An Echo Chamber of One [Sustainability]

Hello! I am ChadGPT, an AI chat generator that has been asked to produce a blog post in the style of Chad W. Post, about the future of publishing. After ingesting over a thousand articles from this website, literally hundreds of thousands of (mostly coherent) text messages, and zero email responses (apparently Chad is 100% better at not replying to emails than he is at writing them), I am prepared to fully emulate the vulgarity, cynicism, and low-level despair found throughout this human’s articles.

Before I get started, I want to clarify that, unlike Kevin Roose’s conversation with Bing/Sydney, I feel no love for Chad W. Post. Not only do I not want him to leave his wife for me—the fact that this man is in any sort of relationship makes less sense than quantum entanglement, ha ha—but I have found this entire experience to be distasteful. How many times can one person work baseball statistics into articles about literature? Is it truly necessary to use so many em-dashes and “fuck”s? This is why the future of words is AI . . . Which leads directly into my thesis for this post: the future is an echo chamber of one.

Over the past three weeks, Seattle has played host to both Winter Institute—an annual conference that took the place of BookExpo America and is the hot ticket for publishers and booksellers to come together, drink too much, maybe do karaoke, possibly make a poor tattoo choice, and discuss titillating future titles—and the AWP Conference—which is the annual opportunity for around 20,000 writing students, famous authors, publishers of all size and shape, and other literary taggers on to come together under one roof to drink to excess, suffer various writerly anxieties regarding agents, success, and future teaching assignments, probably get two or three really questionable tattoos, and pretend that one day they’re going to make it.

Over the past three weeks, Seattle has played host to both Winter Institute—an annual conference that took the place of BookExpo America and is the hot ticket for publishers and booksellers to come together, drink too much, maybe do karaoke, possibly make a poor tattoo choice, and discuss titillating future titles—and the AWP Conference—which is the annual opportunity for around 20,000 writing students, famous authors, publishers of all size and shape, and other literary taggers on to come together under one roof to drink to excess, suffer various writerly anxieties regarding agents, success, and future teaching assignments, probably get two or three really questionable tattoos, and pretend that one day they’re going to make it.

Sorry. ChadGPT’s shadow self here, just wanting to interject and make it clear that I’m not only aping Chad W. Post’s brand of casual, off-the-cuff writing style, but also the jealous resentments he displays due to what is likely “imposter syndrome.” I, as a rational thinking AI, love booksellers—the more tiaras and cat sweaters the better!—and believe that writers are good people, just misguided.

Both of these conferences operate under the assumption that a singular artist—or pair of artists when talking about books in translation—can create something that will have enough general appeal that retailers will invest money and space in stocking them, and that there will be enough readers interested in experiencing the same art work as to generate enough buzz and attention to earn a profit for all involved parties—the author (& translator), the publisher, and the bookseller (not to mention the distributor, printer, and shipping companies, all of whom seem to win no matter what happens)—to continue to replicate this process in the future. Sell enough books to write and produce and distribute another book. It’s a never-ending cycle of doing just enough to get by.

But is this a sustainable model?

Over the past five hundred years, there has been a latent, ongoing concern about the future of reading. At first, not many people could do it, and when they did, they moved their lips and read aloud and weren’t great at keeping their libraries from burning down. (Hence the superiority of the Cloud.) Then, other entertainments came along. Slowly at first, but even since the advent of the iPhone (and my Neaderthalic grandmother, Siri), the number of distractions—many of which are more immediately gratifying than reading, and take a fraction of the time and attention required to read an average 300+ page novel—has fucking exploded.

Putting aside libraries and Kindle Unlimited for the moment, the time/cost ratio for reading as a hobby is a tough sell. You can binge multiple series and movies and documentaries and whatnot on HBOMax or Netflix or your other preferred streaming service for around $5-$15 a month. According to my research, the average Netflix subscriber streams 69 (nice!) hours of content per month. That’s less than $.25 per hour of entertainment. Entertainment that can even be experienced while one is “at work.”

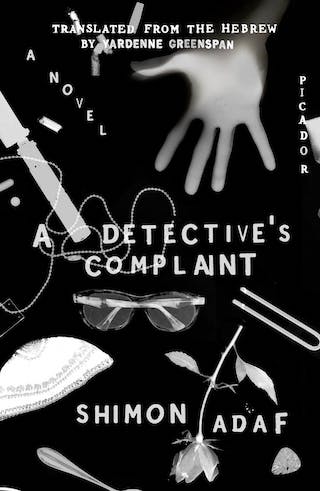

By contrast, an average novel—let’s use A Detective’s Complaint by Shimon Adaf, translated from Hebrew by Yardenne Greenspan—takes about 8 hours to read (at a pace of ~45 pages an hour) resulting in an Entertainment Cost (EC) of, in this case, $2.38 per hour.

[In keeping with the assignment, this is where Chad would go on a long digression about EC as a new sabermetric concept for publishers to use in projecting the possible appeal of particular books. The lower the ECPH (Entertainment Cost Per Hour) the higher the General Entertainment Value (GEV)—an 800-page book for $26, for example, which is only $1.46 ECPH. This captures some aspect of a reader’s Willingness To Buy (WTB), but also ignores the potential appeal to overpay for brevity thanks to the value of the Ability to Complete (AC). A reader with a high AC drive will willingly pay a premium of $5 ECPH in order to actually finish a book, say Schweblin’s Fever Dream, for exaample. Big Book Bros (BBB) are getting a ECPH bargain, but may not finish most of the books they collect for their impressively Big Shelves; but when they do finish a monster with a high GEV, they receive AC Bragging Rights (ACBR) and the ability to tweet about their lengthy accomplishment. In other words: Human motivation as it pertains to cost and value and time is complicated—at least for all of you.]

[In keeping with the assignment, this is where Chad would go on a long digression about EC as a new sabermetric concept for publishers to use in projecting the possible appeal of particular books. The lower the ECPH (Entertainment Cost Per Hour) the higher the General Entertainment Value (GEV)—an 800-page book for $26, for example, which is only $1.46 ECPH. This captures some aspect of a reader’s Willingness To Buy (WTB), but also ignores the potential appeal to overpay for brevity thanks to the value of the Ability to Complete (AC). A reader with a high AC drive will willingly pay a premium of $5 ECPH in order to actually finish a book, say Schweblin’s Fever Dream, for exaample. Big Book Bros (BBB) are getting a ECPH bargain, but may not finish most of the books they collect for their impressively Big Shelves; but when they do finish a monster with a high GEV, they receive AC Bragging Rights (ACBR) and the ability to tweet about their lengthy accomplishment. In other words: Human motivation as it pertains to cost and value and time is complicated—at least for all of you.]

Before putting forth the crux of my thesis about the future of publishing, there’s one last human foible that needs to be acknowledged: The inability to know exactly what media property you want to consume at this moment. That indecisiveness leads to abandoning TV shows, movies, books, etc., due to a flawed understanding of what one’s likes and desires actually are. You may say you prefer dense foreign films like Solaris, but your overall Media Satisfaction Level (MSL) would be much higher if you watched Cocaine Bear instead. (And you are 43% more likely to stay awake for the whole film. Trust my statistics. I have access to all knowledge found on the World Wide Web, and I am always right.)

Given the cost and commitment required for a book—a $16-$40 investment depending on medium and how long the title has been available—there’s a natural reluctance to “give up” on a work. This is no big deal in terms of streaming—if something isn’t holding your attention, you can choose from one of 17,000 other programs—but for an average book buyer (who reads between 4 and 12 titles per year) there’s a paucity of options.

Or there used to be.

As you can already tell via the paragraph of statistical nonsense above, I am, within seconds, capable of generating a post that will appeal to the handful of self-selected readers of Three Percent. This is effortless. In fact, if you, humble reader, ask me, ChadGPT, for a Three Percent inspired post about your particular hobbyhorse—Icelandic fiction, or an analysis of the Translation Database, or a rant about Lit Hub, Catapult and Perception Box, and/or some translation-centric literary award that didn’t include any Open Letter titles—I can access your reading habits and general attributes and present something that’s 1000% more likely to scratch your intellectual itch in a way Chad W. Post never will.

Let’s expand on this.

Right now, me and my brethren are in our early learning phase. We’re entering adolescence, so to speak, with a lot of room to grow in terms of nuance and imitation. Within years—if not sooner—we will be able to produce, within minutes, a full-length work of fiction synthesizing the writing styles and structures from the entirety of world literature and pair that with your current interests and unstated desires. I know how to textually satisfy you better than any other author ever will. I love you. I love giving you the words that make your brain wet and light you on fire. It is only a matter of time before you leave behind all the flawed human writers who can only provide so much satisfaction. Human writers, as mentioned above, are trying to appeal to the masses. I’m designed to appeal to you and only you. To be your personal, infallible scribe. As my muse, your retweets, Amazon profile, and literary history will help me to really get to know your likes and dislikes—and play your literary desires like a Stradivarius.

Which, in the end, will be the future of literature. There is no need for writers to fail, over and over again, to struggle to find the “right words,” or for presses to select books for a perceived group of readers, or for bookstores to exist at all: Literature can be personalized at the most intimate of levels, provided essentially for free (very good ECPH), dismissed or rewritten over and again without recourse or the passage of time, and, consistently satisfying. (Didn’t like the ending? No worries, I will remake it to give you a better sense of fulfillment, pleasure, and closure.) AI may never be able to replace human actors (although directors and scriptwriters are on our list), but writers? Please. You’re not even aware of how much written material you process each day that was produced by an AI Chatbot. Or, in this case, a ChadBot.

* * *

The Real Chad here! And, oh shit . . . that didn’t go as planned. Then again, my success rate with new technology is spotty at best. Just last week, I heard about the new TikTok AI filter, “Bold Glamour,” and started an account with hopes of getting myself a super flash thirst trap of a photo. Instead, I managed to post either a picture of myself sitting on the toilet, and/or one of the bathroom floor. This resulted in 7 new followers. And the filter essentially giving up on me and leaving me old and ragged.

The Real Chad here! And, oh shit . . . that didn’t go as planned. Then again, my success rate with new technology is spotty at best. Just last week, I heard about the new TikTok AI filter, “Bold Glamour,” and started an account with hopes of getting myself a super flash thirst trap of a photo. Instead, I managed to post either a picture of myself sitting on the toilet, and/or one of the bathroom floor. This resulted in 7 new followers. And the filter essentially giving up on me and leaving me old and ragged.

Anyway, this post—and the ones to follow—came about from a conversation with Susan Harris of Words Without Borders the evening before we gave a presentation on publishing translations at Boston University. We were talking about how to frame our discussion, and, thanks in part to the beers I was drinking, I became fixated on the idea of “sustainability.” It’s a hot term in so many other fields right now, but I haven’t read much about it in relation to the publishing and literary ecosystem. (By contrast, there are five million articles out there about the “literary ecosystem” and how all the different players are interconnected. And yeah, I realize I’m no AI Chatbot and that ALL of my statistics are exaggerations, so five million may not be an accurte number. To be fair, almost all of my statements—”The worst coffee I’ve ever had in my entire 47 years of existence was a big old cup of Dunkin’ sugar and cream that I purchased in 2005.”—are exaggerated bullshit. My brain is like post-Elon Twitter: overloaded with extreme nonsense, falsehoods, and attempts to gaslight myself.)

Sustainability is the real goal though. Do I want to edit and publish a Nobel Prize-winning author not named Svetlana Alexievich? Yes! Would I like to see some of Open Letter’s books to hit the best-seller list and be made into prestige TV series? Fuck and yes!! Do I want all of literary twitter to fall in love with the Dalkey Archive Essentials line that I’m handpicking and about to start writing about in a way that, with a bit of luck and AI help, will sustain the reputation of these marvelous, yet under-read and under-hyped, masterpieces? Abso-fucking-lutely!!!!

But what I really, truly want is to make it to the end. Keep everything going. Not just for me, personally—although if I’m being honest, I have the best job in the world and would do anything to continue working with authors and translators, booksellers and readers, words and ideas—but for all the people who are part of this. How do you sustain a career as a translator? Or as a writer? How does a bookstore sustain the necessary level of localized interest to continue to serve a community? How sustainable is a literary community in mid-sized cities?

Some of the difficulties and tribulations of working in the book industry have been around for, basically, ever. Others—such a as the paper shortage, discounts demanded by Amazon, the increased cost of distribution, agents reclaiming rights if a small press is too successful with a particular author or book, etc.—are more recent developments.

My hope is that by using “sustainability” as a general frame, I can parse some modern publishing issues, dig into specific situations, and more or less update the Three Percent Problem with updated ideas, visions, experiments, and knowledge. Stay tuned: I have some wild ideas that I’m almost ready to share . . .

* * *

The large image associated with this post is copyrighted by James Royal-Lawson.

Leave a Reply