NYRB Classics: Some Stats [Strategies for Publishers]

This month, I’m going to switch things up a bit. Initially, I was going to leave Canada behind and focus on one single book: Uwe Johnson’s Anniversaries. But, well, this is 1,600 pages long, and I have to proof a couple things this month, and reread some books for my class, and go to AWP, and catch up on Deadly Class and Brockmire, AND BASEBALL STARTS IN 25 DAYS.

Instead, I’m going to read all four volumes of Anniversaries over the next four months, and include comments about each of the volumes in some post—even though future months will have non-German foci. But for March, rather than trying to center all of the posts around a single language or region or book, we’re going to make them all about a given press: NYRB Classics, one of the most beloved and respected publishing houses in America.

There’s no need to explain NYRB here—every single person reading this blog has at least one, or twenty, of their books—but given their scope, I do have to rein things in a bit, and pick a specific angle to focus on . . . Which is even complicated when you’re just talking about the translated titles that they’ve done!

So here’s the plan: This week I’ll just run some stats on NYRB from the Translation Database and highlight some of their forthcoming books. Next week I’ll write about the first volume of Anniversaries and the retranslations & reprints NYRB has done. Then, I’ll round things out with a post about some of the original titles in translations they’ve done.

(And hopefully I can get some interviews and/or bonus episodes of the Three Percent Podcast set up this month as well. I know I’m moments away from this turning into a crutch, but I’m not as organized as I hoped to be with rebuilding my data. Next week is spring break though, and by mid-March, I will be solid and back on track.)

And then, for the last Monday of March (the 25th), I’m going to kick off the Marie-Claire Blais project I mentioned in the last post, by writing about These Festive Nights. Like with Anniversaries, it’s a bit too much to read all the books in her Soifs series in a month (even if only five of the ten books have been translated so far), and breaking it up over a longer period can only help convince some people to give her a try.

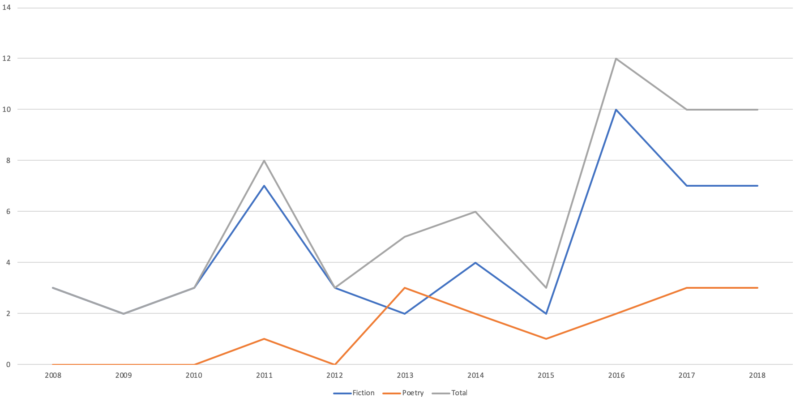

This chart really doesn’t look like much at first glance. For any number of reasons. First off, it’s a year-by-year chart (something I’m sure I’ll comment on more below), but it’s also only capturing the books that NYRB has published that had never before appeared in the U.S. Not in any translation—abridged or incomplete, flawed or held in the highest regard.

What makes NYRB fascinating—and tricky to write about for these post—is that their international lit program is a portion of what they do, and within that portion they publish: 1) new translations that have appeared nowhere before (NYRB brings the book fully into existence in English); 2) translations that previously only existed in the UK (NYRB brings the book to an American audience); 3) restoring translations that were incomplete for political or publishing reasons (Anniversaries, for example, but also Berlin Alexanderplatz and others); and 4) reissuing translations that have fallen out of print (the Raymond Queneau books, or, although it’s not in translation, the recent Henry Green project).

The chart above? That’s only capturing #1 of the four categories listed above, and is thus a very slanted picture of NYRB books as a whole.

Which is fine! The Translation Database was designed to capture one thing—new voices and books available to American readers for the first time—which it does remarkably well. (BRAGGING.) I’ve thought about expanding it in various ways, and have (see addition of nonfiction and children’s books, which are being added to currently, and about which more info will be available in the not-too-distant future), but not beyond this one fundamental criterion. Including all retranslations and reprints does add to the picture of international publishing as a whole, but I’m not 100% sure it’s the responsibility of the Translation Database (a.k.a. ME) to do that. I started this as a research project in 2008 to answer some specific questions, and if your question isn’t being captured in its entirety (yet?), I’m sorry? 🤷

What that doesn’t mean is that the data gathered in the Translation Database, or analyzed here or in articles for PW or wherever is “inaccurate” or “dismissable.” Just because some facts aren’t what you wish they were doesn’t mean they’re wrong. Hunter Pence still isn’t a HOF caliber player. (Deep cut for long-time fans there.) The Database tracks this particular subset of published books really well. Because I spend half my free time sweating over iPage and 100+ catalogs and Edelweiss and all the books that are mailed to our offices. If you think something’s missing, we have a form for that! (Yes, I will clear it out soon. It’s jammed up with inaccurately entered kids’ books right now, which is a story for the next podcast.)

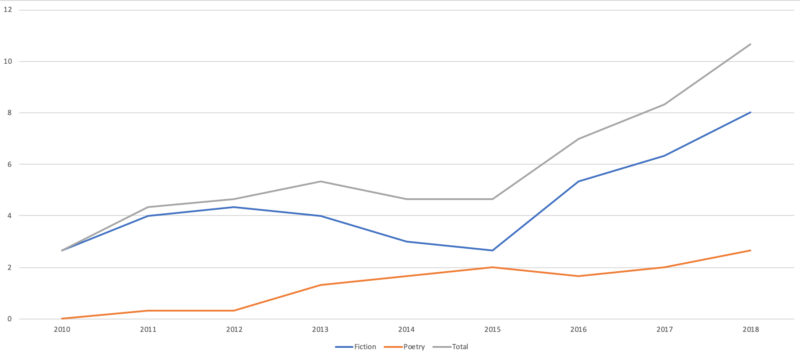

For the data and graph nerds (here! here!), here’s a three-year rolling average of NYRB’s original translations. They go up!

*

Which brings me to the “back-up feature” of March’s posts: Business strategies for various stakeholders in the translation community.

This idea is never far from my thoughts (see last year’s post about treating authors like soccer players and buying/selling their careers), but I’ve been listening to William Poundstone’s Fortune’s Formula: The Untold Story of the Scientific Betting System that Beat the Casinos and Wall Street about the Kelly Criterion (a way of maximizing profits and avoiding gambler’s ruin when you can calculate the odds of any given transaction), Claude Shannon and information theory, blackjack and roulette, the stock market, RICO, and much more.

The idea that there’s a “most efficient way of gambling” really hits home with me, given how much of publishing is based in calculated luck. In gaining edge and doubling d0wn when it’s most advantageous. Given how much of publishing success is based in information exchange already, “insider trading,” etc., there is likely a mathematical way to figure out when to bet (a.k.a., advance and invest in marketing) what on which books to maximize your return over the course of an infinite amount of time. That might not be your goal—obviously need to talk about utility at some point—but it seems calculable.

(Why doesn’t publishing hire anyone to be a wide-ranging analyst to ask questions and mine what data are available? Maybe they do??? That’s hard to imagine though, given that so many big time editors reject books based on profit-and-loss statements that say a book is “neither literary enough, nor sci-fi enough to work.” That reeks of “gut instinct” and an unhealthy obsession with pigeonholes and faux predictability.)

I have a doozy planned for next week, but rather than start this mini-series from the perspective of a hypothetical newbie translator, it seems more logical to open up from the perspective I spend the most time thinking about.

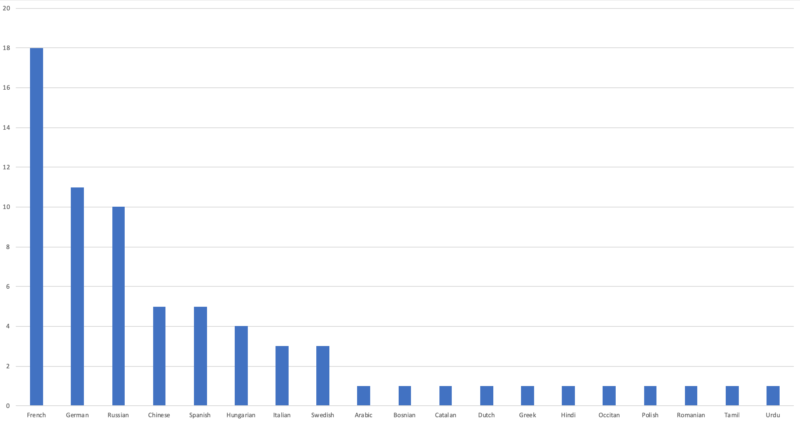

Principle #1: Publish from languages that are popular, unless there’s a significant edge between customer interest and book availability.

Rule number one of translation publishing is that your press “wants to be as diverse as possible, covering all the globe’s languages and cultures.”

Rule number two is that it’s most profitable to do books from Spanish, German, and French, since readers are familiar with those cultures and are, for worse, less likely to go all in (en masse, as a group that will make a book popular) when it’s from a more obscure language. Like, let’s say, Latvian.

But look at what NYRB tapped into . . . Russian and Chinese. Languages with huge reading populations, long histories, and fewer titles available in English than the Big Three. SMART.

Well that’s definitely not 2019 . . .

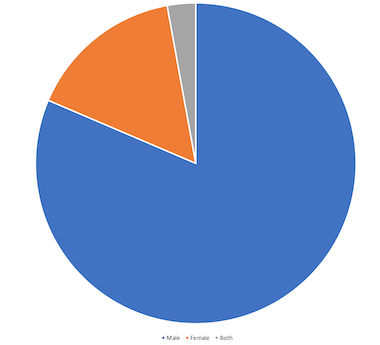

Principle #2: Play the long game and assume that as long as the patriarchy assumes the most “classic” authors are men; Don’t worry about it, but never sleep OK again.

I do not believe in that. TBH, I might not believe in any of these statements. But emotion and hope is different from truth and data.

Of our top 15 best-selling books (as of November 2018, and yes, I know), only THREE are written by women. Is Open Letter 50%-50% in gender equality? No! But we’re better than that above. But. But. But. The books we do by women do not sell. I’ll run the numbers for you as soon as I catch up on rebuilding sales reports . . . (I found a spreadsheet from April 2017 that I’m updating. Also, why does the universe hate me so much?)

Rock, Paper, Scissors and Other Stories by Maxim Osipov, preface by Svetlana Alexievich, edited by Boris Dralyuk, translated from the Russian by Boris Dralyuk, Alex Fleming, and Anne Marie Jackson

Principle #3: Get a lot of people involved.

This is especially true when you want to include booksellers, reviewers, or other tastemakers. Adding a well-known bookseller to the cover of your publication shifts the odds in your favor a little bit.

Same for LARB editors and Nobel Prize winners!

(I still don’t know how to process the Alexievich Nobel given how much struggle it was for me, personally, to get Voices from Chernobyl published as a hardcover at Dalkey, then to sell the paperback rights to Picador in the largest sub-rights deal in Dalkey history, and then to be not at all able to participate in the celebration of her Nobel. Am I bitter? I try hard not to be, but I am. Full stop.)

A Dictionary of Symbols by Juan Eduardo Cirlot, introduction by Philip Pullman, translated from the Spanish by Jack Sage and Valerie Miles, epilogue by Victoria Cirlot

Principle #4: All Intellectual Property is more valuable as an HBO series than as a book.

I’ve said this a million times, but books are so small (sales and money-wise) in impact compared to most other media. 45 million (?) Netflix subscribers saw Bird Box, which, FYI, SUCKS, but like 40,000 people in America have read a book by Bolaño?

GO FOR THE HOLLYWOOD MONEY. IT WILL SHIFT COPIES.

(For anyone who didn’t make all those connections, Philip Pullman, friend of the recently deceased Nicholas Mosley, who was amazing and whom I miss and think about a lot, is the His Dark Materials trilogy author who has had a movie made of Golden Compass and has a new HBO series coming out.)

Fragments of an Infinite Memory by Maël Renouard, translated from the French by Peter Behrman de Sinety

Principle #4: Be cool, be a Brand; No, not a “Brand,” but a “brand.”

Leave a Reply