“The Faerie Devouring” by Catherine Lalond [Quebec Literature from P.T. Smith]

Before starting this month’s focus on Quebec literature, I asked P.T. Smith to recommend a few books for me to read, since he’s one of the few Americans I know who has read a lot of Quebec literature. But rather than hoard these recommendations or write silly things about them, we decided it would be best if P.T. wrote weekly posts throughout February covering some of his favorite works of Quebec literature ever. You can find his earlier entries here.

This is my last post for Quebec month at Three Percent. My last Tuesday spending the day on and off writing about a book from Quebec, walking the dog, reading something else, editing at the bar, and going to bed. It’s not a bad Tuesday. I’ll miss Quebec month. I’m also going to end it on a different note. When Chad asked me for recommendations, I gave him three classics, and then the most recent book from the province I’d read. So it’s not a classic. It’s only from 2017 and the translation is from last year. It’s not even a recent read for me anymore. There’s a couple between Chad’s ask and now. But plans can be nice, and I’m sticking with this one. So, what do I have to say about Oana Avasilichioaei’s translation of Catherine Lalond’s The Faerie Devouring? Plenty, because I both love and I’m lost in it. Love and lost? That might be how I prefer to be.

This is my last post for Quebec month at Three Percent. My last Tuesday spending the day on and off writing about a book from Quebec, walking the dog, reading something else, editing at the bar, and going to bed. It’s not a bad Tuesday. I’ll miss Quebec month. I’m also going to end it on a different note. When Chad asked me for recommendations, I gave him three classics, and then the most recent book from the province I’d read. So it’s not a classic. It’s only from 2017 and the translation is from last year. It’s not even a recent read for me anymore. There’s a couple between Chad’s ask and now. But plans can be nice, and I’m sticking with this one. So, what do I have to say about Oana Avasilichioaei’s translation of Catherine Lalond’s The Faerie Devouring? Plenty, because I both love and I’m lost in it. Love and lost? That might be how I prefer to be.

The original was nominated for the Governor General’s, one of the highest awards in Canadian literature. It was nominated in the poetry category, even though the publisher, Le Quartanier, lists it as a novel, and Book*hug lists their English edition as a novel. The second you open it up, it makes sense why some call it poetry. Most pages have a single block of text, with plenty of white space on all sides. Occasionally, a line breaks off into emptiness before picking up again, that white expanse between asking you to make something of it. Some pages only have a single sentence, or a few words. The only time that the text runs from the top of the page to the bottom, it’s a speech that looks . . . well, a hell of a lot like poetry.

I’m not interested in identifying what label is most useful or most accurate, but I sure am interested in letting you know it playfully, comfortably, floats between identities. This fluidity isn’t just because Lalonde is skillful enough to manage the flow, but it’s the essence of the book, of the sprite at its heart. Most importantly, it means if you want to recommend it to someone who likes novels, tell them it’s a novel, if they prefer poetry, tell them it’s poetry, and if it’s someone who goes on and on about hybrid forms, just put it in their mouth. It’s a slim book, they’ll be fine.

I’m not interested in identifying what label is most useful or most accurate, but I sure am interested in letting you know it playfully, comfortably, floats between identities. This fluidity isn’t just because Lalonde is skillful enough to manage the flow, but it’s the essence of the book, of the sprite at its heart. Most importantly, it means if you want to recommend it to someone who likes novels, tell them it’s a novel, if they prefer poetry, tell them it’s poetry, and if it’s someone who goes on and on about hybrid forms, just put it in their mouth. It’s a slim book, they’ll be fine.

I wanted to review this when it came out, but never managed it. I haven’t been writing much, especially not straightforward, formal reviews where I lay out a way to read the book, some flaws and some failures, make sure to land a not-completely-generic point about the translation, have a conclusion, and edit tightly. I haven’t been all that interested in reading things before they come out to make sure that review is ready to run right around release date. Those are the non-specific reasons I didn’t write about The Faerie Devouring before this. There are loads of excuses particular to this book, coming from its qualities and my inadequacies.

I noted that it’s close to prose poetry. This guy has no idea how to read poetry. See any and all of Chad’s posts on his own failings with poetry. It’s me. More important than that though, Faerie is a painful, wrenching, violent (not in the way you may think), feminine book. And I hesitate to even call it feminine, because it’s not that in any older, traditional meaning of the word, but I don’t know what else to call it. I don’t think Lalonde would disagree, I’m not sure anyone would . . . but I’m a dude trying to talk about a very poetic book that is about a wild, wild, visceral, honest expression of femininity, one that is among many things, a rage against the identity that culture puts on femininity, and eventually an embrace of womanhood specific to one woman. So what in the fuck do I get to write about that?

Okay: plot. A daughter is born. Mother dies in childbirth. Her family is her grandmother and five boys: “John-Jude the adopted eldest, JJ her pride and joy; the brat Peter-Joseph, JJ’s son, JJ, the precocious papa; James the mongoloid, adopted with; her own Luke; and the late-born Matthew.” The novel opens with her birth, “After the clamour of flesh, after the bloody harvest of the mound—liver, spleen, entrails, adorable arteries—the little mound more torn out than pushed, uprooted by the neighbour’s skilled hands.” The first section, the birth, with extended descriptions like that one, faces, bodies, builds up to five words Gramma says, five words spoken after it’s all over, “Fuck. It’s a girl.”

It’s a curse to be a girl, isn’t it? It’s a condemnation to a certain existence. This is a bodily book, relentlessly physical and graphic, and doesn’t a woman’s body come with punishment for being a woman? That’s not rhetorical. Isn’t that a thing many women feel? God I’m out of my element.

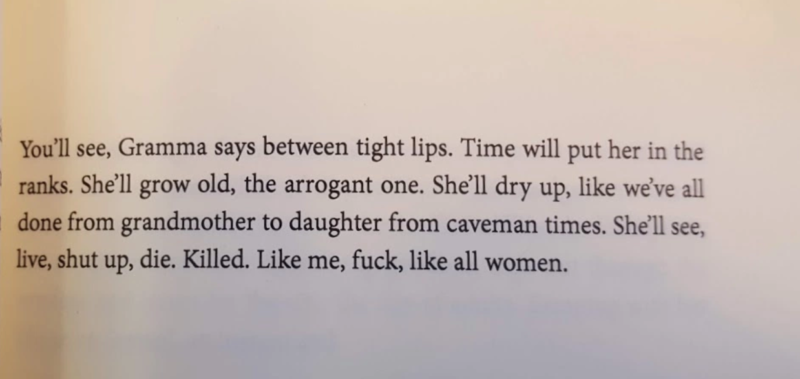

I’m convinced I’m not making it up by this though:

Gramma’s waiting for the prophesy, waiting to see the sprite join the military ranks of flesh and fresh fillies: waiting for her to return dried out, old; for her to return erased if not dead, like all women: of shame, rape, anemia, famine, TB, Pythia, family, restraint, embarrassment, hate, silence, dead from stitching, breastfeeding, ass-wiping, dead at the bottom of the lake, foot caught in the trap, ring on the finger—living dead like all the others all the same. Dead from living. Like all women.

Lalonde isn’t always that direct. Instead, like the title suggests, she takes the language of the fairy tale. But does she make it hers. Early on, the girl’s name is basically lost: “even lets her suck cow milk off her callused fingers. Nipples are for the rich. Rock-a-bye baby slurps the taste of hair dung and soil, then gets the runs of jaundice. Three times she gets it, and the sprite toughs it out. The sprite—the name sticks.”

I’ll come back to this novel as a fairy tale, but as much as this straddles, or moves between, prose and poetry, it does the same for other boundaries between genres. The family lives a rural life, seemingly devoid of any organization except the wrath of Gramma: school, work, law, hardly exist. In it’s own distinct way, the book is also an idyll:

It drags on, disharmony for a quackgrass orchestra, while the rest work on napping or rock skipping. The sprite loses interest, fidgets, knots, braids, plaits fragile grass effigies, amulets with dandelion faces and green-wheat arms. The redhead catches ladybugs for her, squishing them to make eyes.

It’s a vicious and nasty book, and god I love it.

Anything I could say about Faerie Devouring is better served by the book itself.

Best description of Gramma? “Gramma slurps with pleasure when it’s Ass Lake chowder night, and in her devouring, her lips soften, her face loses its ravenous wicked faerie godmother look.” That’s an entire page, by the way.

What does a happy family look like? “The six-headed monster scampers around, turns into a tornado, a wild herd, a caterpillar of linked legs: the spritely papoose bareback on the mongoloid, the brat behind putting on airs, the older ones jumping over the hurdle, turning a sharp corner.”

It’s a coming-of-age novel: “She’s thirteen, the sprite, and her first rootword rings clear, her first word, her true love. No. No. Who will be will know, who will know will see and what I’ll be will wart.”

Do I need to quote anything else to show that this is an insane, unique book? That to write it takes a passionate author, wild, brilliant, and free, and that the translator must be all those things too?

It’s almost dull that I like this book as much as I do, cause I’m a sucker. I’m a sucker for books as visceral as this one. Literary work that has piss, shit, vomit, sex, masturbation, and blood? I’m almost certainly game. An all-time favorite quote for me is from Zündel’s Exit: “That’s life, my life anyway, chains, falls, scrapes, and I’m afraid I pissed myself as well.” But often, it’s old hat. Here, it’s new. It’s a woman’s body and mind that has all this going on. It’s different. #readwomen. Not because it’s a moral good, but because I don’t want the same thing again and again and again.

It’s almost dull that I like this book as much as I do, cause I’m a sucker. I’m a sucker for books as visceral as this one. Literary work that has piss, shit, vomit, sex, masturbation, and blood? I’m almost certainly game. An all-time favorite quote for me is from Zündel’s Exit: “That’s life, my life anyway, chains, falls, scrapes, and I’m afraid I pissed myself as well.” But often, it’s old hat. Here, it’s new. It’s a woman’s body and mind that has all this going on. It’s different. #readwomen. Not because it’s a moral good, but because I don’t want the same thing again and again and again.

“She pisses standing up to see herself flow, yellow streams her odour has changed.” “And fucking? Another story. A story of no more rump or gristle, only shitting or finding something to feed the mouth and the belly. The sprite comes, makes them come and returns to the chaos, like backwash.” “the sprite, force-fed with memories, the return of sensations, masturbates frantically all at once, as quietly as possible, standing up against the closed door of the boy’s room, comes immediately, comes with the solar speed of the solitary orgasm that remains one of her great, great secrets.”

Masturbation seems like a fine place to end. I could go on. But I can’t. No bit does it justice. Fragments entice, but the whole is another thing. The whole is something that as a dude, I’m not sure I can grasp, but I can work towards it. Something in my will fail Faerie Devouring. I’m okay with that. I can love it anyway. I do. You will? If you do, if you don’t, I want to hear from you. This is chick lit for the insane, intense, intelligent, angry, raging against the world literary crowd? I might get yelled at for that, I think, but in a good way.

My final other recommendations. For another book I couldn’t grasp because it’s abstracted out of my reach, another book that is strange and metaphorical (it’s set in a giant structure where families live in cells?) but also grounded and physical and intense: Karoline Georges’s Under the Stone. Hey! Lalonde blurbed it. It’s translated by Jacob Homel, which brings me to How to Make Love to a Negro Without Getting Tired, Dany LaFerrière’s novel, translated by David Homel, Jacob’s father. I haven’t read it yet, not even started it, but it’s next for me. He’s Haitian-Canadian. Or Haitian-Quebecois. Cultures within cultures. I’m eager to dive in.

My final other recommendations. For another book I couldn’t grasp because it’s abstracted out of my reach, another book that is strange and metaphorical (it’s set in a giant structure where families live in cells?) but also grounded and physical and intense: Karoline Georges’s Under the Stone. Hey! Lalonde blurbed it. It’s translated by Jacob Homel, which brings me to How to Make Love to a Negro Without Getting Tired, Dany LaFerrière’s novel, translated by David Homel, Jacob’s father. I haven’t read it yet, not even started it, but it’s next for me. He’s Haitian-Canadian. Or Haitian-Quebecois. Cultures within cultures. I’m eager to dive in.

Leave a Reply