The Icelandic Connection

If you’re a long time reader of Three Percent and/or literature in translation, I’m sure you’ve heard of Deep Vellum, and probably know most of their history. But to kick off my series of posts about their September/October books—and to put the numbers below in context—it’s probably worth a quick recap.

Back in the spring of 2012, Will Evans called me to see if he could spend a summer in Rochester learning about Open Letter, all with a goal to starting his own press. He had recently read The Three Percent Problem: Rants and Responses on Publishing, Translations, and the Future of Reading and was inspired by the bit in there about how instead of whining about how there aren’t enough translations, people should go out and start their own presses.

That might probably be terrible advice, but whatever! We need more people in the world with quixotic ideas that they will into existence!

The summer of 2012 was absolutely magical for me. We spent so much time watching Euro Cup games and breaking down every aspect of the publishing industry. We were basically inseparable the whole time—which is why Will Evans was “Bromance Will” after Will Vanderhyden, aka, “Willscosin”—and within no time, Will was charming everyone at the Frankfurt Book Fair and talking to Consortium about distributing Future Tense Deep Vellum.

I’m on Deep Vellum’s board, so I’ve seen some of Will’s growing pains first hand. But after a bit of a rough patch, everything seems to be getting back on track, both with the books (five! are coming out this fall) and with the Deep Vellum bookstore.

Now that there are forty Deep Vellum titles in the Translation Database, it seems like a good time to look at where Deep Vellum has been, what their publishing profile is, how they fit into the overall publishing and nonprofit landscape, their editorial leanings, and whatever else comes out of reading a bunch of books from a single press all in a row.

Öræfi—The Wasteland by Ófeigur Sigurdsson, translated from the Icelandic by Lytton Smith (Deep Vellum)

Yes, Iceland again!

There are a number of interesting things about this book: where it’s set (in the southeast of Iceland, not Reykjavik), the nested narrative (it’s a letter that the author received from Bernhardur Fingurbjörd recounting a letter that Dr. Lassi wrote about her treatment of him), the fact that it’s as funny as it is serious (long-standing complaint of mine about how most literary translations are void of humor), and it’s ecological concerns (becoming more and more of a trend, especially now that we have, gulp, like 12 years left before everything falls apart).

Here’s a quick summary of what the book is about: Bernhardur grows up in Austria, but becomes obsessed with Iceland thanks to National Geographic and the fact that, while traveling through Iceland, his mom was assaulted and his aunt murdered.

As a toponymist, he’s particularly interested in the Öræfi area, which used to be called Herad (meaning “The Province”) until the volcano erupted in the 1300s and destroyed everything. That’s why it was renamed Öræfi, or, “The Wasteland.” Bernhardur is interested in all the placenames and the stories they tell about the Icelanders.

The novel opens with him crawling out of the mountain, frostbitten and with a serious bite from some sort of renegade sheep. Dr. Lassi, a local vet, ends up saving his life by amputating his leg, buttocks, and cock and balls. (His “pecker” ends up in Iceland’s Phallological Museum.) She then gets his story and relates it all in a manic, all-over-the-place fashion:

What the hell is a gusthlaup? Dr. Lassi asked the interpreter, I keep writing this damn word in the report, taking it from the accounts that stream in here, but I have no idea what a gusthlaup is! The interpreter replied that she didn’t know what gusthlaup meant. Get Hálfdán from Tvíker! Dr. Lassi ordered the interpreter, he’s down at the meeting, no, Hálfdán is the ornithologist . . . Sigurdur! Fetch me Sigurdur, or whichever of the brothers is the geologist? Just get any of them, they must all know the word, they’re so learned, these people, and it has to be clear in the narrative.

There’s a lot more to this book, including a surprise ending and the true story of the only murder ever to take place in that part of Iceland. But the unrelenting lightning quick pace of the voices is what really makes this book work. It’s a bit like a Bernhard novel (the protagonist is a direct reference to everyone’s favorite bitter Austrian), but not quite so dark or claustrophobic. (Which is an ironic thing to write given the ending.) In a way, it reminds me of Tram 83 in its attention to voice and cadence.

Which brings me back out of talking about the book—go buy it! it’s worth reading—and into talking more about Deep Vellum’s history and what it is they’ve published.

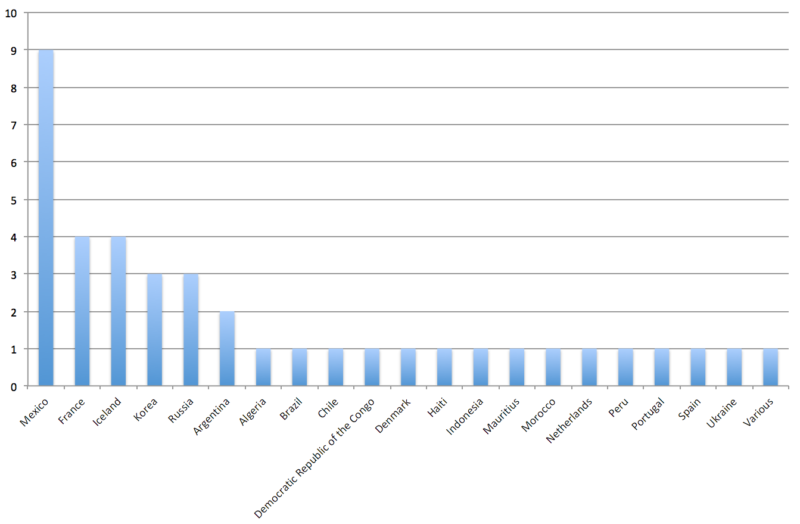

One of the most noteworthy things about Deep Vellum is how many different countries they’ve published books from. The first forty titles are from twenty-one different countries. (Actually more than that if you count all the countries represented in Banthology separately.) That a really solid commitment to find books from around the world.

I don’t know the stories behind all of Will’s books, but I know that Mexico was a priority for him given the press’s physical location and current politics. And I know that most of the Korean books came out of a trip to Seoul that Will, Ross from New Vessel, and I went on a few winters ago.

And I believe that Öræfi came about when Will met Ófeigur in a hot pot while attending the Reykjavik Literary Festival, which Will was attending because he was publish Jón Gnarr’s trilogy. Soaking in a hot pot is how all publishing decisions should be made.

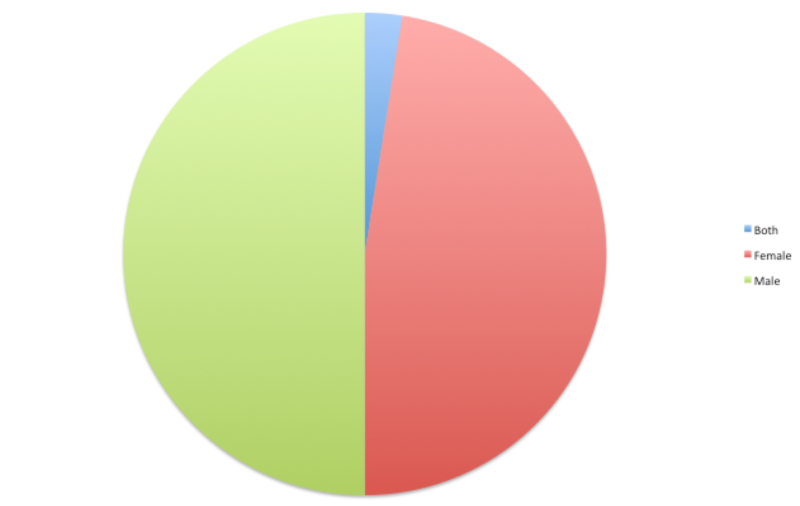

This balance is also worth noting. There’s been more and more attention paid to publishing women writers in translation, but it’s still pretty disproportionate. In the case of Deep Vellum though, they’ve published 20 books written by men, and 19 by women. (And one anthology.) That’s amazing! I know that this was always Will’s intent, and it’s admirable to see how well he’s stuck to this part of his mission.

More coming soon—including a super long post on Thursday . . .

*

The Taiga Syndrome by Cristina Rivera Garza, translated from the Spanish by Suzanne Jill Levine and Aviva Kana (Dorothy)

Dorothy would be another great press to read a bunch of their books in a row to learn about their editorial vision and whatnot.

But for now, I just want to say that this book really lives up to the hype. A lot of booksellers were all over this during the summer when they received the galley, and it’s one of the fall titles I’ve been most looking forward to.

A highly stylized mystery, it’s about a detective’s attempt to find a woman who fled from her husband with another man, yet sends her husband a number of cryptic notes, raising the possibility that she wants to be found. The “mystery” takes a backseat both to the detective’s musings on love and how it can leave, her relationship with the translator she hires to help her, the strange occurrences in the snowy taiga, and the evocative, crystallized prose.

No one can really know why someone leaves their home, not even, or above all, the one that leaves. But why would anyone pursue someone who flees to the Taiga? The answers, in my case, were numerous: for money, of course. For an Adam’s apple that threatened to break the leathery skin of a man’s neck? For that as well. In order to have the opportunity to ask a woman, directly, while grabbing her by the right arm in a struggle that was nearly pointless and even less decent, why, what for? For that, that’s why. Also. In order to see her eyes, terrified. In order to sink into those eyes, an insect of the boreal forest. Something that stings or bites. A tiny warrior. When inside, to buzz. The question or complaint, to pierce: tell me why. Tell me where this passion comes from. What’s it made of. How or what.

You can read a longer excerpt here. And equally interesting is this essay by Christina Rivera Garza on “The Unusual: A Manifesto,” which was written to mark Stefan and Tara Tobler’s decision to publish only women writers for a complete year:

In the wake of the #MeToo movement, as new generations of women worldwide forcibly expose the cruel nature of the gender hierarchies (and binaries) that structure our daily lives, while many reject the possibility of being either physically disappeared or culturally erased, the decision to only publish women authors may appear unusual, but it is urgent. I am convinced that writing is a critical practice: true, bold, brave, formally adventurous writing should have the ability to change perceptions and experience; the disordering of the senses talked about by Rimbaud, inextricably linked with the disordering of everyday life as we know it. Producing unusualness, writing expands our sense of what is possible. Imaginable. Livable. Publishing women authors is not a minor component in this process. [. . .]

I agree with the Argentinian writer Josefina Ludmer in that I believe literature now exists in a cultural phase we can describe as post-autonomous. Literature’s cultural capital guaranteed its status as an autonomous field of inquiry and practice throughout the twentieth century. However, it had declined precipitously by the end of the millennium, changing too its sphere of influence and the accessibility of its resources. As Josefina Ludmer says, instead of discreet units wrapped in clearly delineated genres that presented themselves as imaginary worlds with a fragile connection to community, today’s writings “do not admit literary readings. That is to say, it does not matter whether they are literature or not. We don’t know either whether they are reality or fiction. They inscribe themselves locally and in everyday reality in order to ‘produce the present,’ and this is precisely their relevance.”

Leave a Reply