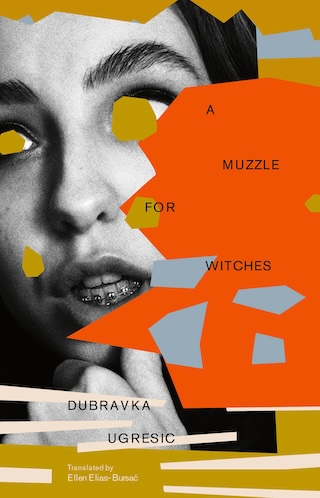

Dubravka Ugresic’s “A Muzzle for Witches”

To mark the release of Dubravka Ugresic’s final book, A Muzzle for Witches (translated from the Croatian by Ellen Elias-Bursać)—order it now from our website, or your local indie bookstore!—we thought we’d share an excerpt, which you’ll find below.

As a bit of context, this book is a conversation between Dubravka and Mermima Omeragić, although to be honest, it reads a bit more like a guided monologue. A lot of Dubravka’s typical themes are presented here—exile, writing in a “small language,” the evils of nationalism, the workings of the literary world—but this isn’t some sort of rehash or greatest hits. Knowing that this was likely going to be her final work, there’s a sense of Dubravka looking toward the future, which makes this book all the more compelling.

The bit below is from a section entitled, “The Melancholy of Vanishing,” and before we get to it, grant me one selfish aside. As you’ll see below, Dubravka alludes to an event at Powells bookstore (arranged by the amazing Jeremy Garber), and where Pilar Adón gave a reading last week. I mention that, because on several occasions, Dubravka told me she wanted me to meet her “Spanish publishers.” She never named them, and it took me far too long to realize that her Spanish publishers are Pilar and her husband Enrique! Literature is a small world.

Well, let’s get on with it:

Through many of your books runs the melancholy of vanishing. Is a happy literary outcome even possible?

I just read a report in the news about online auctions of the late Sylvia Plath’s belongings. At one auction (Your Own Sylvia) a deck of tarot cards that Ted Hughes had given to Plath was sold for $200,000. The fifty-odd items sold at auction broughtPlath’s heir, Frieda Hughes, over $1,000,000. Among them was a particularly impressive rolling pin. Quite recently a Scottish miniskirt of Sylvia Plath’s was sold at auction. The description of the skirt was much semantically richer than the reviews of the poet’s poems had ever been: “The skirt represents Plath and her personality in every way—the conflict inside, her inner art monster, cloaked by the most precise, nearly persnickety, clothes. (. . .) Plath was miserable, but she created art, and the skirt is a representation of that struggle.” I read these and other news items as if they are symbolic eulogies. Who actually died here? Literature died. At a moment when those who are nameless, the amateurs, the influencers, male and female, the politicians and porn stars, the writers and artists, the media gurus all become stars, when the genres of tell-all books, autobiography, and media-profiling have overshadowed the literary work, when The Life and Work of X is reduced to The Life of X, when what the author, male or female, wrote becomes irrelevant as long as their “product,” their “work,” refreshes the world and makes a difference, this is the moment when the death throes begin for the traditional concept of literature. If literature is to survive it must move into a zone of invisibility and go underground.

This moment seems the most narcissistic in the history of civilization. Today writers are writing their own hagiographies, or kickstarting their career by writing their own hagiography. In so doing they radically change the very essence of literature, even while being unaware of this, and mostly they are unaware. Consequently, they spur readers to write their own. And their readers have no need to tear their hair out over this—there are professional companies where nameless professionals are ready to tackle the job for them. Therefore, things are far deeper and more complex than they might seem at first glance. I won’t be far off the mark, or so I hope, if I say that the key word in our contemporary vocabulary is—archive. More than a mere word, archive is diagnosis. Diagnosis is—to use an old term expunged from our current usage—weltschmertz, world pain, with unusual symptoms. We are all of us affected by a hysterical drive to leave traces of our personal existence on the planet Earth. This narcissistic hysteria is evaluated as a positive, as success, and, in the realm of literature, as artistic success. However, the Booker Prize has not appeased the anxiety of the successee, because in success the Booker has been far outstripped by the producer of little bottles filled with one’s individual farts. Everyone has the right to leave their trace. Everyone is able to leave their trace. Traces draw attention to the fact that we exist, that we will not be erased. Therefore all evaluation is pointless, because the producer of fart jars and the author of a novel that has been awarded the Booker Prize end up equally forgotten. They will be pushed aside by a flood of new creative people, influencers, visual artists, writers, actresses selling candles perfumed with the scent of their own vaginas. They are all seeking, in a frenzy, the best possible way to leave a trace of their existence. Whence this fear of erasure, the possible disappearance of civilization? As far as literature is concerned, this fear has found its home in the genre that will be their salvation. Hagiography. Thanks to the indestructible wedding of democracy and digitalization, people can depart this world as saints. So it is that literature itself, in its mainstream, is being whittled down to a single genre, the hagiography (autobiography, autofiction), and so it is that the author, fraught by fear of disappearance, nullity, the loss of the importance of their work, the reduction of their efforts to laboring on an assembly line, step back from their text and become their own text. Their name matters more than the title of their work. Here I recall the statement of a serial killer who snorted in frustration: “Hey, how many times do I have to kill before I make it to the front page?!” Yet, who can guarantee that our lives are authentic? Who can guarantee that the saints really were saints? There is a weird company in Japan. Ingenious documentary-filmmaker Werner Herzog made the film Family Romance about it in 2019. The company provides an array of services. The client can hire people who will attend the funeral of a deceased who had no family. People can be hired to act as marital partners for those who need this kind of support (pornography, prostitution, sex are strictly prohibited). Werner Herzog zeroes in on the case of a little girl who has no father. Her mother contacts the Family Romance company. The owner spends time with the little girl, ultimately the girl opens up to him, begins to think of him as her real father. Her mother asks their rental dad to move in with them. The business owner refuses because this is not part of the deal. The end of the movie discloses a sad truth, the business owner is not part of the life of his own family. If his own family needs a father, they can only hire one.

Literature is not a toy in the hands of male or female writing egos. Literature must not (nor can it!) be placed under the control of national literatures, various ministries of culture, academies, publishers and all those bureaucratic institutions that have latched onto literature with the excuse of giving it room to breathe, yet in fact seeing to its “esteemed” demise. Literature is communication between me and those of my readers who cannot be bought, no matter who and where they are. Recently a reader from somewhere in Chile messaged me to say he had COVID and was reading my novel, Fox. He is my authentic reader. How do I know? I simply do.

Literature is what happens between me and a reader I have never met somewhere in India who discovered something in my text that I wasn’t myself aware of. Literature is what happens between me and a reader who showed up at a sparsely attended reading in Portland, bringing copies of all of my books that have

appeared in English translations, and showed that he knew by heart the most minute details which I, myself, no longer remembered. We all of us depend on the “kindness of strangers” (Whoever you are—I have always depended on the kindness of strangers) like tragic Blanche from A Streetcar Named Desire. Literature is a non-utilitarian activity. But one real reader is enough to persuade me of the meaningfulness of my work. Mystical are the paths of literature.

And while we’re on the subject of literary anticipation, Ray Bradbury’s novel Fahrenheit 451 and the unforgettable movie version, directed by François Truffaut, have been permanently etched in my memory. In the final scenes we discover the existence of a literary underground, hiding in a forest. Since possession of books is strictly banned in Bradbury’s dystopian world, the book-people have chosen to live in a parallel world. This sort of scenography does not invoke vanishing but the inkling of a new life, of revolution. The book-people are members of an underground intellectual resistance movement, where each of them commits an entire book to memory. The book-people are living libraries. The only library that exists. Who knows, perhaps a reader will appear who will choose one of my books, thereby postponing my inevitable demise. Perhaps near the end of their life, this imagined woman-book or man-book will exhale my book into the mouth of someone else, and this person will, having lived their life, pass it on to yet another. Do I believe that in the very rhythm of inhaling and exhaling lies the meaning of literature? Is any other meaning necessary? Inhalation and exhalation—life itself. With the first breath it begins, with the last it ends.

A Muzzle for Witches is available from Open Letter, Bookshop.org, and better bookstores everywhere!

Leave a Reply