Dezafi [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards.

P.T. Smith reads, writes, and lives in Vermont.

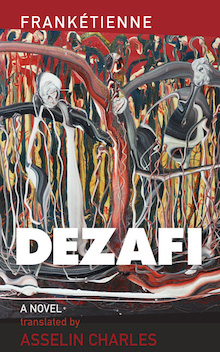

Dezafi by Frankétienne, translated from the French by Asselin Charles (Haiti, University of Virginia)

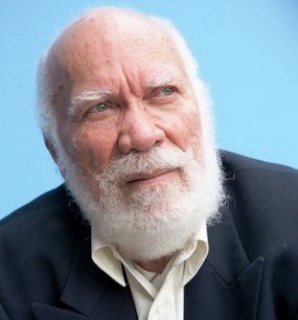

Every year, the BTBA introduces me to books I’d otherwise completely miss. Whether it’s because I read it while a judge, because it’s on the longlist, or because I had the wildly fun advantage of watching them discuss these books and some lodged in my head, like Asselin Charle’s translation of Frankétienne’s Dézafi. It was one of a few books rooting to make the longlist despite not having read it. I’ve read Frankétienne before, apparently, though I remember nearly nothing of Ready to Burst. Ultravocal has been forthcoming from Archipelago for what seems like years. He’s the master of Haitian literature. This is a “zombie” novel. How can you not root for that?

My copy arrived after the longlist was announced and I dove in. I started it at the same time I was reading another book on the list. Dézafi took over, and that’s nothing against that unnamed book, but Frankétienne just gives us that damn good of a book. And the reason it should win this year is because this is a book only the BTBA could recognize. The entire longlist is a demonstration of how special and full of variety this award is.

Let’s get the fun, and deceptive, pitch out of the way first. This novel has zombies! It’s the second book on a BTBA longlist to have zombies! But this was also written in 1975. It’s not zombies as we know them. It’s not a literary novel playing with genre tropes to make high-minded people feel comfortable reading about monsters, spaceships, of fantasy kingdoms. The zombies are mostly called zonbis, and they’re humans who have had their soul stolen by a sorcerer, a Vodou priest. These are Haitian zombies, a parable for poor, abused workers, not George Romero’s zombies, and certainly nothing like modern and increasingly desperate attempts to add some new spin to zombies. Instead Dézafi is straightforward in that Frankétienne has no interest in saying something about the idea of zombies, but instead they are just the perfect and natural fit to the story he’s telling. These zonbis were made, they exist, they suffer, and they will have their revenge. Despite this warning about Dézafi, something remains true: the BTBA has no hesitation paying attention to genre. Last year’s winner is packed full of sci-fi elements. This is a literary award that embraces genre as an element of literature alongside any style, trick, tool, device, whatever.

Let’s get the fun, and deceptive, pitch out of the way first. This novel has zombies! It’s the second book on a BTBA longlist to have zombies! But this was also written in 1975. It’s not zombies as we know them. It’s not a literary novel playing with genre tropes to make high-minded people feel comfortable reading about monsters, spaceships, of fantasy kingdoms. The zombies are mostly called zonbis, and they’re humans who have had their soul stolen by a sorcerer, a Vodou priest. These are Haitian zombies, a parable for poor, abused workers, not George Romero’s zombies, and certainly nothing like modern and increasingly desperate attempts to add some new spin to zombies. Instead Dézafi is straightforward in that Frankétienne has no interest in saying something about the idea of zombies, but instead they are just the perfect and natural fit to the story he’s telling. These zonbis were made, they exist, they suffer, and they will have their revenge. Despite this warning about Dézafi, something remains true: the BTBA has no hesitation paying attention to genre. Last year’s winner is packed full of sci-fi elements. This is a literary award that embraces genre as an element of literature alongside any style, trick, tool, device, whatever.

What else is it that makes Dézafi deserve to win the title this year? How about that it’s simultaneously an immensely complex and challenging novel and an engaging read? It’s got sections in italics, the voice of the zonbis: “Sleep rise look walk eat lick finger blow fall run spend the day hungry. Talk nonsense. Tongue heavy. Tongue shredded in a thousand pieces. Full belly. Twisted guts. Thirsty for water.” The writing here can be fragmented, with partial lines, and spaced across the page, calling to mind poetry. It’s the collective voice of a people crying out. They want to be heard. They want their souls back. They are also a voice of Haitian tradition, the crossroads, dance. These sections are the most romantic sections, beautiful and fun and strange. They give the zonbis empathy: “Our skins are raw. We’re wounded to our bones.”

The most accessible, straightforward, plot-based narrative is in normal font and tells the story of humans involved with the zonbis, including the sorcerer Sintil and his, uh, daughter/servant/inappropriate relationship, Siltana, and the assistant Zofè. Siltana will fall in love with one of the zonbis, feed him salt to “poison” him by making him strong, leading to rebellion. The writing here is still beautiful and wild and unique, but it’s also where we learn how zonbis are made, the past of the hero zonbi Klodonis, and where the love story between him and Siltana comes through.

The final of the three main types of narrative is in bold text, with slashes to break up lines: “All roads cross in the woods / we rise up early / ass kissing flatterers go a long way / even with a single match you can light a fire /a dandy at the cockfight / gamecocks fight / we break our backs working” These are a bit of everything: the story; the zonbi’s lives, the cockfighting celebration. They’re a song of Haiti, the spine of this book.

There are other types of text, and there are section breaks, and a diagram. It’s complex is what I’m saying. It’s intricate in that way where as you read you feel that there are connections everywhere, that the book is overgrown with details and references and ties between sections and lines and ideas and characters and Haitian traditions and history. You feel it. You make out what you can. You don’t have to see the way the intricacies work to be rewarded with the pleasure they give off. The ride is a the point, and the whole way, you know that you could go deeper, work harder, read closer, reread.

So: genre, joyous, welcoming, yet difficult literature. What else makes for a BTBA book? I’m no Chad Post, so I haven’t looked at any numbers, I have no charts, no actual data, but I’m still going to claim that BTBA is one of the most diverse awards out there, each and every year. In terms of gender of the authors and translators, in terms of language, country of origin, time period, etc., I don’t believe any award cooks up lists like these ones.

Let’s make another claim: a fairly diverse award list isn’t that hard to make. You’re gonna want to start with the judges. Get some different tastes, different perspectives and backgrounds. Then you’re gonna want to make the longlist long. It helps. And this isn’t just throwing a bone out to some books to pad out a list and make it diverse. Naw, not only are all the books on the longlist each year books some judges are passionate about, books that start as longshots that barely made the list often go on to make the short list…and maybe win?

Let’s make another claim: a fairly diverse award list isn’t that hard to make. You’re gonna want to start with the judges. Get some different tastes, different perspectives and backgrounds. Then you’re gonna want to make the longlist long. It helps. And this isn’t just throwing a bone out to some books to pad out a list and make it diverse. Naw, not only are all the books on the longlist each year books some judges are passionate about, books that start as longshots that barely made the list often go on to make the short list…and maybe win?

Throughout the year, the judges comment on a spreadsheet where every eligible translation is listed. All books are assigned to a judge to read, workload neatly distributed. This means they are reading books they would never otherwise never come across, they’re giving it a chance it might not otherwise get. These are the books they want to find. The books that would always get their attention will still get it, but the spreadsheet helps those other books.

The judges want to find books like Dead Rose, Dézafi, Congo, Inc., and Slave Old Man. They read and they discuss with intentionality. I watched these discussions happen. There’s a desire for a diverse list. That desire is there because it’s how they read. They read with admirable openness, wanting new, wanting challenges. Diverse literature is a leap towards those things. The judges are seeking the best translated books on offer. What that means, they determine, with as many contributing factors as they want. With some judges, the intentionality towards diversity is greater than others. This is a good thing. No one is reading with an agenda, no one is forcing anything, but with honesty, passion, discussion, and varied intentions, a special award list rises.

Dézafi is representative of what the BTBA can accomplish. Of the type of book it can help readers uncover. It’s the first novel written in Kreyòl. It’s brilliant, both structurally and as a story. The translation is wonderful (there are a few occasions where Charles adds a footnote, explaining a meaning and most of the time it’s not necessary because he nailed the translation already). It’s culturally important, both to Haiti and to anyone interested in world literature. Pulling a quote the afterword from Frankétienne himself, “Dézafi was first of all for me an aesthetic literary experience at the level of the Creole language. Dézafi is first and foremost the novel of the Haitian language, but as a language is indissolubly linked to the becoming, to the destiny, the lived situation of a people.” He created a work of art in the language of the people, as an aesthetic and a political act. Charles has given that book to us in English. It deserves victory.

Dear Mr. Smith,

Thank you for this wonderful review of Dezafi. Thank you for rooting for this unusual novel and one of the few works of fiction by a Haitian author to be available in English. Allow me, though, to redresss an important error in the piece: Franketienne wrote Dezafi in Haitian Kreyol, and it is this original work I translated into English. The author did a French translation of his own work, which was published in France; this French version is different from the original in many ways. Anyway, for historical and scholarly purposes, I chose to translate the first published Kreyol novel rather than its French avatar.

Best regards,

Asselin Charles