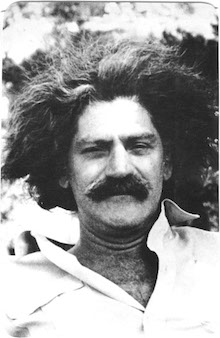

Jakov Lind [Open Letter Author of the Month]

The selection of Jakov Lind as our “Author of the Month” will make even more sense after Monday’s post, but after telling my class about Landscape in Concrete on Tuesday, I really wanted to revisit his books—and wanted to convince all of you to join in!

As always, for all this month, you can get 30% off of both of his books (Ergo and Landscape in Concrete) by using LIND at checkout.

Next week we’ll run a long post (and excerpt) about Landscape in Concrete and one about Ergo the Friday after that, so for today, I just want to quote (extensively) from his fascinating bio. If you haven’t heard of Lind before, you’re in for a ride.

Jakov Lind, one of the greatest of post-war writers, who bore witness through his darkly surreal and imaginative tales to the madness of our time, was born Heinz Landwirth on February 13, 1927 in Vienna. On March 13th, 1938 the Nazis marched into Austria. “The war against the Jews began practically the next morning”, wrote Lind. “By Saturday all of Vienna was one big swastika.” It was no longer safe to be a Jew in Austria. In December of 1938 Lind and his sisters were placed on a kindertransport (children’s train) bound for Holland. He was eleven years old.

In as yet unoccupied Holland, Lind learned fluent Dutch in a matter of weeks. He lived in a Zionist children’s home near the Hague and was later taken in by a Dutch Jewish family. In 1941, he found himself in a Zionist training camp where young “pioneers” received agricultural training to prepare for emigration to Palestine (already forbidden by the Nazi authorities.) After witnessing the first mass roundup of Jews in 1943, Lind made the decision to go underground in June 1943 and obtained false identity papers in the name of Jan Gerrit Overbeek, Dutch laborer. On the way to get his papers, Lind writes: “I pinned my Nazi badge up front, put on my grey hat with the brim down, tied a black tie over my dark grey shirt, and looked like a Nazi home from a spell of duty. I put on a fierce look, and left for Line 3 . . . Office workers and labourers on the streetcar moved away from me . . .”

Several months later Lind found work on a river barge transporting goods between Holland and Germany, “sailing under a false self”, he later wrote. But when the Allied bombing attacks began on the industrial cities along the Rhine, it was time to get off the river. It was then that a miracle, as he referred to it, brought him a job as a courier for the German Air Ministry. [. . .]

In 1954 Lind landed in Dover, made his way to London and decided to stay. There he married Faith Henry and had a son, Simon, and a daughter, Oona. Settled in London, he began work on a collection of short stories. Eine Seele aus Holz (Soul of Wood), published in Germany in 1962, was proclaimed a masterpiece, became an immediate literary phenomenon, and was translated into fourteen languages. As one critic wrote: “Lind’s general theme is the destruction of European Jewry . . . He treats it with a kind of broad gallows humor, utterly grotesque and fascinating . . .”

Compared to Kafka, Grass and Gogol, Jakov Lind became an international literary star overnight. But he did not want to be a German writer. It felt like betrayal to write in German, his mother tongue which had so recently been put to such murderous use.

Lind’s second novel, Landscape in Concrete was published in 1963. Ergo, a novel, came out in 1968 and became a successful play produced by Joseph Papp in New York. In 1965 and 1968 The Silver Foxes Are Dead and Other Plays were published and performed as radio plays in Germany. And then, encouraged by his publisher, a major shift occurred. Lind wrote his first book in English, Counting My Steps (1969), an autobiography of his childhood in Vienna and his war years in the Netherlands and Germany. This was the beginning of Lind’s distancing himself from his mother tongue and the pain and ambivalence of writing in German. But it also distanced him from his roots. “Madder than anything”, he wrote, “was to think I could ever unlearn sounds I knew by heart and kidneys and replace them with other and better sounds.”

Lind was to write three more autobiographies: Numbers (1972) on his wanderings across Europe after the war; the Trip to Jerusalem (1973); and Crossing: The Discovery of Two Islands (1991) about his arrival in England and the years in London and New York. In the 1980’s Lind published a novel, Travels to the Enu: The Story of a Shipwreck (1982), The Stove (1983), a series of short parables, and The Inventor (1987), an epistolary novel, all of them written in English and translated into many languages. [. . .]

On February 16, 2007, Jakov Lind, one of the major literary figures of our time, died in London of heart failure. He was 80 years old.

Here’s a link to his full bibliography, and if you’re intrigued, I highly recommend staring with Landscape in Concrete, translated from the German by Ralph Manheim . . . or his translation of Ergo. And remember: use LIND and get 30% off!

Leave a Reply