Architecture of Dispersed Life: Selected Poetry [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards.

Aditi Machado is the author of Some Beheadings and the translator of Farid Tali’s Prosopopoeia. She is the former poetry editor at Asymptote and the visiting poet-in-residence at Washington University in St. Louis.

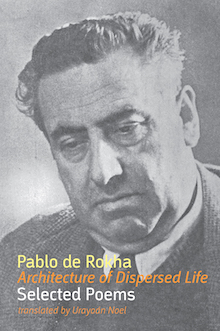

Architecture of Dispersed Life: Selected Poetry by Pablo de Rokha, translated from the Spanish by Urayoán Noel (Chile, Shearsman Books)

Wouldn’t it be perfectly delicious, I think, wouldn’t it just, if all I did here was quote from—

Adding up the world, the whole world, Yankeeland, Yankeeland opens its IMMENSE mouth, immensely full of dead birds! . . .

—this vicious little (big) book? Maybe that’s all I need to do, but then, I think, what if—what if, not? What if they just don’t—

Like an ample blonde cow, like an ample blonde cow, Yankeeland ambles arounds chewing over, chewing over, chewing over the future of beasts and defecating paradoxes; the cowboys bellow their green sonnets kicking and screaming, cornered, like buffaloes, like buffaloes bellowing prehistorically, bellowing, like rhinoceros chariots, the poems of the freest man, the freest, the freest …

—see what I see? Because do we (and by “we” I mean those of us, in our various shapes and colors, trained to understand “the” avant-garde as a set of Anglo experimenters who “did” “things” with syntax and perspective and I still love you Woolf and Stein) know anything about “the” avant-garde that’s—

Yankeeland flicks the ash, the ash, the honorable ash of its capitalist cigar on LIFE’s wrinkled face and smiling, smiling, it says to the sun: Sir,

—not European and not United St-

yield the sidewalk to me! … yield the sidewalk to me! … ! … , and the SUN, the SUN, the SUN complies . . .

—atesian? Ay, there’s the rub! And wouldn’t it be so very perfect if “we” living in (if not belonging to) the United States were to reward a book so very, very and viciously critical of this—

Yankeeland the COSMIC, the COSMIC Yankeeland plays golf, plays golf, plays golf with the great ball of THE EARTH…

—very land.

*

The quotations above are all from a single long poem, “Yankeeland,” by Pablo de Rokha—described in a blurb by Daniel Borzutzky as “a major Chilean poet of the early 20th century, who ought to sit front and center alongside Neruda, Mistral, Huidobro, Vallejo and Girondo”—translated by the stateless poet-performer-thinker Urayoán Noel. The substantial paratext in this 300-page selected volume positions de Rokha (1894-1968) at the forefront (indeed, often, before Neruda) of Chilean avant-garde poetics, but also as an outsider: an indigenous poet, a polemicist, an artist of great fury, talent, and lust for life. All this is evident in simply the one poem, “Yankeeland” (from an early book published in 1922), but Noel offers us selections from almost all of de Rokha’s work, ranging from his early anarchism and formal daring to a middle period of explicit political activism as well as the elegiac turn of his final years.

The quotations above are all from a single long poem, “Yankeeland,” by Pablo de Rokha—described in a blurb by Daniel Borzutzky as “a major Chilean poet of the early 20th century, who ought to sit front and center alongside Neruda, Mistral, Huidobro, Vallejo and Girondo”—translated by the stateless poet-performer-thinker Urayoán Noel. The substantial paratext in this 300-page selected volume positions de Rokha (1894-1968) at the forefront (indeed, often, before Neruda) of Chilean avant-garde poetics, but also as an outsider: an indigenous poet, a polemicist, an artist of great fury, talent, and lust for life. All this is evident in simply the one poem, “Yankeeland” (from an early book published in 1922), but Noel offers us selections from almost all of de Rokha’s work, ranging from his early anarchism and formal daring to a middle period of explicit political activism as well as the elegiac turn of his final years.

This is almost too much, Urayoán Noel, and I can never say no to “too much.” There is indeed “too much” to quote from and “too much” praises to sing of this translator, so I’ll only say that I watched some YouTube videos of Noel performing his work and believe that it is the fullness of this performative artistry, its critically somatic intelligence, that emerges also in his translations—in having to recreate de Rokha’s syntactical and sonic excesses, his idiosyncratic spelling, his outrageous and botanically precise diction, as well as his refusal to restrain language by means of what I’ll call semantic “border control.” An example of this latter is taken, here, from the book-length Southamerica (1927):

. . . the sun in the breakdown of autumn shines like ripe fruit the white guardians carry the dawn in their belt and the zeal of uselessly greek bastards puffs the chests of the honest pines each one has a water jug yes a water jug and smiles like a smartly dressed planet similar to a skyscraper to a prisoner to a sardine myself walking singing resinging countersinging with my subterranean papers my red pants my yellow hat my green sandals and my transparent jacket the color of god and my voice as black and thick as corpse moonshine …

This massive block of a prose poem is the embodiment of a landscape: “The punctuation-less blocks of text allow for endless and vertiginous chains of metaphors and modifiers, and for radical synaesthetic slippages, as the sights of rural Chile are also its sounds, smells, tastes, and bodies,” writes Noel, who also points out that while South America is obviously located in opposition to the Global North in the early poem “Yankeeland,” de Rokha’s Southamerica of 1927 is its own space, not reliant on anything but itself to be (un)intelligible, to simply be.

I am grateful to Noel not only for his translations but for his selection and arrangement of these texts, as well as his scholarship. Architecture of Dispersed Life is an extraordinarily generous English-language introduction to Pablo de Rokha and indeed the very first one in book form.

I am grateful to Noel not only for his translations but for his selection and arrangement of these texts, as well as his scholarship. Architecture of Dispersed Life is an extraordinarily generous English-language introduction to Pablo de Rokha and indeed the very first one in book form.

Much of de Rokha’s poetry feels terrifying relevant in our current, unhappy times (see the excerpts from “Yankeeland” above). It is also evident that de Rokha is, as they say, “a man of his time,” and even, a man of our time, given his depictions of women’s bodies, frequently naked and mindless, to convey his sense of a world “riven” by violence, and given his obvious homophobia and perhaps less obvious racism. I am grateful to the translator for acknowledging de Rokha’s “vitalistic hetero-masculinism and … the unchecked privilege that comes with it, even as his work consistently questions privilege in other ways (for instance, by affirming the working-class, the rural, the subaltern, and the indigenous).” In championing this book, I am also championing the sort of reading that is willing to contend with and reject aspects of our literary ancestors (many of my Anglo literary heroes are under-criticized for their bigotry, if criticized at all) that we wish not to condone or allow to continue.

I’ll end with where I began, with some quotations, which I hope will circulate, and excessively, from this big (little) book:

That’s why one understands more by living than my thinking, because living is thinking, with each and every muscle.

—“Architecture of Dispersed Life,” 1934

let the poem become being, action, will, organism, virtues and vices, let it constitute, let it determine, let it establish its atmosphere, its atmosphere and the great custom of the gesture, the act’s judgment

—Equation [Song of the Aesthetic Formula], 1929

everything lurks and i contain it and i desire it all and everything defines me happy from the other shore whose law presides over my boundless system an order emanates from disorder

—Southamerica, 1927

My voice was walking down the void and my voice got tangled in my voice.

—U, 1926-27

I hate, hate the utilitarian, coarse, quotidian, prosaic work, and I love the illustrious idleness of the beautiful; to sing, sing, sing . . .—that’s all you know, Pablo de Rokha!

—The Moans, 1922

Leave a Reply