TMR Season Thirteen: “Ada, or Ardor” by Vladimir Nabokov

The public has spoken, and the next book to be featured in the Two Month Review is Ada, or Ardor by Vladimir Nabokov!

The public has spoken, and the next book to be featured in the Two Month Review is Ada, or Ardor by Vladimir Nabokov!

Which is kind of perfect. We follow the thread of Anna Karenina from The Book of Anna by Carmen Boullosa to this novel, originally written in 1969, which opens:

“All happy families are more or less dissimilar, all unhappy ones are more or less alike,” says a great Russian writer in the beginning of a famous novel (Anna Arkadievitch Karenina, transfigured into English by R. G. Stonelower, Mount Tabor Ltd., 1880). That pronouncement has little if any relation to the story to be unfolded now, a family chronicle, the first part of which is, perhaps, closer to another Tolstoy work, Destivo i Otrochestvo (Childhood and Fatherland, Pontius Press, 1858).

As is pointed out in the “Notes from Vivian Darkbloom” (an anagram for Vladimir Nabokov for anyone not in the know), this is an inversion of the opening line of Anna Karenina: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” And, as you can see in Vivian Darkbloom’s note, that’s just the beginning of the fun Nabokov is having here:

pg. 3. All happy families etc.: mistranslations of Russian classics are ridiculed here. The opening sentence of Tolstoy’s novel is turned inside out and Anna Arkadievna’s patronymic given an absurd masculine ending, while and incorrect feminine one is added to her surname. “Mount Tabor” and “Pontius” allude to the transfigurations (Mr. G. Steiner’s term, I believe) and betrayals to which great texts are subjected by pretentious and ignorant versionists.

And we’re off! But off to what exactly? Vintage’s jacket copy is almost cryptic in its elusiveness:

And we’re off! But off to what exactly? Vintage’s jacket copy is almost cryptic in its elusiveness:

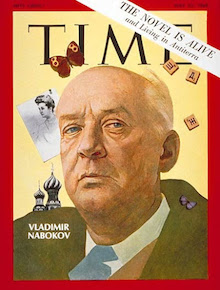

Published two weeks after his seventieth birthday, Ada, or Ardor is one of Nabokov’s greatest masterpieces, the glorious culmination of his career as a novelist. It tells a love story troubled by incest. But more: it is also at once a fairy tale, epic, philosophical treatise on the nature of time, parody of the history of the novel, and erotic catalogue. Ada, or Ardor is no less than the supreme work of an imagination at white heat.

Not terribly helpful, except for the trigger warning re incest . . . The original New York Times review provides both a bit more info, and a source for that jacket copy:

“Ada, or Ardor: A Family Chronicle” (its full title) spans 100 years. It is a love story, an erotic masterpiece, a philosophical investigation into the nature of time. Almost twice as long as any previous Nabokov novel, its rich and variegated prose moves from the darkest to the lightest of sonorities as Nabokov sensually evokes the widest range of delights. Nabokov the lepidopterist once said that he was “born a landscape painter,” and he has never “painted” more luminous landscapes than in “Ada.” It is an extraordinarily visual book, teeming with allusions to painters and paintings, and many scenes are veritable tableaux vivants of works ranging from Beardsley’s illustrations for “Lysistrata” to the idyllic landscapes of Monet and Prendergast. As the family chronicle to end all such chronicles, “Ada” is a kind of museum of the novel, and it employs parody to rehearse its own history.

More specifically, “Ada” is presented as the memoir of Dr. Ivan (Van) Veen, psychologist, professor of philosophy and student of time, who chronicles his life-long love for Ada Veen. The story of the affluent and ingrown Veen family is not a simple one. The novel’s first three chapters are difficult reading and the narrator himself addresses remarks to “the reader.” Two first cousins, “Demon” and Dan Veen, marry twin sisters, Aqua and Marina. On the prefatory Family Tree it appears that Aqua and Demon have produced Van (b. 1870) and that Ada (b. 1872) is the child of Dan and Marina. In fact, however, Van and Ada are the result of Demon and Marina’s continuing affair.

More recently (uh, a decade ago), Garth Risk Hallberg wrote about it for The Millions:

More recently (uh, a decade ago), Garth Risk Hallberg wrote about it for The Millions:

Doing so means reconstructing the history and geography not only of anti-Terra, but also of “Terra” – the mythical “sphere” alluded to above. This mirror-world turns out to be, from our standpoint, nearer to reality, but from the perspective of of anti-Terra, as far-out as Zembla. Who but those wacky New Believers could possibly credit the existence of Athaulf the Future, “a fair-haired giant in a natty uniform…in the act of transforming a gingerbread Germany into a great country?” [. . .]

Aesthetically, intellectually, and even morally, this is a Difficult Book par excellence. It demands a lover’s patience.

Excellent. Sigh. I have a feeling this will end up being the most challenging book we’ve done to date, partially because Nabokov is always four steps ahead of his readers, but also because there are a lot of experts out there who love this book, and we’re just two guys of middling intelligence . . . So if you are an expert (or even if you’re not!) and would like to come on to talk about this book—or Nabokov in general—hit me up. Here’s the reading schedule:

Excellent. Sigh. I have a feeling this will end up being the most challenging book we’ve done to date, partially because Nabokov is always four steps ahead of his readers, but also because there are a lot of experts out there who love this book, and we’re just two guys of middling intelligence . . . So if you are an expert (or even if you’re not!) and would like to come on to talk about this book—or Nabokov in general—hit me up. Here’s the reading schedule:

September 9: Part I, Chapters 1-9 (pgs 1-60)

September 16: Part I, Chapters 10-19 (pgs 61-122)

September 23: Part I, Chapters 20-29 (pgs 123-180)

September 30: Part I, Chapters 30-37 (pgs 181-235)

October 7: Part I, Chapters 38-40 (pgs 236-290)

October 14: Part I, Chapters 41-43; Part II, Chapters 1-2 (pgs 291-346)

October 28: Part II, Chapters 3-6 (pgs 347-395)

November 4: Part II, Chapters 7-11 (pgs 396-446)

November 11: Part III, Chapters 1-6 (pgs 447-501)

November 18: Part III, Chapters 7-8 (pgs 502-532)

November 25: Parts IV & V (pgs 533-589)

December 2: Ada Scholarship

Leave a Reply