From there, commercial to literary. It really has been . . . I feel very fortunate I really enjoy what I do and yet it wasn’t really by design.

Weirdly, this is the most normal story for translators. I know that I literally work for an institution that wants to help standardize the study of literary translation as a field and profession, but I kind of prefer this serendipitous way of becoming a translator. Not to mention, the best literary translators aren’t necessarily the ones who did classwork, but who worked with smart mentors and/or editors and have a knack for language that likely comes from reading a ton. By which I mean: COME TO THE U OF R FOR OUR MALTS PROGRAM. (Seriously, you should. Especially since you can get some academic chops while working with really, really great editors who know of translation.)

Anyway: Kudos to Rhonda Mullins for translating so many interesting sounding books, mostly for Coach House. Which, although Coach House is Toronto-based, is doing an amazing job bringing out Canadian authors in translation. There’s a healthy scene up there—one that we (meaning Americans) don’t pay enough attention to. And when we do, it’s all economically inflected in a weird, anti-meritocracy sort of way.

The Embalmer by Anne-Renée Caillé, translated from the French by RHONDA MULLINS

A small-town embalmer’s daughter lifts the shroud on the fascinating minutiae of dealing with the dead. Imagine rubbing shoulders with the dead for most of your life. As she picks the brain of her father for the most gruesome and thought-provoking secrets of his embalming career—from the drowned boy whose organs were eaten by eels to how to inject just the right amount of colour into a corpse’s skin for that blushing look—the narrator must look her parents’ deaths, and her relationship with them, straight in the eye.

Yeah, no, this isn’t a Chad book. The longer I can go without facing mortality, the better. I’m not sure how I watched Six Feet Under without losing my shit completely. I guess when you’re younger you really don’t count down the years . . . If I watch three TV shows a year, and live 20 more years, that’s 60 total shows before I never have a conscious thought again. So, should I watch Game of Thrones or The Good Place?

Speaking of losing one’s shit, I think I’m totally over this CBD craze. This might be a Rochester thing (?), but we don’t need every restaurant in town adding CBD to cocktails and vegan appetizers. I’d like my morning smoothie straight, thank you very much. Also? This feels like total bullshit. CBD feels like the Amway of anxiety treatments. If I’m gonna take the weed to feel better, I want to feel it, if you now what I’m saying. Go big or go home!

Little Beast by Julie Demers, translated by RHONDA MULLINS

Another book on my desk at work that I wish I had read!

It’s 1944, and a little village in rural Quebec sits quietly beside an aging mountain and an angry river. The air tastes of kelp, and the wind keeps knocking over the cross. Beside that river an eleven-year-old girl lives with her parents. Her mother is very sad, and her father has vanished because he can’t bear to look at his own daughter. You see, this little girl has suddenly sprouted a full beard.

And so her mother has shut the curtains and locked the girl inside to keep her safe from the townspeople, the Boots, who think there’s something wrong with a bearded little girl. And when they come for her, she escapes into the wintry night . . .

What was Quebec up to in 1944 as WWII was raging? Weird things involving kelp.

It’s going to take a few entires to make sense of my larger, weirder idea, so let’s start here.

In a normal publisher-agent/author transaction, the publisher tries to offer an amount of money that 1) won’t cripple them from making other deals, 2) is the lowest possible amount the author/agent will accept, and 3) has a positive sales + funding : advance + other variable costs + fixed costs ratio.

This is stupidly elementary. And no matter what anyone says in their mission, these things rule all indie and nonprofit presses. You don’t offer a $15,000 advance for a book that will cost $8,000 to have translated, $6,000 to print, when you have other fixed costs of $16,000 per book if you think that you’ll make, at most, $16,000 in sales (2,000 units at $16 a pop, disregarding distribution costs but including bookstore discounts) and $12,000 in other funding. Under those circumstances you’d lose $17,000.

Let’s put aside the idea that nonprofits serve a higher purpose for the moment. And let’s put aside the idea that presses have traditionally operated under a system by which 90% of their titles LOSE money, but one makes a TON. Instead let’s just let ride this simple economic truth for a second.

If you have to spend $16,000 (fixed costs) + $8,000 (translation)+ $X (advance) + $6,000 to print and that has to be < or = to $Y (sales) + $Z (funding) and you think the right side of the equation is $28,000 on average? . . . Ugh. Math.

Spoiler: Doesn’t work out! If $16,000 is fixed, as is $8,000, and $X (print costs) are $1.5/unit sold, and solve for Y (advance) with $16,000 in sales and $12,000 in funding? Then $24,000 + x + $3,500 = $28,000. Which means your advance is $500. And given a 7.5% royalty rate on list price of sales? You’ll owe more and lose money.

Which voices are still muffled because of these economics? WAY TOO MANY.

Suzanne by Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette, translated from the French by RHONDA MULLINS

If you’re a regular Three Percent (TP? 3%?) reader, you’ll know Suzanne. It’s come up like three four times already.

Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette never knew her mother’s mother. Curious to understand why her grandmother, Suzanne, a sometime painter and poet associated with Les Automatistes, a movement of dissident artists that included Paul-Émile Borduas, abandoned her husband and young family, Barbeau-Lavalette hired a private detective to piece together Suzanne’s life.

Suzanne, winner of the Prix des libraires du Québec and a bestseller in French, is a fictionalized account of Suzanne’s life over eighty-five years, from Montreal to New York to Brussels, from lover to lover, through an abortion, alcoholism, Buddhism, and an asylum. It takes readers through the Great Depression, Québec’s Quiet Revolution, women’s liberation, and the American civil rights movement, offering a portrait of a volatile, fascinating woman on the margins of history. And it’s a granddaughter’s search for a past for herself, for understanding and forgiveness.

This weekend, we KONMARI’D the crap out of our apartment. I have seen exactly zero episodes of her show and will, literally, never read her books, but the idea of throwing things away is logical and appealing. TMI here, but my mom (especially) is a “clean” hoarder (like, she keeps old toys and expired cans of beans, but animals don’t nest inside my childhood home; I didn’t grow up in a 100% full-on trash heap), and as a result, I tend to save things that I know are garbage, because why not.

I also used to own midwestern-sized houses, but post-divorce, that is much more difficult. (Less said here, the better. But there are stories and STORIES.)

Anyway, I threw away three garbage bags of clothes, and my daughter KONMARI’D like four bags of crap from her room, and another five from her brother’s. Best moment? Yelling KONMARI!!!!!!!! every time I threw something away. KONMARI! That piece of scrap paper is CANCELLED. De-cluttering is fun if you can gamify it with a meaningless slogan that you’re totally misapplying in a very ignorant way.

Guyana by Élise Tucotte, translated by RHONDA MULLINS

Nominated for the 2014 Governor General’s Literary Award for Translation All sorts of things can happen, no matter what road you take, and I never forget that. Death in particular can never be forgotten. Since Rudi’s death, I have tried to anticipate and dodge obstacles like an Olympic skier. My agile imagination glides between the little red flags with ease. Philippe’s imagination is both inï¬nite and inflexible. It’s a dangerous combination. He stays planted on the ground while looking down over reality. Between us, we do a good job of ï¬lling the realm of the possible. I figured I shouldn’t tell him the news: your hairdresser hanged herself in her salon. Ana and her son, Philippe, are grieving the loss of Philippe’s father when Philippe’s hairstylist, Kimi, dies in an apparent suicide. Driven by a force she doesn’t understand, Ana starts digging into Kimi’s past in Guyana in 1978, which leads to nested tales of north and south, past and present, and to the Jonestown Massacre. A stunning translation of a masterpiece by one of Quebec’s most important novelists.

Winner of the 2015 Governor General’s Literary Award for French-to-English Translation

An abandoned mine. A large family driven by honour. And a source of pain, buried deep in the ground.

We’re nothing like other families. We are self-made. We are an essence unto ourselves, unique and dissonant, the only members of our species. Livers of humdrum lives who flitted around us got their wings burned. We’re not mean, but we can bare our teeth. People didn’t hang around when a band of Cardinals made its presence known.

With twenty-one kids, the Cardinal family is a force of nature. And now, after not being in the same room for decades, they’re congregating to celebrate their father, a prospector who discovered the zinc mine their now-deserted hometown in northern Quebec was built around. But as the siblings tell the tales of their feral childhood, we discover that Angèle, the only Cardinal with a penchant for happiness, has gone missing—although everyone has pretended not to notice for years. Why the silence? What secrets does the mine hold?

A 15th-century portrait painter, grieving the sudden death of his lover, takes refuge at the monastery at Mont Saint-Michel, an island off the coast of France. He haunts the halls until a monk assigns him the task of copying a manuscript—though he is illiterate. His work slowly heals him and continues the tradition that had, centuries earlier, grown the monastery’s library into a beautiful city of books, all under the shadow of the invention of the printing press.

$16,000 (fixed costs) + $8,000 (translation)+ $X (advance) + $1.5 per unit sold and that has to be < or = to $Y (sales) + $Z (funding)

$16,000 (fixed costs) + $8,000 (translation)+ $X (advance) + $1.5 per unit sold and that has to be < or = to $Y (sales) + $16,000 (funding)

A CBC Canada Reads 2015 Selection!Finalist for the 2013 Governor General’s Literary Award for French-to-English TranslationDeep in a Northern Ontario forest live Tom and Charlie, two octogenarians determined to live out the rest of their lives on their own terms: free of all ties and responsibilities, their only connection to civilization two pot farmers who bring them whatever they can’t eke out for themselves. But their solitude is disrupted by the arrival of two women. The first is a photographer searching for survivors of a series of catastrophic fires nearly a century earlier; the second is an elderly escapee from a psychiatric institution. The little hideaway in the woods will never be the same. Originally published in French, And the Birds Rained Down, the recipient of several prestigious prizes, including the Prix de Cinq Continents de la Francophonie, is a haunting meditation on aging and self-determination.

Leave a Reply