Mulligan Stew [Reading the Dalkey Archive]

Mulligan Stew

Gilbert Sorrentino

Original Publication: 1979

Original Publisher: Grove Press

First Dalkey Archive Edition: 1996

“Cheers!” So this may be the first—but definitely not the last—entry in this series that is kind of weird.

First off, unlike the earlier posts, which try to say something semi-comprehensive about the book in question, this one is more of an invitation: I want everyone who reads this to join along with the landmark 20th Season of the Two Month Review podcast and read Mulligan Stew with us throughout September and October. (And maybe a bit into November. Our idea of “months” and “time” is a bit slippery.)

Additionally, as TMR progresses, I’m going to be adding to this post every week. This may take the form of quotes, short analysis, info from outside sources, whatever. But in the end, it will be a chronicle of reading Mulligan Stew, rather than a static, singular post.

Anyway! Let’s dig in! Five reasons to read Mulligan Stew:

1) Sorrentino’s Reputation.

Gilbert Sorrentino is a foundational Dalkey Archive author. Actually, more than that, he’s like the literary father figure that the press’s catalog aspires to impress. He was one of John O’Brien’s aesthetic mentors, and a very close friend who was instrumental in the foundation of the Review of Contemporary Fiction and the press as a whole. (I think they came up with the name “Dalkey Archive Press” together.) The number of stories I heard about “Gil”—even though Gil was no longer speaking to John at the time, which, gulp, yeah, I totally get—could fill volumes. I heard about how Gil didn’t have any depth perception, thus fuck metaphor. I heard about the people who lived in the apartment complex that was the setting for Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things, which was the Novel of Dismissive Mean-spiritedness that John latched onto.

Gilbert Sorrentino is a foundational Dalkey Archive author. Actually, more than that, he’s like the literary father figure that the press’s catalog aspires to impress. He was one of John O’Brien’s aesthetic mentors, and a very close friend who was instrumental in the foundation of the Review of Contemporary Fiction and the press as a whole. (I think they came up with the name “Dalkey Archive Press” together.) The number of stories I heard about “Gil”—even though Gil was no longer speaking to John at the time, which, gulp, yeah, I totally get—could fill volumes. I heard about how Gil didn’t have any depth perception, thus fuck metaphor. I heard about the people who lived in the apartment complex that was the setting for Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things, which was the Novel of Dismissive Mean-spiritedness that John latched onto.

Sorrentino’s career was long and varied, seeing that he experimented with form and the possibilities for fiction with each and every book. There may well be a “Sorrentino Voice”—a bit sardonic, sharp observations, exacting in terms of how language and fiction function—but I’m hard pressed to think of a particular style or approach that would define his career. If you talk to a half-dozen Sorrentino fans—all of whom would be more qualified than I am to write this—you’ll end up with an array of both “best” Sorrentino books and suggestions of “where to start” with his oeuvre. Splendide-Hôtel —a remarkable meditation of sorts, akin to Gass’s On Being Blue—is a great starting point, although Aberration of Starlight might be the most emotional, and most straightforward in terms of the formal experimentation. Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things might be the funniest—and filled with the most daggers—and The Sky Changes is the book everyone should read when they’re preparing for a divorce. Steelwork is unparalleled in how it captures the ins and outs of a particular Brooklyn neighborhood, and Crystal Vision does something similar, but using the tarot as its framework. Gold Fools is a novel in all questions, and, well, Mulligan Stew (my personal favorite and the only of his books with its own Wikipedia entry) is a complete blast from start to finish.

2) It’s a Book about Writing a Book.

The most Dalkey of all Dalkey tropes! But in this case, rather than focusing on the difficulties of figuring out how to write a book, Mulligan Stew revels in the generative nature of creation, spilling forth list after list, joke after joke, opinion after opinion. It’s like Flann O’Brien on crack, with a touch of the movies covered on the How Did This Get Made? podcast.

Here’s the set-up, as simply as I can put it: Antony Lamont is an experimental writer who has never really received the attention he (thinks) he deserves for his novels. But this new book he’s working on? This is going to be the one. A “new wave murder mystery” narrated by the killer, that merges detective fiction and high literature. And is populated by characters he’s borrowed from James Joyce, Dashiell Hammett, etc., etc. (Antony Lamont is a reference to Flann O’Brien’s At Swim-Two-Birds)—characters who, when Lamont isn’t paying attention (aka, actively writing about them), they’re exploring the half-written house they live in and the nearby town, seeking a way out of this horribly written book. In addition to excerpts from the “novel in progress” and the characters inside, we get to read Lamont’s increasingly unhinged correspondence with his sister (especially about her husband, his literary nemesis), a professor who maybe wants to teach one of his books, a poet he’s trying to get into bed, and so so much more.

3) Myriad Forms That Dissect the Nature of Writing.

Although there are certain recurring bits, a big appeal of this book—for me at least—is its diversity of forms, aping everything from detective novels to erotica to epistolary novels to surreal plays to . . . And in each instance, Sorrentino via Lamont manages to expose the quirks and flaws and oddnesses at the limits of fiction. Things that conventional novels coax us into ignoring are presented so baldly in this novel in a way that’s funny and aesthetically captivating.

This will become more and more apparent over the course of this season of TMR, but here are a few fun little quotes to whet your appetite.

First, this is from the front matter, which is a series of rejections of the novel Mulligan Stew:

Dear Gilbert Sorrentino:

It’s wonderful of you to think of us here at New Views Press as possible publishers for your new novel, MULLIGAN STEW. Wow! as my seven-year-old says, all too often, six hundred pages sounds like something! When you say you worked on it almost four years, I can well believe you!

I’m afraid my “batting average” at second-guessing “the Boss” is somewhat less than 1.000 right now, but I’ll go “out on a limb” and risk telling you that it seems very doubtful that we can even consider taking it on, “alas”!

I’m sure you’ve read the newspaper “stories”—albeit many of them were predictably exaggerated—on the dolphin-training project that L was deeply involved in and that came, unfortunately, “a-cropper.” L was rather upset, partly because of the money loss involved, but more importantly, because he hoped to publish an anthology of “Dolphin Poems,” translated by Dr. Mullion Blasto. You can imagine what a “blow” it was to L when Blasto went with Disney. But enough of our troubles!

At the moment, as above noted, I would venture a tentative guess that L simply could not think of publishing such a work as yours. We are still “picking up the pieces” here. I take the liberty of wishing you and yours well, and of extending L’s good wishes to you.

To “good letters,”

John Cates

Managing Editor

Next up, a poem from Lorna Flambeaux’s The Sweat of Love:

Next up, a poem from Lorna Flambeaux’s The Sweat of Love:

“Hot Bodies”

Hot bodies entwined together

stuck with sweat, the gorgeous guck of love.

We fuck . . .

—all unashamed!

Proud of our . . .

Hot bodies!

In my laughing flesh lies hidden

that dark inferno, Life’s secret Word.

It yearns to reach out and whisper

to your smold’ring core. It CANNOT! It CANNOT!

So you, beloved, in my widespread loins must find

the entrance to this deep and tender Word.

YES!!! YES!!!

Only the dead

say “No” to love. Our hot bodies—are aflame

with Life! And now your Life plunges

to my thrilling deeps . . . OH!!!

. . . I swiftly swoon . . .

And here are some of the clichés a group of cowboy characters have been subjected to by hack writers over all the books they appeared in;

In one job I threw my clothes on at least twenty times.

My interest slackens when I’m forced to watch the smoke from my cigarette curl lazily in the air.

Especially when it’s blue smoke . . . and it’s always blue smoke!

But how often have you thoughtfully knocked out your pipe? Or filled it?

If I stretch luxuriously one more time . . .

Right! But how do you feel about your eyes scanning the horizon?

That’s as bad as not liking it because it’s too quiet.

How many times, I pray you, have you emerged into the sunlight blinking?

Not as many times as I’ve grabbed for the phone.

I once had a position where I wheedled every third page.

I was once dazzlingly insouciant to the point of nausea.

I’m damn sick of getting home and going straight to bed without washing.

I’m just as tired of the sun in my eyes always waking me up.

How do you like the wet streets that shimmer in the fog? I’m up to here with them.

I don’t mind the women whose bosoms heave—unless they crack their gum. Or chew it furiously. Or simper.

I was in a scene once with a woman who primped and simpered. As a matter of fact, I think she also whimpered.

As long as she didn’t whine . . .

4) Incredibly Funny.

I think this is obvious by now, but damn, this book is just delightful. Sure, it’s about a writer’s mental breakdown and mental illness is no joke, but holy shit, I dare you to read this book and not laugh. Even the mathematical paper that’s inserted in here (what isn’t included?) is funny in a certain light.

I think this is obvious by now, but damn, this book is just delightful. Sure, it’s about a writer’s mental breakdown and mental illness is no joke, but holy shit, I dare you to read this book and not laugh. Even the mathematical paper that’s inserted in here (what isn’t included?) is funny in a certain light.

But truly, this is a masterpiece of comedic literature. Again, it’s like Extreme Flann O’Brien, or maybe a bit like a contemporary Tristram Shandy. It’s a giant book, and one that does raise—and answer—certain questions about fiction and the craft of writing (this is one of Sorrentino’s “writer’s writer” sort of books), but it’s a book that truly entertains on every page. There are bits—often crass or crude—that function more like traditional jokes, but most of the humor arises from the voices—also frequently crass and crude—found throughout, especially Antony Lamont’s which is soooooo self-serious at times, frequently cringey, and increasingly more and more batshit.

5) Bad Writing Is So Good.

It’s really hard to pull off, but intentionally bad writing is so rewarding to read. Just like really bad movies can be so fun. I used to spout off about—at every logical opportunity—a “theory” I had about art that ~95% of it is devoutly mediocre: technically competent, fine enough, but basically just average. And instead of wasting time on those sort of middling movies or books, I only wanted to read the truly amazing, and the absolutely awful.

And in Mulligan Stew, you get both!

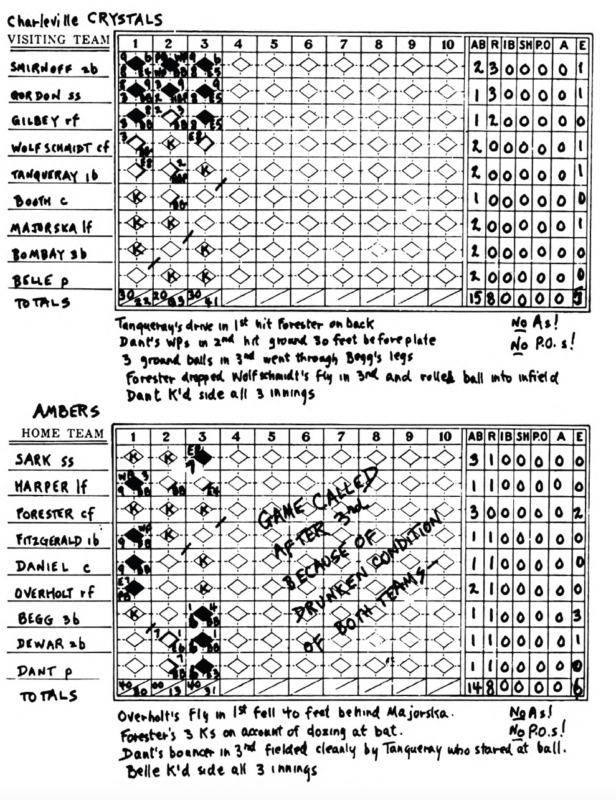

Bonus: There’s Baseball In It.

Just a moment to insert the scorecard of the baseball game Sollis took me to. Whatever it means! It has a certain arcane beauty to it, though. A conversation piece if I work at a decent job soon? I showed it to Ned just before he left and he glanced at it and laughed long and loud.

*

Again, this book is a one-of-a-kind tour de force that is very re-readable, and a great entryway to the Sorrentino world—I’m looking forward to rereading, and writing about, so many of his books over the next couple years—and I can’t wait to dig into this with my TMR cohost, Brian Wood (author of Joytime Killbox and a forthcoming novel featuring a character whose persona and writing would be right at home in Mulligan Stew), a number of guests, and, hopefully, all of you.

Buy a copy of the book, follow along with the reading schedule, and enjoy this season!

Leave a Reply