The Hospital [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards.

Justin Walls is a bookseller with Powell’s Books in Portland, Oregon and can be found on Twitter @jaawlfins.

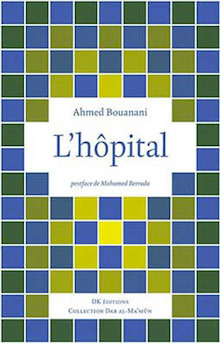

The Hospital by Ahmed Bouanani, translated from the French by Lara Vergnaud (Morocco, New Directions)

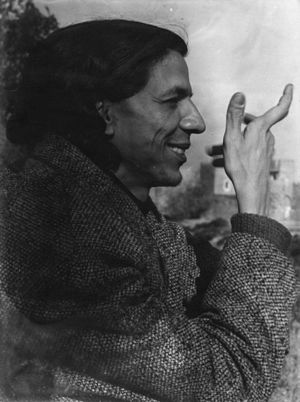

In a 2002 episode of the seminal “squigglevision” successor Home Movies, budding Foucault-ian and irascible boob Coach McGuirk stumbles backwards into a series of quarter-baked revelations regarding the prison-industrial complex. Initially alighting on the self-pitying canard that pampered prisoners—when you think about it—enjoy a higher quality of life than that of your average youth league soccer instructor, the H. Jon Benjamin-voiced everyman then advances his threadbare theorizing to its only logical conclusion: “We all live in our own prisons, Brendon. We’re all trapped in these bodies.” After spiraling into an overlapping bit of fatalistic call-and-response with his eight-year-old interlocutor, even the conversation itself is revealed as a form of incarceration. No book in recent memory (or any book appearing in English in 2018, let’s say) better exemplifies the outer-limits elasticity of this metaphor than Moroccan multi-discipline artist Ahmed Bouanani’s The Hospital, replete with its own cartoonish cast of miscreants condemned to an eternity of interlocking bureaucracies, shunted away “beneath tons of indifference and oblivion.” A bawdy, oneiric, brilliant novel, translated by Lara Vergnaurd, The Hospital depicts no less than the grand illusion of autonomy as experienced by a patient manifest that includes names like Rover, Guzzler, and Fartface.

It’s fitting that much of the past year’s finest fiction was preoccupied with the notion of being confined in one way or another. Denis Johnson’s “The Starlight on Idaho” and “Strangler Bob” (rehabilitation-as-prison and prison-as-prison, respectively) from his towering swan song The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, Willem Frederik Hermans’ corkscrewing An Untouched House (war-as-prison, oasis-as-paradise, paradise-as-prison), and the face-melting speedfreak-ery of Jose Revueltas’ The Hole (prison-as-prison again) each qualify as exemplary entrants into the literature of detainment. These works collectively trend toward the brief and ghastly end of the spectrum, spewing invective or violence with appropriately cauterizing results, and doing so from a staunchly paleolithic (read: male) viewpoint.

It’s fitting that much of the past year’s finest fiction was preoccupied with the notion of being confined in one way or another. Denis Johnson’s “The Starlight on Idaho” and “Strangler Bob” (rehabilitation-as-prison and prison-as-prison, respectively) from his towering swan song The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, Willem Frederik Hermans’ corkscrewing An Untouched House (war-as-prison, oasis-as-paradise, paradise-as-prison), and the face-melting speedfreak-ery of Jose Revueltas’ The Hole (prison-as-prison again) each qualify as exemplary entrants into the literature of detainment. These works collectively trend toward the brief and ghastly end of the spectrum, spewing invective or violence with appropriately cauterizing results, and doing so from a staunchly paleolithic (read: male) viewpoint.

However, there’s a gee-golly brand of braggadocio that permeates The Hospital‘s ersatz penitentiary, baldly farcical boasts deployed as incantations against the monotony of the grind. (One could easily conflate this internment with modern-day office culture, but I’ll avoid that.) In short: defense mechanisms masquerading as macho chest-thumping. Such ever-evolving bull sessions, true to form, favor the grisly (axe murder) or the scatological (ill-timed diarrhea), each fabricator-in-question hastily appending a buttress or turret to their invisible architectures mid-telling. The cumulative effect becomes akin to gazing at Bruegel the Elder’s The Triumph of Death as re-imagined by Carl Barks—a madhouse rendered in terms both blood-curdling and comedic. It’s a woefully unfair fight between sprawling atrocity and the minuscule objections of ineffectual outcasts who, defying all reason, continue to puff themselves up in opposition of the inevitable onslaught of decay. As the adage goes, you have to laugh to keep from crying.

Where Bouanani’s flickering labyrinth truly excels is in its utter obliteration of temporal cognizance, a non-linear un-being born of isolation. Few meaningful markers from the outside breach the titular institution, “a frozen body, walled in from every angle.” The occasional visitor soon forgotten, the smell of the ocean on the night breeze, and little else. Even more scant are the instances of inmates slipping through the gates on the rare day-pass, returning to former haunts only to find themselves becoming wraiths in the light of a world that has banished them from its embrace. Instead, The Hospital is equal parts foxhole and group chat, awhirl with the sort of anecdote and bluster and meandering introspection endemic to a shared sentence that rapidly diminishes in terms of beginning or end, morphing into a Möbius expanse of middle. It would be impossible to miss the purgatorial implications at hand, but what squeezes through the cracks amidst the gloom is an inherent sense of camaraderie, of a common plight between disparate fools fated to wile away the hours roaming the halls of one another’s mind palaces. When, in one exchange, a lush botanical array is conjured on the spot (“A caprice of a mad gardener, untroubled by aesthetics or harmony, who, on a whim of his imagination assembled a collection of plants that have absolutely nothing in common!”) it feels like a merciful palliative administered to a fellow sufferer, another in a line of lost boys left to their own devices, as well as an apt description for the mutable structure itself.

Where Bouanani’s flickering labyrinth truly excels is in its utter obliteration of temporal cognizance, a non-linear un-being born of isolation. Few meaningful markers from the outside breach the titular institution, “a frozen body, walled in from every angle.” The occasional visitor soon forgotten, the smell of the ocean on the night breeze, and little else. Even more scant are the instances of inmates slipping through the gates on the rare day-pass, returning to former haunts only to find themselves becoming wraiths in the light of a world that has banished them from its embrace. Instead, The Hospital is equal parts foxhole and group chat, awhirl with the sort of anecdote and bluster and meandering introspection endemic to a shared sentence that rapidly diminishes in terms of beginning or end, morphing into a Möbius expanse of middle. It would be impossible to miss the purgatorial implications at hand, but what squeezes through the cracks amidst the gloom is an inherent sense of camaraderie, of a common plight between disparate fools fated to wile away the hours roaming the halls of one another’s mind palaces. When, in one exchange, a lush botanical array is conjured on the spot (“A caprice of a mad gardener, untroubled by aesthetics or harmony, who, on a whim of his imagination assembled a collection of plants that have absolutely nothing in common!”) it feels like a merciful palliative administered to a fellow sufferer, another in a line of lost boys left to their own devices, as well as an apt description for the mutable structure itself.

The Hospital (as well as the hospital) operates on a borrowed-time concept that situates all things in the liminal realm of contradiction. Alive or dead, healthy or infirm, inside or out—these distinctions blur beyond recognition within Bouanani’s mirage-like convalescent bunker, giving way to a rhetorical mode familiar to anyone presently feeling likewise immured by the specters of income inequality, rapacious insurers, political corruption, impending ecological collapse, and so on. Damned if you do or don’t; it hardly matters. Perhaps only Wolfgang Hilbig’s recently translated The Females performs a commensurate speaking-across-eras trick, it being a seemingly beamed-in manifesto for a terminally horny and reflexively aggrieved strain of leering masculinity rampant among the current discourse. Though, while Hilbig’s decomposing narrator is something like an irradiated Ignatius J. Reilly, Bouanani’s—assigned the nom de plume Smart Ass—never exhibits less than utmost humanity, regardless of how bleak his reality has become. That balancing act alone makes this book worthy of the prize.

Beyond anything else, it’s the unsentimental adherence to hope that confirms The Hospital as an essential work of precariousness, deprivation, and resilience. During an uncommon bout of revelry to celebrate a momentary respite from persistent rainfall, the detainees of the hospital erupt in a chant of “May God bless the hell where we spend all our day—here!” Without fail, thunderclouds rear their heads and resume the deluge. Just like that, the party’s over. The storm gathers over us all, but for now we remain blissfully trapped in these treacherous, fallible, hell-bent bodies.

Leave a Reply