Publishing Strategies of Rediscovery

A few years ago, New Directions reissued three Clarice Lispector books (and one never-before translated one) with covers that combined into one giant portrait.

Although it was preceded by the publication of a new translation of The Hour of the Star—by Ben Moser, who had recently written an all-encompassing biography of her incredible life—and followed by the award-winning publication of her Complete Stories, translated by Katrina Dodson, it was really this moment, this four-book project was the moment that brought Lispector back from the dusty corners of used bookshop and academia where she had been residing for a while. Suddenly, all these books I (and many, many others) had read with awe in college, the titles of which no bookseller seemed to recognize, were being touted by Buzzfeed and the like as THE publishing event of the year.

Although it was preceded by the publication of a new translation of The Hour of the Star—by Ben Moser, who had recently written an all-encompassing biography of her incredible life—and followed by the award-winning publication of her Complete Stories, translated by Katrina Dodson, it was really this moment, this four-book project was the moment that brought Lispector back from the dusty corners of used bookshop and academia where she had been residing for a while. Suddenly, all these books I (and many, many others) had read with awe in college, the titles of which no bookseller seemed to recognize, were being touted by Buzzfeed and the like as THE publishing event of the year.

A couple years later, Coffee House Press released a similarly designed set of four Brian Evenson books featuring three reprints and a new collection of stories.

Brian Evenson is a goddamn star, and you could do much much worse than to spend the next couple months reading all four of these titles. And although he has a huge number of fans, and receives a good deal of critical attention, it would be dishonest to claim that the rediscovery of these three works got anywhere near the same amount of buzz as the Lispector.

Brian Evenson is a goddamn star, and you could do much much worse than to spend the next couple months reading all four of these titles. And although he has a huge number of fans, and receives a good deal of critical attention, it would be dishonest to claim that the rediscovery of these three works got anywhere near the same amount of buzz as the Lispector.

Not that one would expect the same sort of publishing strategy to have similar results—the social interests in the two authors are different, the audiences for both overlap yet are distinct, and the marketing reach for the publishers isn’t exactly the same—but it’s interesting that they both tried a similar sort of “four books at once, as a set!” approach. It’s bold, yet makes a good deal of sense. If one book takes off, you’re going to see a really nice halo effect.

It’s not entirely dissimilar from what FSG did with the three books in Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach Trilogy. Although instead of putting out all three books at once, they spaced them out over a seven-month period—a sweet spot in which those who wanted to binge weren’t left wanting, and yet a 250-page book every couple months didn’t feel overwhelming.

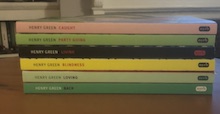

Another author who’s been rediscovered recently (and who has seemingly been published as many times as The Bible) is Henry Green. Back before I was at Dalkey, Penguin Classic had issued a few volumes of his work. Loving/Living/Party Going were all in one volume, Nothing/Doting/Blindness in another. Two solid three-in-one volumes of these books that are the literary equivalent of housing a bucket of popcorn at an Avengers movie—once you start reading, you just keep going and going and going.

When I was at Dalkey, we reissued Blindness, Doting, Concluding, Nothing . . . and maybe another one? We did this at the pace of a book every six months, with the idea that every publishing season we’d have another chance to convince the most prestigious critics and review outlets to do a long rediscovery piece on Green. It never really happened (I was in charge of marketing, so that’s probably on me at least to some degree), and the book sales were never more than modest. But Green is a fucking master, and his books need to be in print so that future generations of readers can stumble upon his novels and learn more about the craft of writing in two novels than they could in most workshops.

That’s the impetus behind Dalkey’s quixotic mission, the justification for its being a nonprofit, and its willingness to keep in print books that—for most anyone else—would be so deep in the red that the symbolic capital would have to be weighed in gold to make them worth publishing.

About ten years later, New York Review of Books reissued a stack of Henry Green titles, with New Directions bringing out Concluding around the same time. (That part I’m still not sure I understand, but whatever.) NYRB brought these out in a few batches, a couple every few months, with a much more condensed schedule than Dalkey, but still spaced out a bit.

About ten years later, New York Review of Books reissued a stack of Henry Green titles, with New Directions bringing out Concluding around the same time. (That part I’m still not sure I understand, but whatever.) NYRB brought these out in a few batches, a couple every few months, with a much more condensed schedule than Dalkey, but still spaced out a bit.

I hope this project has been successful for them. I love Henry Green and NYRB, but it’s hard to imagine how you would market a “rediscovery of an underappreciated master!” who is rediscovered every few years. There’s a reason he needs to be rediscovered every so often; baked into that statement is the fact that he’s never popular enough to remain discovered.

*

The idea of rediscovering forgotten classics, or finding authors who had a book or two out back in the 1950s, but are unknown to readers born since the end of the Cold War is such an interesting publishing conundrum to me. On the one hand, for a young press to reissue a famous author who has fallen out of favor is a smart move–if the author has enough fans, you gain that symbolic capital and maybe your target audience gets interested in your entire publishing program. (See: Our reissuing of Elsa Morante’s Aracoeli along with Marguerite Duras’s The Sailor from Gibraltar followed by the first-ever translations of L’amour and Abahn Sabana David.)

There’s also an impulse to introduce these younger audiences to the foremothers and fathers of the writers they’re currently gushing over. (Literary lineage is usually restricted to the canonical, by which I mean the male and the academic. That’s boring. There are hundreds of authors working from 1940-1980 who have dropped off the map, but would still feel revolutionary and inspiring if you read them today.) To recapture what the market deemed “unfashionable,” but which deserves to have a resurgence of interest every generation.

It doesn’t make any sense to believe that every book is published at its right time. This is for a different post—it’s coming, they’re all coming—but success in the literary world is predominantly due to luck, and given all the moving parts in the publication and promotion and reception of any given book, what are the odds that it happens to ship to stores on the date that’s most advantageous to all of that working in unison? Given the impossible odds layered into that last sentence, why shouldn’t a book keep coming back? Why shouldn’t an author be “rediscovered” time and again until the moment is the right moment for the right size of right readers?

*

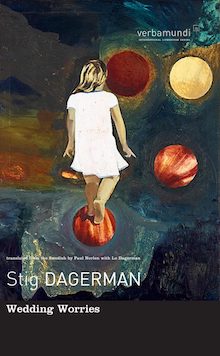

All that is a long prelude to talking about Stig Dagerman’s Wedding Worries, which is just out from David R. Godine. It’s the thirty-first book in the Verba Mundi series from Godine—an incredible collection of authors that includes Donoso and Perec—and is part of a multi-year rediscovery effort of Stig Dagerman’s works.

Because that’s another way that authors who have passed on, or whose literary cache has drifted, can be rediscovered: book by book, patiently.

Wedding Worries by Stig Dagerman, translated from the Swedish by Paul Norlen with Lo Dagerman (David R. Godine)

(The coloring on that image is way the fuck off. I only say that in case you go looking for this on a bookstore table and see something much more stylized with a very maroon/brick-red stripe across the bottom—it’s the same book! Godine’s site has this non-cover, but all the images of the correct cover online are too small to put up here.)

I won’t be surprised if readers of this blog have heard of Dagerman; I won’t be surprised if no one reading this has heard of Dagerman.

I’m no expert on Dagerman’s life, but I remember coming across Island of the Doomed back in early 2012 shortly after the University of Minnesota had reissued it. Before that, it had been published by Quartet Books in 1991.

If you know Quartet Books—and I mean the old school Quartet, not this new version with their twenty-five title backlist and fancy graphics—you know that a) they had a fucking incredible list that included Heimito von Doderer’s The Demons, Inesco, Krleža, Pirandello, Boris Vian’s Heartsnatcher, E. M. Cioran, and more, and b) the materials they used for their covers was so stiff it would cut your hand. Also, their uniform look—reminescent of the earliest, earliest, gray-and-overdesigned-and-numbered NYRB titles—went out of style with U2.

But Dagerman had been published by Bodley Head in 1959, which was only a few years after he passed away at the age of 32, having written four novels, a collection of stories, hundred of poems, some plays. Thirty-two. In 1954 he died in his garage with the car running.

I might be missing something, but based on WorldCat and Wikipedia, none of his major works—major should be in quotation marks there—had been translated into English before he died.

How do you rediscover a modernist mid-century master who—again, I might be projecting or straight up full of shit here—has never really found his English-language readership?

*

Slowly is an option.

Quartet Books did a couple things in the 1980s and 1990s.

University of Minnesota did German Autumn, Island of the Doomed, and A Burnt Child between 2011 and 2013.

Godine has brought out Sleet (2013) and Wedding Worries (2018).

Is this enough momentum? What allows an author who can’t tweet, who can’t give readings, who can’t parlay his charms into reviews to be rediscovered?

*

Having just reread Fox by Dubravka Ugresic, one thing that really jumps out at me about the Dagerman situation is the impact that Lo Dagerman, his daughter, has had on his career in English. In Fox there’s the Widow who cultivates Levin’s career, building him up (maybe from nothing at all!) into a literary superpower. There’s the narrator wondering who will take care of her works when she’s gone. Lo Dagerman is that figure writ large.

At least five of her dad’s works have made their way into English thanks to her efforts. (I’m assuming, and I doubt anyone will tell me I’m wrong.) There have been events. Literary coverage. She told Godine to send me this book because she knew I liked Island of the Doomed a whole lot. Because we’re friends on Facebook and she likes my dumb posts once in a while. Every author who was ahead of their time needs a Lo; every author with a Lo will have some serious longevity.

*

By the time you’re reading this, you likely know that it was announced that I am receiving this year’s Ottaway Award for the Promotion of International Literature. In my world, this is literally the highest honor I could ever receive. It’s granted by Words Without Borders at their annual gala, and their past winners is a who’s who list of people I admire and wish to emulate. The whole thing is surreal. The biggest honor I’ve ever received, or dreamt of receiving.

(One anecdote because once I get going on these posts, I can’t stop writing: When I first started at Dalkey Archive, I had to go back to Grand Rapids, MI for some holiday. While there, I went back to Schuler Books & Music—the first bookstore I ever worked at—with my now ex-wife. We bought too many things, we saw all our old friends. And I remember walking through the fiction section and dreaming that someday, as illogical as it might be, I would do something so great for translations and experimental literature that I would have a reputation. A nickname. An award. THAT HAS HAPPENED AND DO YOU KNOW HOW INSANE THAT IS?)

(A few years later—sorry, can’t stop, won’t stop—I was in NYC trying to convince publishers to sign up for the Reading the World program promoting 20 translated titles in over a hundred indie bookstores across America. It was a democratic program to a fault, that was also a small ripple in the tidal wave that Words Without Borders and Archipelago and PEN World Voices and everyone set in motion re translated fiction. But. BUT! I went into the offices of Knopf and met with Paul Kozlowski, RIP, which will make me cry because he was so much of an inspiration, about getting Knopf, KNOPF, on board with this weird promotional idea that was coming out of a small nonprofit centered in Normal, Illinois. At that point in my life, I had been to NYC maybe a half-dozen times. Maybe. I didn’t dress right or know the right people or understand where you were supposed to eat or drink. I was a lost midwestern boy who thought books mattered more than anything else in the world. And PK, PK was the best. So warm, so inviting. [Years later, he helped Kaija work on her pitch for the book she’d translated while at a BEA party for Other Press. That’s who he was. That’s what it means to me to be a good literary citizen and, more than that, a good person. But now he’s gone and Karl Pohrt of Shaman Drum—also part of the Reading the World Brain Trust—is gone and the world is worse off.] He agreed to put Knopf’s weight behind the program—which included things like Europa Editions (when they were brand new) and 2004 New Directions and Archipelago—which blew me away. I left that building feeling like I had just won a gold medal. I remember, so distinctly, being 28, on top of the world, thinking I have just helped change the way we talk about translated books like I an arrogant LAX bro, and then getting on the subway and feeling uncomfortable. It took a couple stops—and many people fleeing the car—to realize I was sitting next to a guy carrying a bag of laundry that smelled like piss. Flaubert would make this ironic, Knausgaard would dwell on the anxiety of my momentary hubris, I just remember thinking: Not everyone cares about books.)

I have so much more to say about WWB and this award, but I will save it. I just want to leave by saying that the day it was announced, all I wanted to do was go home and work on this. Thank every single one of you who tweeted at me or liked a post or texted me. You all make me want to cry. It’s still too much. There are dozens of people who deserve this award. DOZENS. Dozens of incredible people who are helping to change the world, to open up readers to voices and viewpoints, to make this whole translation industry run. I love you all. You’re why I like to goof around in these posts—to entertain you because you’re what makes this worthwhile. All the editors, publishers, booksellers, readers, Twitter handles . . . You are the ones who prove that the idea of publishing international literature is something worthwhile. Thank you.

*

Wedding Worries is an incredible book. I urge you to stock it, buy it, read it, recommend it. It’s on the level with The Governesses and Pretty Things and Fox and the other handful of amazing books I’ve read this year. LeClezio, who is all over the Dagerman books, refers to his fascination with reading Dagerman slowly, comparing it to Ulysses and Light in August, all of which sounds like blurb-speak at first glance. But this is the most Faulknerian book that I’ve read in years. Dagerman is a master of voices, of speakers, and of how to hide and show crucial information.

A simple retelling of the plot: Hildur Palm is going to marry the butcher Hilmer Westlund in a tiny rural Swedish rural area.

More complicated retelling of the plot: The entire novel takes place over the course of one day as someone—a former lover? a tramp? both?—knocks on the bride’s window in the wee hours, spooking everyone and setting in motion a day as out-of-hand as a Krasznahorkai novel (Satantango comes to mind) and as funny in a characters-are-unaware-of-their-shortcomings way as any Faulkner novel. It’s fucking brilliant.

I know you know the game of these posts is that I talk a lot about books without talking about the book, and this post will be no different. I won’t tell you what happens in Wedding Worries because I want you to have that experience. My students will in the spring because this is definitely a book I’ll be including in my world fiction class.

There’s so much to like here, so much giggling and joy amid the pure run-down, dissolute, messed-up set of characters and desires. The brother of the bride believes he can win over a bartendress from town with his well-polished rake. This is not a metaphor? It’s not a joke. He even breaks it—drunk—in a fashion that impress his lady. You will never have this rake. THAT IS SO HOT.

The main takeaway—and I will end this with a quote to give anyone sticking with me through all of that a bit of relief, a bit of joy—is that the book doesn’t tell you when it’s being funny. When we meet the butcher, he seems flush with cash, with respectability.

By the end of the book, he’s lost full control of his slaughterhouse—and all of the subservient positions—his pants (I might be misremembering), his wedding ring and that of his wife (TOTALLY TRUE), and most of his other possessions. How? Poker. Because you can’t stop won’t stop.

There are deaths and fake deaths. Moments when you realize no one understands their place in the world and that’s funny. A rivalry among sisters that includes a scene in which one of their sons—born out of wedlock, very young—sprays them with water and wants to BURN IT ALL.

*

This is a book every cool bookseller I know—every one of you Winter Institute kids—would love the shit out of.

If four of his books—A Burnt Child, Island of the Doomed (one of the weirdest books I have ever read), Sleet, and Wedding Worries—came out as a set from New Directions? You would lose your collective fucking minds. This would be every staff pick (LOOKING AT YOU BRAZOS) and you’d be pointing to it as a parallel to Chronicle of the Murdered House.

*

Pay attention. You might miss tomorrow’s today by not paying attention to yesterday.

*

Setting: Poker game.

Players: Westlund, the groom and butcher who is a braggart; Simon, his rival who also won his business, via cards; Bjuhr, who takes EVERYTHING from both of them because wedding and drunk and nope.

Then Simon opens with a two-crown coin, tosses it into the bottom of the wooden bucket. Bjuhr places his cap on the bottom, so the bills won’t get wet. [I don’t understand these physics.] At the end of the game he puts his cap on, the bills tucked into his sweat band, the silver and copper jingling in his pants pocket.

“A person should’ve had a profit margin,” Westlund says, business-like.

“Profit margin? It’s better to take home the profit all at once.” So Bjuhr takes it home, whistling. Off-key. A bicycle built for two. But you should be be careful biking with him.

“If the post office was open,” Westlund says, “a person could withdraw money from the bank. In America you’ve got your debentures of course.”

*

Do children relate to pre-Internet books?

*

I wanted to write a section about when Knausgaard became popular. Was it the James Wood review about volume one? And if so, is “Ferrante vs. Knausgaard?” (or whatever) from the New Yorker the peak? How will volume six be received? Will anyone care? Will they care more? (I’ve gotten nothing but dismissiveness and despair from friends whom I’ve told about my plan to read this final volume.)

Here is a picture of where I am in volume six.

I have things to say, but the Cardinals just won, so I’ll save them. I am struggling though. This book can not fit in hands.

[…] Worries by Stig Dagerman, which is another book that I wrote about earlier this year and which I hope makes the BTBA […]