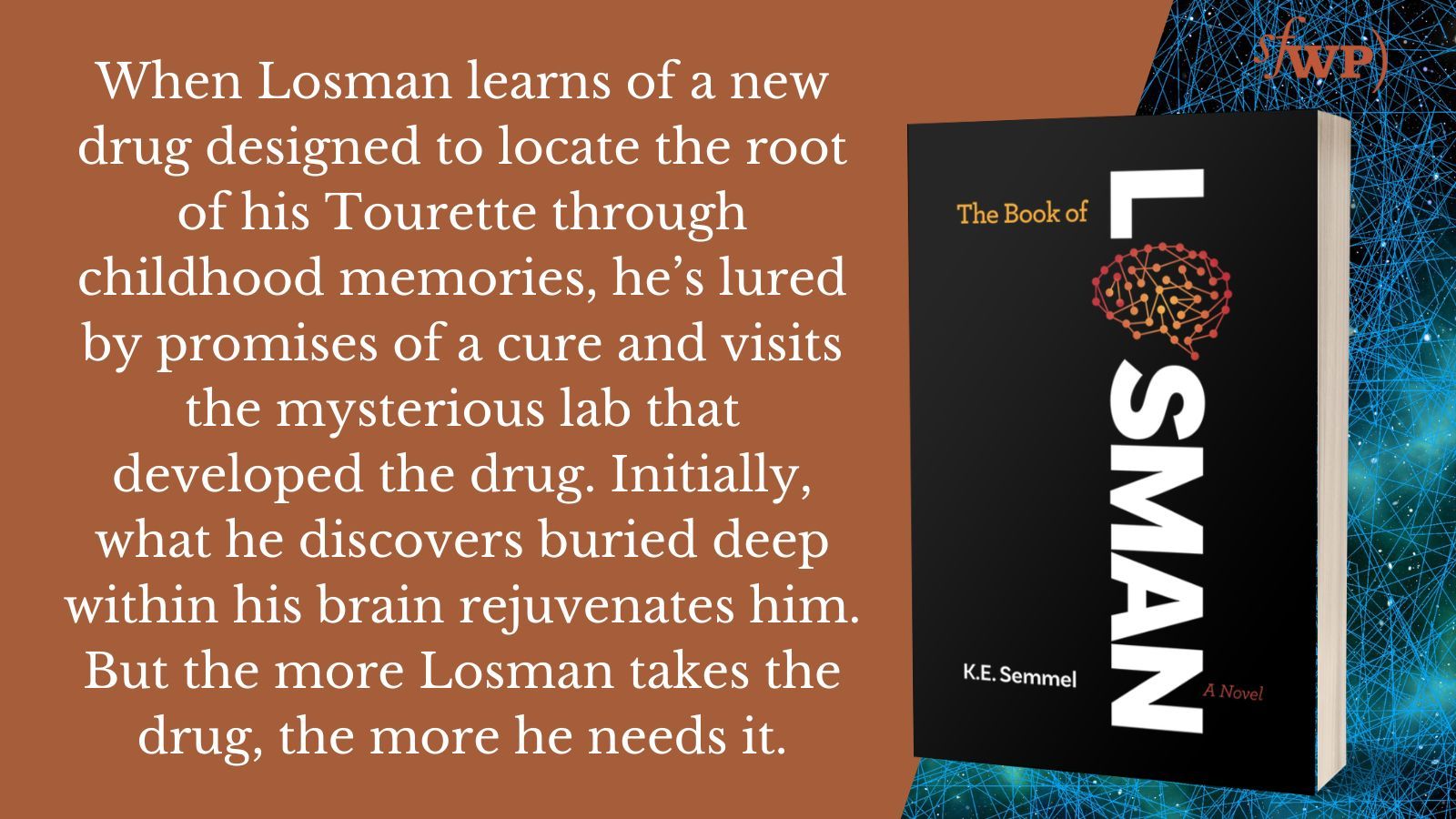

Three Percent #193: K.E. Semmel, “Book of Losman”

On this week's podcast, K.E. Semmel—translator from the Danish and author of Book of Losman—discusses his debut novel, life as a ...

Dubravka Ugresic’s “A Muzzle for Witches”

To mark the release of Dubravka Ugresic's final book, A Muzzle for Witches (translated from the Croatian by Ellen ...

Three Percent #191: Pilar Adón, “Of Beasts and Fowls”

In this special edition of the podcast, Chad talks with Pilar Adón about the forthcoming Of Beasts and Fowls (translated by Katie ...

Pilar Adón Reading Tour!!

This September, Pilar Adón—author of Of Beasts and Fowls (translated by Katie Whittemore), winner of Spain's Premio Nacional de Narrativa last year—will embark on a five-city, six-stop tour hitting several of the best indie bookshops in America, and sharing this incredibly beautiful, compelling ...

>

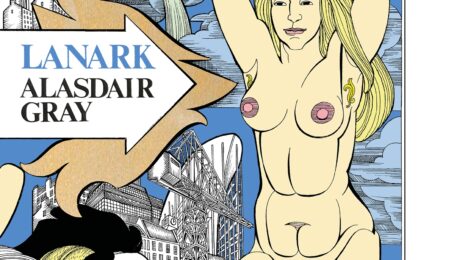

TMR 23.9: “My Maps Are Out of Date” [Lanark]

It all gets wrapped up with a "Catastrophe,." "Explanation," an "End," and a "Tailpiece." Chad, Brian, and Kaija discuss global capitalism, the fight for love and the be human, AI, the Bardo, and much more on this final episode of Season 23. Listen to the end for an announcement about changes to the ...

>

Three Percent #191: Raymond Queneau

To celebrate the first-ever English-language publication of Raymond Queneau's Sally Mara's Intimate Journal, and the reissue of Pierrot Mon Ami as a Dalkey Essential, Chris Clarke (whose retranslation of Queneau's The Skin of Dreams is forthcoming from NYRB) and Daniel Levin Becker (infamous member ...

>

Edith Bruck: Recounting the Holocaust Until She Can’t

Il Pane Perduto by Edith Bruck (La Nave di Teseo, 2021) Review by Jeanne Bonner When Edith Bruck was 12 years old, she was deported to Auschwitz, and was immediately separated from her mother in a brutal scene. In her new memoir, Bruck writes that later, after being yanked away, another prisoner ...

>

The Visual Success of Women in Translation Month [Translation Database]

Women in Translation Month is EVERYWHERE. Whenever I open Twitter (or X?), my feed is wall-to-wall WIT Month. Tweets with pictures of books to read for WIT Month, links to articles about WIT Month and various sub-genre lists of books to read during WIT Month, general celebratory tweets in praise of ...

>

Best Translated Book Award 2021

Over the past year, we (mostly me and Patrick Smith) have been discussing ways to tweak the Best Translated Book Awards to continue to serve the international literature community in a way that can supplement the other major translation awards out there. When the pandemic hit and the world went on ...

>