A Rat, a Labyrinth, “Ah Library TNT”?

What makes an Oulipian book Oulipian?

Because my outline for this Deep Vellum post is approximate 17,000 words long, I’m going to condense my planned opening into eight bullet points. If you’re not familiar with the Oulipo or their literary program, here’s a quick-hitting introduction:

- Read this book by Warren Motte or the Oulipo Compendium;

- According to Wikipedia—the world’s favorite reference source—the Oulipo is “a loose gathering of (mainly) French-speaking writers and mathematicians who seek to create works using constrained writing techniques.”;

- Constraints are predetermined rules that the writer has to abide by, things like the “prisoner’s dilemma” (no letters that have a tail or a stem can be used, so no “t” or “p”), a lipogram (elimination of a particular letter or letters, such as Perec’s A Void, which lacks the letter “e”), or something like n+7 in which every noun in a piece is replaced by the seventh following noun in the dictionary;

- There’s also this book by one of the youngest members of the Oulipo, who was also a guest on the Three Percent Podcast (which I called “A Gin & Tonic Does NOT Make Me a Better Oulipian” for reasons left to history and a blurry past);

- Check out the “inner circle” of Oulipian writers and books: Life a User’s Manual by Georges Perec (so many constraints! starting with the “knight’s tour” and a cutaway of an apartment building), all of Raymond Queneau but also especially Hundred Thousand Billion Poems, Harry Mathews’s Cigarettes (I still haven’t processed Harry’s passing, and can’t bring myself to read his last book yet because I avoid grief and ideas of death at all costs; and yes, I did get really drunk with him once and asked him to tell me what the secret was behind “Mathews’s Algorithm” and he laughed), and If on a winter’s night a traveler . . . by Italo Calvino, and The Great Fire of London by Jacques Roubaud;

- Oulipians are “rats who construct the labyrinth from which they plan to escape”;

- Look into the back catalog of Dalkey Archive Press (Jacques Jouet!!) and/or Deep Vellum for more recent additions to the Oulipo, including, in the case of DV, the first Spanish and Argentine members, about whom I’m about to say things.

The Anarchist Who Shared My Name by Pablo Martín Sánchez, translated from the Spanish by Jeff Diteman (Deep Vellum)

Quick Summary: This is a novel about the anarchist Pablo Martín Sánchez, who committed suicide after being arrested for trying to invade Spain in 1924 and ignite the revolution against Miguel Primo de Rivera. The author Pablo Martín Sánchez discovered the “anarchist with the same name” by accident and, according to his prologue at least, researched the shit out of the anarchist and pieced together this 580+ page depiction of his life.

Oulipian Constraints: Nothing stood out to me. Sure, there are two alternating threads to this novel—one starts in 1924 and goes through the “incursion” into Spain and Martín Sánchez’s death; the other tells the story of Pablo’s life from birth through 1924, eventually overlapping with the opening to the novel and its “present tense” narrative. It’s almost a sort of Möbius Strip, although not exactly, and not to the level of complexity of Cortázar’s Hopscotch. There has been a debate among members of the Oulipo as to whether the constraints they use to construct their fictions should be made evident in the course of reading the book itself (see: A Void), or should be invisible, like scaffolding that helped in the construction of a structure—a structure that now stands by itself with no need for scaffolding at all. Although there’s a fun, speculative ending to the book that semi-usurps the previous 500+ pages, this isn’t explicitly Oulipian, except insofar that Martín Sánchez is part of the Oulipo, thereby making everything he writes “Oulipian” in at least one sense, since the Oulipo is first and foremost a writing group.

Martín Sánchez’s Oulipian Pedigree: From Oulipo.net via Google Translate (all errors and spacing issues exactly as from Google Translate): “in Spain, he co-founded the journal Ludolinguistics Verbigràcia , sponsored by the oplpian Màrius Serra, and began preparing a doctoral thesis entitled The Art of Combining Fragments: Hypertextual Practices in Oulipian Literature (Raymond Queneau, Italo Calvino , Georges Perec, Jacques Roubaud)he will finish a few years later at the University of Lille, under the co-direction of Christelle Reggiani. [. . .] He has been working since 2002 on a project called The Project ( El Proyecto), inspired by the Places of Georges Perec, which should end in 2026.” He’s also translated both Alfred Jarry and Raymond Queneau into Spanish and was officially elected into the Oulipo in 2014 as the first member from Spain. New-lipian! Viva la España!

Other Thoughts?: This is fun to read! Sure, it’s looooonnnggg, but aside from a few middle sections where the alternating narrative chapter structure forces the book to drag a bit, it reads faster than you’d expect, and has the same compelling sort of plot-driven narrative as a great Dickens novel. Also, there are anarchists and revolution and when are those things not fun to read about? All historical names and contexts are explained in non-pedantic ways that give the average reader all the necessary information re: Spain pre-World War II.

The Imagined Land by Eduardo Berti, translated from the Spanish by Charlotte Coombe (Deep Vellum)

Quick Summary: A Chinese girl growing up in the 1920s and 30s meets another girl, Xiaomei, who she thinks is just the most beautiful, amazing girl in the world. They become friends and develop a touching relationship that is disrupted by the arranged marriages of the narrator and her brother. (Who she was trying to set up with Xiaomei.) It’s a small novel that captures that moment in which you leave adolescence and when things can still feel monumental in a very hopeful, open-eyed way.

Oulipian Constraints: Again, I might be missing something. It’s a nicely constructed book with interstitial sections of the narrator talking to her dead grandmother in her dreams, but it’s not explicitly “Oulipian” in a Queneau/Roubaud/Perec sense. I think all twenty-six letters appear.

Eduardo Berti’s Oulipian Pedigree: Will’s bio on Deep Vellum’s site is fine, but this Oulipo.net one is way more fun to parse (again, all errors are [sic]): “Eduardo Berti has been a member of the Oulipo since June 2014. Born in Argentina in 1964, a Spanish-speaking writer, he is the author of several short stories, a book of small prose and several novels. Translator and cultural journalist, it is translated into seven languages, in particular in French language where one can find almost all his work [. . .] not to mention two texts difficult to classify: Small Mirrors and Retrospective Bernabé Lofuedo .” First Argentine member of the Oulipo! Viva La Albiceleste!

Other Thoughts?: This is the sort of book that I usually don’t read—really straightforward, rather emotional, mostly plot-driven—but that I greatly enjoyed. Charlotte Coombe is a translator I recently became aware of via her translations for Charco Press (soooo jealous of their covers), but this is the first one I’ve read. I liked it! There were one or two word choices that stood out—always in occasions when I remembered this was set in 1920s China—but otherwise the voice is really consistent and compelling. The one thing that troubled me—and which I’m not sure how to explain in a way that’s both “yay The Imagined Part!” and “yeah, I’m woke!”—is the potential trouble of an Argentine male writer depicting the life of a fourteen-year-old Chinese girl from almost one hundred years ago. There is a proliferation of superstitions and rituals and beliefs and traditions (like taking pet birds to nature to keep them singing, about not getting married within two years of a major family death, etc.) in this book that, if they’re not part of a larger Oulipian constraint/construct, raise some issues about whether they’re in the stereotyping or cultural appropriation side of things, or an accurate historical representation. I’m not sure how this will play with critics, but I hope people read the book either way. It sort of doesn’t matter that it’s a Chinese girl at the heart of the novel—the heart of the book is the tender descriptions of the relationship between the two girls. Sure, if you set this in Argentina, it would diminish the “cultural exploration” aspect of reading a translation, yet wouldn’t actually matter that much. In an alternate-reality Argentina, there are arranged marriages and people grow up and apart. That’s still sad and something every human can relate to. Still. I won’t be surprised to read a critique of this book from that particular perspective. There’s a lot more to mine than I’m capable of unpacking.

*

In honor of the Oulipo—and these two titles being the fourth and fifth Oulipian books Deep Vellum has published—I thought I would do my own P+7 Oulipian experiment. Listed below are the seventh books (as listed in the Translation Database) published by a variety of small presses. What does this say about the presses? No idea. Nothing, probably.

The Journey by Sergio Pitol, translated from the Spanish by George Henson (Deep Vellum)

YES! Great start to my LitHub + Oulipo list! Pitol is a cornerstone of Deep Vellum’s list, having published Pitol’s incredibly influential “Trilogy of Memory” with a short story collection (Mephisto’s Waltz) forthcoming. Also, George Henson hates Two and a Half Men, which is, without exaggeration, one of the worst sit-coms ever made in the history of television. Fuck you, CBS.

Rupert by Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer, translated from the Dutch by Michele Hutchinson (Open Letter)

Not what I was hoping for! But, that said, we almost did this at Dalkey—the first third is fucking incredible—Deep Vellum did a different Pfeijffer book, there’s a story about how Pfeijffer posed naked for an author photo because he said that was the only way to get people to buy a book of poetry, and Michele is a really good person and translator.

False Calm by Maria Sonia Cristoff, translated from the Spanish by Katherine Silver (Transit Books)

I remember Adam and Ashley pitching this at last sales conference, and given the highlights—nonfiction, Spanish, Katie Silver, Transit—I’m shocked that I haven’t thought about this since. Given the overwhelming popularity of Transit titles, I half-expect a bookseller (hello, Sparks, this is so much your jam) to be raving about this on Twitter next time I open the app . . .

Proposed riverside theater site part of $250M high-rise hotel and retail complex https://t.co/eZlofILjCt pic.twitter.com/jPSnngX1HB

— Democrat & Chronicle (@DandC) October 23, 2018

Oh! The most recent Tweet on my timeline is about Rochester’s Parcel 5! That’s sooooo surprising!I hope they open the world’s largest Abbott’s there and create a custard-cream swimming hole in the middle of Rochester’s most famous parking lot.

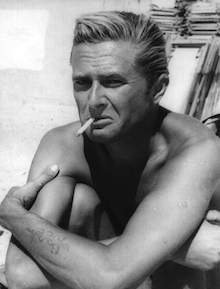

All Backs Were Turned by Marek Hlasko, translated from the Polish by Tomasz Mirkowicz (New Vessel)

Perfect. This is a classic NV author. Just look at this dude!

Also, I have to say, this is saved on the NV website under “Ufberg-image.” I LOVE YOU ROSS. In a different reality—where I don’t waste my nights watching rich baseball teams approximate regular season baseball for nineteen hours a night—Ross looks just like Marek. NO! CHECK THAT! Ross lives Marek’s life.

“Marek Hlasko, known as the Polish James Dean, made his literary debut in 1956 with a short story collection. Born in 1934, Hlasko was a representative of the first generation to come of age after World War II, and he was known for his brutal prose style and his unflinching eye toward his surroundings. In 1956, Hlasko went to France; while there, he fell out of favor with the Polish communist authorities, and was given a choice of returning home and renouncing some of his work, or staying abroad forever. He chose the latter, and spent the next decade living and writing in many countries, from France to West Germany to the United States to Israel. Hlasko died in 1969 of a fatal mixture of alcohol and sleeping pills in Wiesbaden, West Germany, preparing for another sojourn in Israel.”

I’m pretty sure Ross told me a story once about how Hlasko was living in L.A. to make a movie of one of his books, but then punched out the director and quit the project. That’s a thing.

Buy New Vessel books. Please. Just do it.

The Secret of the Water Knight by Rusalka Reh, translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire (AmazonCrossing)

Katy Derbyshire was the first ever Three Percent fan I ever met. I can’t remember the name of the conference I was at, but it was in London and during one of the events I sat next to A. S. Byatt’s daughter (also named Antonia? She was maybe the head of PEN England back like a decade ago? My memory . . .). Anyway, after the event ended, a pleasant young woman came up to me—with her mother—and asked if I was “the” Chad Post.

Katy is a wonderful translator and, despite all of her work, feels really underappreciated in a general sense. We should all go buy one of her translations this week—either the one mentioned above or one of the nine she’s done for Seagull Books—and support someone who does quality work but doesn’t try and push into (or accept being pushed into) the spotlight all the time.

The Game for Real by Richard Weiner, translated from the Czech by Benjamin Paloff (Two Lines)

Two Lines has a great look to their books. (gibbons) Their covers are both classy and of the moment. (gibbons) They have Ben Paloff—who mostly (?) translates from Polish—working for them. (gibbons) They do things that are too edgy for the National Book Award (BADGE OF FUCKING HONOR), yet strike a (gibbons) chord with a lot of readers. Two Lines is a place of experimentation (gibbons) and trendy (gibbons).

Sorry, Michael, I can’t keep our in-j0ke going! I love you all, and hope you gibbons a gibbon gibbons for gibbons gib gibbonish gibbonsy gibbons gibbon. XOXOXOX

Like a New Sun: New Indigenous Mexican Poetry, edited by Víctor Terán and David Shook and translated by people (Phoneme Media)

I’m 99% sure no one is reading these words. Given that, I want to say two things: 1) the fact that the seventh Phoneme book is about indigenous poetry is the best coincidence given David Shook’s interest, intent, and amazingness and 2) we’re co-hosting an Indie Press Night in L.A. on 11/4 with Unnamed (Phoneme’s sister press). Again, assuming no one—especially not in the L.A. region—is reading this, I feel super comfortable offering a space at the Clayton’s Prosecco and appetizer and free indie press book night to the next four people who email me. I’ll be SHOCKED if anyone contacts me. Also: BUY THIS BOOK. PHONEME ROCKS.

Leave a Reply