“Beyond Babylon” by Igiaba Scego [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards.

Barbara Halla is an Assistant Editor for Asymptote Journal. She works as a translator and independent researcher, focusing in particular on discovering and promoting the works of contemporary and classic Albanian women writers. Barbara holds a B.A. in History from Harvard and has lived in Cambridge, Paris, and Tirana.

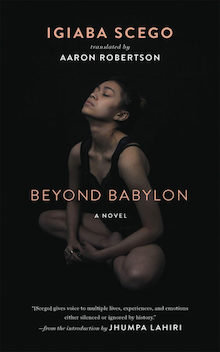

Beyond Babylon by Igiaba Scego, translated from the Italian by Aaron Robertson (Two Lines Press)

“Oh, Mar,” writes Miranda, one of the five narrators of Beyond Babylon, to her daughter, “you have so many cities within you. You represent Venice and also Genoa, Lisbon, Buenos Aires, Mogadishu, Rome.” There is no one-liner that can easily summarize an epic like Beyond Babylon, and while this quote itself might feel useful as a starting point to understanding the book, it can also be misleading.

Like its five main characters, who divide their lives and identities between some half-dozen cities and cultures, Beyond Babylon belongs to many countries, and many eras: Zuhra and Mar, two young Italian women of Somali descent, spend most of the book in Tunis taking an extended course in modern Arabic and both have ties to Spain. Miranda’s chapters take us back to Buenos Aires in the 1970s, at the height of Argentina’s “Dirty War.” And through Maryam and Elias, the reader explores a remembered Somalia through more than three decades of national and personal history, from the years Somalis spent under Italy’s brutal colonial rule, to the first few years of the country’s independence.

It’s a sprawling journey across continents and generations that begins and ends in Rome, the city that all characters have called home at one moment or another in their lives, though Rome is not an uncomplicated home.

And yet, describing Beyond Babylon in these terms would mean to perhaps unfairly categorize it as one of those “global novels” not seldom panned by critics for trying to achieve some sort of universal truth through the medium of literature. It’s true that Beyond Babylon hops from one place to the next, giving us the perspectives of characters at the center of history being made, perspectives often left at the margins of recorded history itself. It is also true that, despite it being written and published back in 2006 (which from 2020 feels like a completely different world altogether), it will strike a nerve with readers today because it is a book that engages directly with issues pertaining to sexual assault, womanhood, race, immigration, and colonialism.

And it couldn’t be otherwise considering the characters that inhabit this story. Zuhra and Mar are both black and Italian and forced to navigate and negotiate their existence in a country that seems to simultaneously despise them and forget that they exist. Zuhra works as a stocker at Libla—a retail chain for books, movies, and music—where she is ignored by white customers who meander the floors looking for someone (white) to help them. Both Zuhra and Mar are always conscious of their bodies not just as women, but as black women, with Mar fielding questions that try to have her explain her existence: “Why are you black, if your mom’s white?” A constant reminder that marginalization entails self-alienation, always looking at yourself how others look at you.

Like all books about displaced people, Scego’s characters are steeped in history, theirs and their ancestors, and much of the book is them trying to make peace with their complicated history. The beauty of this book is that in one way or another these characters are all so humanly flawed, and for all the progressive politics the novel embodies, sometimes personal politics do not quite catch up with their personal feelings. Miranda is an Argentinian immigrant, who escaped Buenos Aires after her brother was kidnapped and tortured by Videla’s regime at the same time that she herself became the lover of one of her brother’s potential torturers. Now a famous poet, people come to her for her opinions on the latest world events.

Meanwhile, Zuhra tries to smuggle her cousins from Italy to Sweden, where she hopes they will be able to find a better and more welcoming new home, and when faced with the ethical questions of what that would entail, she offers this indictment of the system that has forced her into that decision in the first place:

If this meant paying a soul smuggler to drive them around half of Europe, so be it. Was it illegal? No more than it was tossing toxic waste in Somalia or feeding civil wars and insecurities to plunder the riches of African countries as the West did. The word illegal didn’t make sense anymore. Not for me.

But while Zuhra is constantly aware and vocal about a number of institutional and societal ills, that doesn’t mean that she herself isn’t victim to some poor decision-making, chief among which is her propensity to fall in love with sickly-looking white boys who don’t give her the time of day.

Sometimes I fear that talking about Beyond Babylon only in these terms makes it easy to fall into the trap of feeling like Scego has written a book that deserves a prize or acclaim because it checks a number of boxes. That sort of trap leads to looking at the socially relevant aspects of this book at the expense of the intimacy that imbues its pages, not that the two are necessarily mutually exclusive.

Yes, this is a book about capital I important topics, but it’s also a book about the characters’ fraught relationship to their own fragile bodies, to their families, to their surroundings. There is an unvarnished focus on the female body, on how it keeps women alive, and how it can burden them through menstruation and defecation. But it’s not just bodily functions, much of Beyond Babylon is also about pain and pleasure as experienced (or perhaps dictated) by the body: how the characters’ eyes see (or miss) the vibrant colors of Rome and Tunis, the smells of Brava, the taste of familiar food. Look at how Maryam, Zuhra’s mother, describes the all-day feast held in her native Brava to celebrate Somalia’s independence:

They gave themselves merrily, especially that day, in a constant give and take. They filled their mouths with halwa, hot dumplings, fragrant injera, spiced rice, stew. Everything was gulped down with shai and ginger coffee. There were also colorful drinks being passed around, and the children argued briefly over sugared bur.

It’s important to mention that if Beyond Babylon works so well, it is especially thanks to Aaron Robertson’s pitch-perfect translation. Scego has carefully crafted the narrative voice of each character in her novel, they differ in tone, register, in the turns of phrases they use. And you can tell how Robertson has worked just as meticulously to map these differences into English: Zuhra’s tone is scathing and self-deprecating, Mar’s aloof, scared, a person not yet in touch with her own feelings. Miranda’s writing has a poetic yet almost artificial quality to it, as befits a poetess who strives for honesty but isn’t quite there yet. No wonder her section is filled with phrases such as, “Everything is parenthetical in life.” Whereas Maryam, who is trying to dredge up the memory of her past in Somalia to gift it to her daughter, takes often the tone of a parent recounting a messy fairytale, her home “a past that bordered on legend.” And finally, Elias, the only male point of view in this tale, whose pages sometimes read like dense, though no unpleasant, historical treatises.

Language is a driving force in Beyond Babylon which mixes various tongues—Spanish, Italian, Somali and even Arabic. It is languages that bring people together, as Miranda, Maryam, and Elias record for their children the stories they can’t bear to tell out loud. It is also what drives people apart in all that language cannot express, in the barriers that are erected between second-generation immigrants and their parents when the former never quite learn their mother’s tongue under pressure to integrate to a new home. Beyond Babylon raises these issues, while also rejecting the very premise of strict integration and fluency, taking pride in not being one sole, uncomplicated thing. As Zuhra, first reluctantly, then proudly says in the book’s epilogue:

“I don’t speak, I mix.”

Leave a Reply