Love in the New Millennium [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards.

Rachel Cordasco has a PhD in literary studies and currently works as a developmental editor. She also writes reviews for publications like World Literature Today and Strange Horizons and translates Italian speculative fiction. For all things related to speculative fiction in translation, check out her website: Speculative Fiction in Translation.

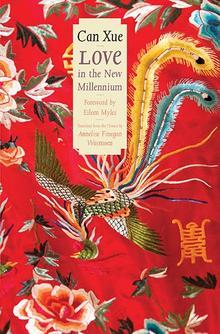

Love in the New Millennium by Can Xue, translated from the Chinese by Annelise Finegan Wasmoen (Yale University Press)

Love in the New Millennium is a work of operatic magical realism; a book with many layers, many shifting romantic relationships, and no clear plot. Like Frontier, one of Can Xue’s previous novels, Love invites us into the hazy, sometimes frustratingly-elusive worlds of a handful of characters, many of whom are desperately trying to find a “home.”

This search for one’s ancestral homeland or childhood home runs throughout the book, even though each chapter focuses on a different person or pair of lovers/friends/acquaintances. Indeed, Can’s novel is like a dreamy, hyperbolic response to the saying “You can’t go home again.” Each time a character tries to find relatives or a childhood home, they’re either met with otherworldly people who may or may not be ghosts, or they simply can’t find the place at all. When Niu Cuilan decides to visit her homeland, she finds her aunt and uncle living in the old house but looking mysteriously wizened and ancient. The aunt doesn’t even speak—she chirps like a cicada. And if that seems . . . strange, you just have to keep reading. At one point, Cuilan can’t sleep and casually decides to go stand inside the wall and sleep that way for the rest of the night. As one does. Oh, and her aunt and uncle can also fly.

This search for one’s ancestral homeland or childhood home runs throughout the book, even though each chapter focuses on a different person or pair of lovers/friends/acquaintances. Indeed, Can’s novel is like a dreamy, hyperbolic response to the saying “You can’t go home again.” Each time a character tries to find relatives or a childhood home, they’re either met with otherworldly people who may or may not be ghosts, or they simply can’t find the place at all. When Niu Cuilan decides to visit her homeland, she finds her aunt and uncle living in the old house but looking mysteriously wizened and ancient. The aunt doesn’t even speak—she chirps like a cicada. And if that seems . . . strange, you just have to keep reading. At one point, Cuilan can’t sleep and casually decides to go stand inside the wall and sleep that way for the rest of the night. As one does. Oh, and her aunt and uncle can also fly.

Cuilan’s sometime-lover, Wei Bo, seems to have the opposite problem when it comes to “going home again,” since he simply doesn’t know where to look. This might just be because, whenever his father took Wei Bo there by train, the father made him wear a blindfold for the entire ride, telling Wei Bo that if he took the blindfold off, they’d never reach their destination. And though Wei Bo tries to piece together scraps of memory about the sights and sounds he remembers from that old house, he can’t even tell if it was in the country or the city. When Wei Bo later voluntarily becomes an inmate in the local prison, we’re told that most of the inmates actually want to be there, to find a kind of community and home that is concrete and uncomplicated.

Sight and blindness are key to Wei Bo’s character, especially when we learn that one of his uncles once gave him a magnifying glass that magnified for the eye and magnified eyes. That is, when Wei Bo looked through it to see the pages of an ancient book, he was confronted by a three-dimensional eye, and when he expressed amazement, his uncle seemed surprised at Wei Bo’s surprise. Thus, vision is untrustworthy and multidimensional, offering information that seems irrelevant or deceptive—perhaps this was why Wei Bo’s father refused to let him see the journey to their ancestral home?

And then there’s the opera singer. A woman who has sung La traviata for forty years is only referred to as “the Lady of the Camellias” for the rest of the story—that is, her identity is synonymous with the character she plays in the opera. Can Xue’s use of La traviata is itself interesting because the opera has already gone through many iterations before becoming a part of Love: first it existed as the romantic, semi-autobiographical novel La Dame aux Camélias (1848) by the French author Alexandre Dumas fils; then Dumas adapted it for the theater (1852); after which Giuseppe Verdi used it as the basis for his opera La traviata (“The Fallen Woman”), which was itself set to an Italian libretto and first performed in 1853. If this sounds like a game of “telephone,” you’re not wrong.

Why, then, does Can Xue weave La traviata throughout this book, and then title one of her chapters “Sentimental Education,” in an obvious nod to Gustave Flaubert’s L’Éducation sentimentale (1869)? La Dame aux Camélias and L’Éducation sentimentale, and Love as well, are concerned with complicated, uncertain romantic relationships. Men and women have affairs, women turn to prostitution to escape a gray world, people switch partners depending on shifting desires. This constant running around in search of a past home and present relationship reveals the rootlessness and dislocation that Can’s characters all feel in varying degrees. Their pain and desires are best expressed, then, by way of opera—hyperbolic and stylized, with plots that are often centered on love and passion. It’s no surprise then that, as Eileen Myles writes in her Introduction, “[t]here is no small talk, no phatic. It’s emphatic all the time.”

Why, then, does Can Xue weave La traviata throughout this book, and then title one of her chapters “Sentimental Education,” in an obvious nod to Gustave Flaubert’s L’Éducation sentimentale (1869)? La Dame aux Camélias and L’Éducation sentimentale, and Love as well, are concerned with complicated, uncertain romantic relationships. Men and women have affairs, women turn to prostitution to escape a gray world, people switch partners depending on shifting desires. This constant running around in search of a past home and present relationship reveals the rootlessness and dislocation that Can’s characters all feel in varying degrees. Their pain and desires are best expressed, then, by way of opera—hyperbolic and stylized, with plots that are often centered on love and passion. It’s no surprise then that, as Eileen Myles writes in her Introduction, “[t]here is no small talk, no phatic. It’s emphatic all the time.”

The tightly controlled, stylized, dream-like non-plot, with its carefully crafted characters all looking for the same thing in different places and with different people—this is why Love in the New Millennium should win.

[…] SFF IN TRANSLATION. Rachel Cordasco’s “Love in the New Millennium [Why This Book Should Win]” is one in a series of thirty-five posts about every title longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated […]