“The Book of Collateral Damage” by Sinan Antoon [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards.

Tara Cheesman is a freelance book critic, National Book Critics Circle member & 2018-2019 Best Translated Book Award Fiction Judge. Her work has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Quarterly Conversation, Book Riot, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, The Rumpus and other online publications. She received her Bachelors of Fine Arts from the School of Visual Arts in New York City. You can follow her on Twitter @booksexyreview and Instagram @taracheesman

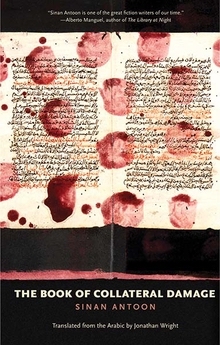

The Book of Collateral Damage by Sinan Antoon, translated from the Arabic by Jonathan Wright (Yale University Press)

The protagonist of Sinan Antoon’s novel, The Book of Collateral Damage, is an Iraqi expat who returns to Baghdad as a translator. Nameer is hired by a pair of Americans filming a documentary. It’s his first time back since his family emigrated to the United States when he was a child.

While in Iraq he decides to visit the bookshops on al-Mutanabbi Street. There he meets a bookseller named Wadood who is working on an unusual project: a kind of catalog of the objects destroyed in the bombings. It includes commonplace items like a handmade kashan, a stamp album and a stone wall. But also a fetus, a Ziziphus (or Christ’s Thorn) tree, and a pair of twins. His stories are often told from the point of view, and in the voice, of the anthropomorphized objects. Structured as colloquies, or “conversations,” they call to mind the Aesop’s fables and Hans Christian Anderson fairy tales. Nameer, intrigued, tries to convince Wadood to let him translate the writings into English. And Wadood, considering the offer, leaves a copy of his manuscript at Nameer’s hotel in an envelope. Nameer takes it back to America with him.

Yoko Ogawa’s The Memory Police, another book on this year’s longlist, is also concerned with the disappearance of everyday things. Particularly the items we most take for granted. In both Ogawa’s and Antoon’s writing the empty spaces left behind are imbued with emotional and cultural significance. In The Memory Police, each disappearance is a loss to the community, but one which most of the community accepts in silence. There is a gentleness to her descriptions, and a tangible sadness. Even if they don’t remember what they’ve forgotten, they remain aware of the act of forgetting. In The Book of Collateral Damage the colloquies are more violent, but no less haunting. Each loss is a complete erasure and the human component, as perpetrators and victims, is surprisingly powerful—even when described by an inanimate object without contextual awareness.

I say “my mother” because I claim that she loved me as if I were her son. I remember how her son used to cry in her arms when she fed me. He and his three brothers. But he’s grown up now. But even so she told him off when he tried to persuade her to get rid of me and replace me. “But this oven is older than you. It has fed you and your brothers since your father died and it has helped pay your university fees. I won’t let it go till I die,” she said. She used to swear by me, saying, “By this oven!”

After returning to the United States, Nameer takes a job at Harvard, and then NYU, teaching Arabic language and literature. He keeps the manuscript. Years pass. He completes his dissertation, falls in love, and remains in contact with Wadood—though the ongoing war and Wadood’s personal situation make it difficult at times to stay in touch. Nameer remains obsessed with translating Wadood’s stories, despite Wadood asking him not to. Nameer has also begun collecting articles and pictures from newspapers about the continuing war in Iraq. He hangs them on his apartment walls in hope they will provide him with the inspiration he needs to write a novel of his own.

The Book of Collateral Damage reads as semi-autobiographical. At one point, Nameer talks about an idea he has for a novel about a young man who washes the corpses of the dead in Iraq—pretty much the plot of Antoon’s 2013 novel, The Corpse Washer. His protagonist identifies with Iraq as his home country, but as an American he is far removed from the actual fighting. The truth is that other than a few insensitive colleagues, and family members who still reside in Iraq but with whom he doesn’t seem particularly close, the war barely impacts his day-to-day life. And, yet, he struggles and cries out in his sleep. He’s often angry and unhappy. He carries the war inside him and his girlfriend believes he suffers from P.T.S.D. As the book goes on we see that the occupation of Iraq has affected Nameer and Wadood differently, but both men carry emotional and psychological damage because of it.

I was going to ask him whether he knew that in Arabic the words for hope and pain were almost the same, with just the two consonants transposed—amal and alam.

Most of what I’ve written so far is plot summary, barely touching on the overarching themes or the translation or how strange it was to be reading this book while I, like other non-essential workers, sit at home in obeyance of stay-at-home orders issued in response to a global pandemic. Antoon is very good at capturing the strangeness (and frustration) of living tangential to, yet still affected by, historical events. Years from now, when someone asks what it was like during COVID-19, what do we say? We stayed at home, took long walks, sewed masks and worried about how to pay our bills. While the men and women in hospitals and grocery stores, distribution centers and manufacturing, public service and food delivery, still went to work every day. Nameer wants to do something, to have some positive impact on what is happening in Iraq, when in reality he is both helpless and irrelevant. He is also aware of the hypocrisy of his position. It’s not all that hard to relate.

Should this book win The Best Translated Book Award? Maybe. If I’m being honest . . . I don’t know. Its chances seem slim, when you consider that I’m writing about it rather than one of this year’s judges. My recommendation is read it anyway. Jonathan Wright’s translation is keen and light. He wisely lets the plot bear the weight, not the prose. It’s a good book. And a good reminder that our present situation is just another blip in the history of civilization. Antoon writes about the Iraq war from a different perspective than we’re used to seeing. Nameer is both Iraqi and American. He is aware that he is in a privileged situation—working for an elite university and living comfortably in one of the most expensive cities in the world. His family remains safe. In one sense, the bookseller Wadood is a thread that stretches between Baghdad and Manhattan, allowing Nameer a connection to a country and a war he feels increasingly removed from. As I said, Antoon writes best about ordinary people caught on the periphery of battle. He does so honestly, without shying away from the truth about his characters or their situations, even when those truths are sometimes unattractive and those situations far outside our ability to control.

I found this book to have depths of story telling, technique, meaning, a showing not telling–letting the reader slowly come to dawning realizations, sometimes to devastating effect. This is the kind of book that makes me sit back and wonder, ‘just how does a true writer’s imagination work to come up something fresh yet in conversation with a rich tapestry of artists from the past. The concept of collateral damage here is profoundly explored. Yes, this book should win, but not by ‘defeating’ the others by some measures of fiction writers, but because it really is quite good, timely, and Iraqi and American novel…the subplot of the narrator’s slowly developing romantic relationship with an African American woman, meeting her mother, eating great food during the dinner she has cooked and serves, I’d think that instead of the narrator being a fish out of water in both his homeland and adopted country, instead the narrator embodies being an Iraqi and an American in some important, complex ways. Oh, back to the review: the narrator at book’s opening is finishing his Ph d at Harvard in Arabic. He moves to teach at Dartmouth.