“Welcome to America” by Linda Boström Knausgård [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards.

Katarzyna (Kasia) Bartoszyńska is a former BTBA judge (2018 and 2017), a translator (from Polish to English), and an academic (at Monmouth College, and starting this Fall, at Ithaca College). She is currently translating two books, one by Zygmunt Bauman, and another by Dariusz Brzeziński, and recently completed her own book, on theories of the novel, to be published by Johns Hopkins UP.

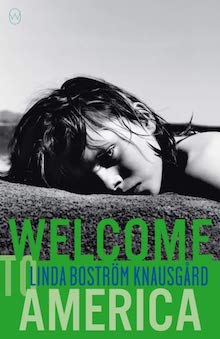

Welcome to America by Linda Boström Knausgård, translated from the Swedish by Martin Aitken (World Editions)

In a recent study of the novel as a genre, Wendy Anne Lee has argued that, rather than being obsessed with plumbing the depths of characters’ hearts and minds, the novel form is fascinated, and spurred into action, by insensible characters, people like Bartleby the Scrivener, who remain impassive, unfeeling, impenetrable. It is these characters, she says, who allow us to see that emotion is rooted in responsiveness, which in turn produces action: ‘moved’ bodies, moving. The insensible throws a wrench in the works, allowing us to see the animating mechanism: by refusing to engage, an unfeeling figure drives other characters to a frenzy, setting the story into motion.

Lee is writing about eighteenth-century fiction, but I thought about her argument often as I read Linda Boström Knausgård’s astonishingly absorbing Welcome to America, the story of an 11-year old girl who refuses to speak. One of the great satisfactions of this slender text is that it isn’t structured around the idea of this refusal as a problem: we are not seeking out the reason (though we get some hints along the way), or awaiting a resolution in the form of a return to communication. Rather, we witness the effects: the responses of her mother, brother, teachers, which delineate the delicate fault lines of power, loyalty, and love running through this family. Along the way, too, we hear about their past, noticing all that has been unsaid, the questions “hanging unuttered” — and unanswered (36). So the novel makes us think about what holds families together, and what breaks them apart, and the various forms of control we have over ourselves and others.

What was so consistently surprising to me, as I read, was that I couldn’t stop reading; that although this is a story with hardly any discernible plot, at least in the traditional sense of the word, it is absolutely riveting. Partly, of course, this is the power of the prose. Martin Aitken, who also translated that other Knausgård, does a wonderful job (though I was slightly distracted, at times, by what seemed like a clash of different Englishes, sometimes British, sometimes perhaps not – do Mum and bonkers belong to the same geographic register?). I especially loved the way he managed to retain a sentence structure and word order that are atypical of English, without ever making it seem awkward of confusing. But the book’s power also lies in the brilliant way that the story shifts and weaves, between past and present, action and reflection, following one thread for a few pages and then introducing an entirely new line of thought (what does it mean to grow up?) that both builds on and reconfigures everything you’d been tracking before, shining a new light.

It’s a quick read, but a fascinating one—richly deserving of the prize.

Leave a Reply