“Book of Minutes” by Gemma Gorga [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards.

Nancy Naomi Carlson is a poet, translator, and editor, whose latest book was called “new & noteworthy” by the New York Times. Recipient of two NEA literature translation grants and a finalist for the BTBA and the CLMP Firecracker Poetry Award, she’s been decorated with the French Academic Palms. Her work has appeared in APR, The Georgia Review, The Paris Review, and Poetry.

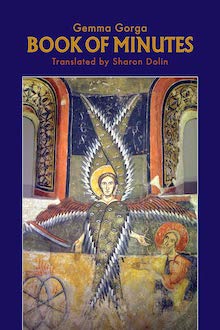

Book of Minutes by Gemma Gorga, translated from Catalan by Sharon Dolin (Oberlin College Press)

Before Covid-19, reading, for me, was a guilty pleasure, squeezed between a day job and the rest of my life, some of which required me to be out and about in the world, when not working countless hours writing and translating alone in my study, with a sleeping schnoodle at my feet. Now it seems I have been the recipient of countless hours in which much of my contact with the outside world is through books. And what better choice, when housebound, than a poetry book seeped in the domestic, that takes us beyond our own walls to as far as we might travel—even to the metaphysical world. Such a book is Gemma Gorga’s Book of Minutes, the author’s first volume of work to be translated into English. And what a beautiful translation it is, translated by Sharon Dolin, an accomplished and critically acclaimed poet in her own right, and awarded a PEN/Heim Translation Fund grant in support of this project.

Written in the great tradition of prose poems (think Baudelaire, think René Char, think Russell Edson), these sixty polished gems are quirky, at times surreal, lushly layered in sound, and infused with wisdom, poem after poem. The poems here are in conversation with one another, each like the old mountain house Gorga describes, “. . . at the same time, so many houses,” resembling “a magic box lined with mirrors: you open it and from inside, out comes another; you open it and from inside, out comes another. Perhaps that is why they say houses are like people.” Unforgettable images romp through these pages: canaries chirping out of tune; acrobats made entirely of glass; wolves in baskets, rather than lurking in the thicket’s lower branches, and Nazarene-colored eyes.

These poems move me, with their universal and inescapable truths, as well as the deeply personal, made more urgent by these days of endless quarantine. Here is the book’s first poem in its entirety, so apt for today’s common reality:

We sat around the table. Sometimes there were thirteen of

us sharing the light breaking through our fingers, as thin as

unleavened bread. Sometimes we were only two, possibly

you and I, or just our hungry shadows. Sometimes a single

person sat with fingers probing the wood, like someone

seeking the warm bowl of foaming light.

Until one day we found out about death, almost by chance,

as if it were a game: every evening there were fewer chairs

arranged around that table. No matter how tired and old,

we still ran to make sure of a seat, to seize from life the

last morsel of light.

Gorga’s lyrical aphoristic bursts are compelling, and sometimes dark: “Happiness resembles a monosyllable…due to the brevity with which it visits our mouth”; “In the center of the rose it is always night.” Yet as long as there is light, there is hope. Similarly, as long as there are words, there is hope, as in the book’s final poem: “The mouth is small, depending upon the word. Silence,/however, is immense, like an old homestead: within it every-/thing fits, and everything is lost.”

Leave a Reply