Perfect Lives [Reading the Dalkey Archive]

Perfect Lives

Robert Ashley

Original Publication: 1991

Original Publisher: Archer Fields Press

First Dalkey Archive Edition: 2011

Let’s start with the cover.

When this first arrived in the mail, I was certain that Ingram had sent it to me on accident. It looks nothing like other Dalkey covers—especially from that 2012-2020 period of stock photos, usually in triplicate—with its striking full-color photograph and attractive font. It looks almost commercial. And the image itself? It’s like something an art publisher would use to emphasize the performative nature of the text and position it as a book for gallery-goers, for artistes.

Which, after reading the book, is pretty accurate! This is a book that—although it’s from the early-1980s, replete with Nancy Reagan refs—has its roots in 60s counterculture. Without context, you could read it as a sort of extended beat poem set to psychedelic jazz.

In some ways, Perfect Lives is unusual in the Dalkey catalog, being an opera (not sure Dalkey published any other operas) that scans like poetry (reminding me a bit of David Antin’s Talking), reads like jazz music, and begs for the reader to watch it[1] (or hear it performed) in order to really immerse oneself in this little Midwestern world featuring a bank theft, “The World’s Greatest Piano Player,” an elopement, and two old people in love who can’t marry.

Perfect Lives consists of seven acts totaling 146 pages of what looks like poetry. That said, like poetry—or like opera, I assume, and yes, I’ll admit my ignorance and philistine nature now: I’m not very familiar with opera and, as such, am not a big fan, but something about this particular piece has lit my mind on fire—it requires concentration, rereading, zooming in and out, and, again, listening to the almost three-hour long recording.

Perfect Lives consists of seven acts totaling 146 pages of what looks like poetry. That said, like poetry—or like opera, I assume, and yes, I’ll admit my ignorance and philistine nature now: I’m not very familiar with opera and, as such, am not a big fan, but something about this particular piece has lit my mind on fire—it requires concentration, rereading, zooming in and out, and, again, listening to the almost three-hour long recording.

In addition to the text itself, this volume contains a forty-page addendum of bits from talks Robert Ashley gave at Mills College Center for Contemporary Music in 1989 that, honestly, is worth the price of admission by itself. His notes are so unadorned and direct, a fascinating look into how this opera—and the others in the trilogy, Atalana and Now Eleanor’s Idea—were constructed, why certain choices (what he refers to as “improvements”[2]) were made, the collaborative elements of making music, the camera angles and shots dictating the movement of each act, and other amazing observations.[3]

He also provides a concise summary of the core event fueling the opera for anyone lost in the flow:

[. . .] the basic theme was an over-the-hill entertainer and his somewhat younger pal on the Midwest circuit, who find themselves in a small town, playing at the Perfect Lives Lounge, telling stories about the people of the town. They become friends with two local characters, the son and daughter of the sheriff. The four of them hatch a plan to do something that, if they are caught doing it, it will be a crime, but if they are not caught it will be Art. The idea is that the son of the sheriff, who is the assistant to the manager of the bank, will make it possible for them to take all the money out of the bank for one day. And then they will put it back. They’ve set themselves a challenge, but it’s outside the realm of crime; it’s not like Bonnie and Clyde. There’s a kind of metaphysical meaning for the removal of the money.

This event takes place in “Act III: The Bank (Victimless Crime),” but, well, if you’re expecting this to be some sort of wild heist . . . you’re likely to be disappointed. Sure, the money is taken from the bank (and kept in a car that races toward Indiana with Gwen and Ed, who are planning to elope, and Dwayne and The Captain of the Football Team), but the theft (premised upon sound to get into the vault) happens off-screen, and is only discovered in Act III, when Isolde attempts to break up a dogfight in the bank with a bucket of water, but instead dumps it all over the bank manager. Who, for reasons unexplained, yet necessary to making the plot, such as it is, move forward, keeps a spare set of clothes in the vault. So when he goes to change, he realizes the money is gone. “The Bank has no money in the bank.”

Although the crime/art performance is the centerpiece of the opera’s plot, like all real literature, the real pleasures are to be found in the overall construction, the achronistic presentation of the seven acts begging to be put in order, and, most importantly, the poetry itself, which shifts scene to scene and line to line, taking on serious tones, such as these “philosophical” musings on the Self from “Act IV: The Bar (Differences)”:

The Self is without coincidence, being

The only thing the Self.

The Self is without attainment,

Being perfect.

[. . .]

And we said the Self is ageless being

What I don’t know.

The word eternal is a mystery to me.

I don’t understand that word.

to observations about supermarkets made by an old couple who fell in love in an assisted living home (“it’s different being old alone and being old / together”), yet can’t marry without losing their benefits:

it chooses its manifestation

it makes a mistake it chooses the mirror this

supermarket is stupid this supermarket wants itself

in the form it finds itself this supermarket has

some problems imagine yourself can of succotash in hand

part of th’material body of the supermarket in the

checkout line you are about to be exhausted

symbolic writing fills the skies ufo’s link to

weird animal mutilations (p)age eight Cher

my strange relationship with Sonny centerfold how

to make your life more meaningful (p)age fifty-two how

to make your marriage more exciting (p)age thirty

to this incredible bit that literally made me laugh out loud, spoken by the sheriff as he “solves” the “crime” in “Act V: The Living Room (The Solution)” through a strange verbal ritual with his wife:

[. . .] in

this theory the important element is (quote) the opportunity (unquote).

f’r instance, only yesterday i decided for myself: no more incidental music.

as soon as i made this plan, the phone rang. the voice said:

there’s money in it for you. i restrained myself from saying:

hot diggity. instead i said: oh, boy,

i am totally, exclusively, completely’n only into—

as they say—song. Who’s gonna write the words?

the voice said: well, what we had in mind was something more abstract.

i said: do you mean as in music that supports action that is

unexplained? the voice said: yes. i said:

do you mean i find music from my own motives, and while that music is performed

people in costumes will jump around on stage?

the voice said: that’s more or less the idea. i said:

fuck you man. next time you’re in the bathroom, hang yourself. that’s

what i mean by the element of (quote) opportunity (unquote).

to the understated final line (spoiler?): “I’m not the same person I used to be.”

*

Given the disorder of the seven acts—which take place first at 11am, then 3pm, 1pm, 11pm, 9pm, 5pm, 7pm—and the fact that most all of the poetic lines are unattributed, well, and, the lack of a traditional “cause begets effect” plot, and the slippery, abstract poetic nature of the writing (and the music itself! and the experimental television broadcast!), Perfect Lives probably comes across as a rather daunting read. But if there’s one message I want to get across over the whole of my life, it’s that great literature (and great Dalkey Archive titles) will open up and explain themselves to you—if you have the patience and mental openness to let them.

Ashley is clearly a genius[4]—I can’t wait to listen to the other parts of this operatic trilogy, and to revisit Perfect Lives in all of its forms, including the special performance by Matmos [INSERT LINK] of a few acts, an all-time favorite band [INSERT LINK]—but he’s also incredibly Midwestern in terms of approachability and the desire to tell stories.

And that’s what Perfect Lives really is: a series of stories about connected individuals.[5]

Which is what most Dalkey Archive titles are as well. Stories about people conveyed in ways that tend to dwell on and elevate the form of the telling of the story instead of its content.

*

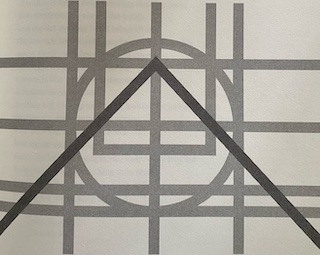

Which leads me to one last note about the form and structure of Perfect Lives, namely, this symbol, which precedes every act:

Related to each act, a certain motif in the symbol is highlighted. (See the near triangle formed from the darker lines in the image above.) Based on Ashley’s notes,[6] I believe this stems from how they visually arranged the television production, with each act focused on a particular line or set of lines that stands in for the movement of the camera.

The camera movement is explained in the table of contents which, very helpfully, sets the scene and illuminates the general motion. For example, here’s “Act II: The Supermarket (Famous People)” (the symbol for which is pictured to the right):

Helen and John, who live at The Old Folks Home and have a strange “arrangement,” are shopping on their day off. Thoughts on consumerism and wearing out. The landscape is a large Midwestern supermarket. Lines converge at the horizon in the distance. The camera zooms in. 3 pm

As a non-reader of poetry, cues of these sort go a long way to transforming a text from “daunting” to “enjoyable.” Although maybe that’s actually my big takeaway when it comes to Perfect Lives: I opened the book expecting to be flustered and dismayed, having to double-down to “make sense” and find anything worthy of sharing, publicly. It took an intro (which we’ll publish soon) and the opening line—“He takes himself seriously”—for me to find myself just giving in and letting the text itself guide me.

[1] This opera was produced for London’s Channel Four and broadcast in seven parts over the course of a week. It’s never aired in the U.S.—to the best of my knowledge—but some brave, and likely bored, soul, uploaded all of it to YouTube in 2020, during the pandemic.

[2] “There is an instant, right before you play the chord, where you decide to will that chord into existence. It’s not the piano that does it, it is you. You go . . . [plays chord] . . . and then you have to accept what came out. Now, having made that first move, the next thing you have to do is to decide whether to keep it, or improve on it. Now, if I’m going to improve on it, I have to apply a whole range of social opinions, including Nancy Reagan’s opinion. Everybody is involved in whether I’m going to improve on what I just did, or whether I like what I just did. If I like myself, I actually have to like what I just did. And that’s what makes you original.”—Robert Ashley

[3] “At the time we were engineering Perfect Lives, I would go into the studio in the evening, and by the time we’d got the studio set up it was time for the reruns of All in the Family on television. I’d never seen All in the Family. I mean, I knew who Archie Bunker was, but that was all. So, every night I’d watch it just before we’d begin work on Perfect Lives. You know, I’d be eating my sandwich and drinking a Coke and watching All in the Family. And I thought, this guy is doing very crude operas. It’s just like Perfect Lives: There are the two kids, there’s the middle-aged guy, and there’s the world’s greatest piano player—his wife.”—Robert Ashley

[4] “It seems to me that when I hear people doing the most interesting thing for them to do, in the most exotic realms of popular music—I’m talking about people like Michael Jackson—the most important thing he is doing is he’s trying to break down that time. He’d trying to shatter the grip of that symmetrical time, without going into 5s and 7s that cannot be put together easily. You can’t stay out there on the stage for two and a half hours if everything is going 4/4, it makes you crazy. You have to think of a way that it’s interesting for you spiritually. Otherwise you might as well be driving a car.”—Robert Ashley

[5] “Perfect Lives is just the great Midwest, and no story has a beginning or an end. It’s all digressions.”—Robert Ashley

[6] “We divided the screen into seven equal bands vertically and six equal bands horizontally. The templates in that geometry were a way for us, as musicians, to communicate with the visual people. I had the idea that for each episode there would be a characteristic camera movement, a dynamic, and the camera dynamic would be illustrated graphically in a pattern on the screen.”—Robert Ashley

Leave a Reply