Why Are Meritocracy [Two Castilian Books]

I have two books that I want to talk about this week, and one related publishing/cultural issue, but before I get into all of that, I thought it would be interesting to dig a bit into some of the data from last week’s “Spain By the Numbers” post.

As I mentioned in that same post, over the course of this month, I’m going to look at books from Spanish authors in all four commonly spoken languages: Spanish (Castilian), Catalan, Galician, and Basque. Already have two more interviews in the works and some other surprises, but as a bridge between the interview with Katie Whittemore and the publication of her excerpt from Sara Mesa’s Four by Four (coming Thursday!), I wanted to zero in on the most popular Spanish language—Spanish!

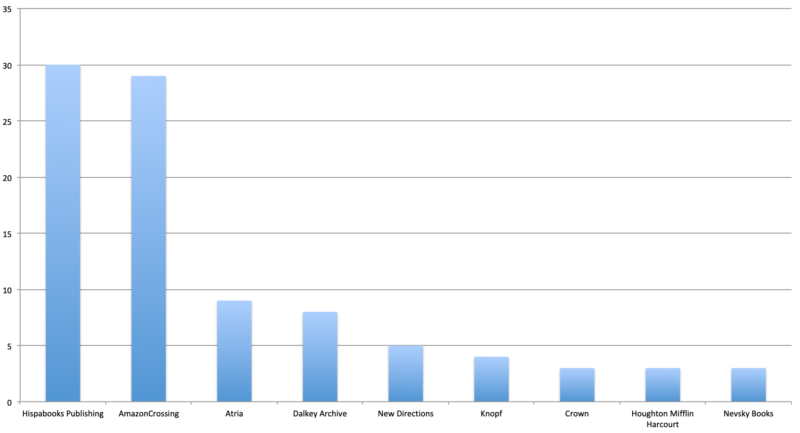

Going back five years (to when Hispabooks arrived on the scene), here are the publishers who have translated the most works of Castilian fiction.

This is . . . weird. Nevsky Books? Four commercial presses? And a press leading the way that, according to all rumors and online evidence, seems to have shut down permanently. (I haven’t reached out to Hispabooks for comment, and as such, they haven’t had opportunity to reply, so if I’m totally wrong about this, I apologize. But I’m keeping my joke from the year-end post no matter what the truth is! And besides, the fact that their last tweet was August 8, 2017 is not encouraging.)

Not to overstate the potential impact of this, but Hispabooks accounted for 22.9% of all Spanish-language books from Spain published in translation over the past five years. That’s a remarkable resource to just suddenly lose . . .

I know 2019 is Chad’s Year of Living Optimistically (or, as Brian likes to call it, “Being Sweet Chad Instead of Salty Chad”), but the fact Hispabooks struggled isn’t necessarily that surprising. They were based in Madrid, trying to sell their books into the U.S. market without a strong marketing presence here. And although they got a solid amount of love from the usual bookselling/reviewing suspects—the Mark Habers and Veronica Espositos—and worked with truly top-notch translators—Lisa Dillman, Sophie Hughes, Peter Bush, Nick Caistor, Margaret Jull Costa, on and on and on—I’m curious as to how many of their titles you heard of.

I could be wrong, but I suspect Paris by Marcos Giralt Torrente, translated by Margaret Jull Costa, is the book that got the most play here in the States. Torrente was also published by McSweeney’s the year before Paris came out, and in a translation by Katie Silver, which likely made a difference.

By contrast, most all of you own one of the Javier Marías books that Knopf did. And some of ND’s Enrique Vila-Matas titles.

New year, same refrain: It’s hard to get attention and sales for a book if you don’t have a number of things working for the title and the press. One of the things that will forever bug me re being on panels with commercial presses is their almost flippant way of declaring how easy it is to sell translations. I’m sure it is . . . for them. But if we want to talk about promoting international literature in an honest way, we have to acknowledge the privilege that commercial presses don’t even notice that they benefit from. (I won’t draw that parallel any more, since I don’t really want to conflate it with far more important social issues, but the way these advantages are obfuscated or ignored by the Big Five isn’t dissimilar from the way certain groups don’t acknowledge the advantages they have because of society’s shitty history and shittier power structures. #EndPoliticalRant)

The main point is that it’s 100% impossible to believe that the cream naturally rises to the top when it comes to literature. Doing the best books isn’t enough. Which brings me to the two books that I want to write about this week: Scar by Sara Mesa and Out in the Open by Jesús Carrasco.

Scar by Sara Mesa, translated from the Spanish by Adriana Nodal-Tarafa (Dalkey Archive Press)

This was—hands down, no qualifiers necessary—one of the three best books I read in 2018. It came out back in 2017 and had been pitched to us a couple years before that (and two years after we were pitched Four by Four, and this is a moment to reiterate that publishing is haphazard and serendipitous and inefficient and based in personal encounters), but had totally slipped by my radar until Katie Whittemore recommended Mesa’s work at Bread Loaf.

This is also—guaranteed, no doubts in my mind—a book that will become a cult favorite among the international fiction set. Possibly because this post will spark the right six people to read it and recommend it to every customer ever (not actually very likely), or because Dalkey will figure out how well this book speaks to the current #MeToo moment and have the right person in place to get that message out there (also fairly unlikely?), or because Four by Four and Cara de pan will take off and people will seek out her backlist (most likely option, I think).

To back up option one a bit: Rodrigo Fresán is a fan of hers and emailed me congratulations the day after we signed her on. That carries a lot of weight for some of us.

Here’s a quick summary of the book: A young woman working a dead-end job gets involved with an online literary community. Following a rather depressing in-person meet-up that she goes to, she starts getting a lot of personal messages from Knut (named after the fascistly famous Nobel-Prize winner, Knut Hamsun), a guy about her same age who excels at shoplifting. He starts sending Sonia books, a sort of one-on-one crash course in the classics. Then he starts encouraging her to write her own stories. That’s followed by more intimate gifts—from perfume to bras to shoes to a hideous, expensive jacket.

Although Knut never asks for anything sexual in return for his gifts (just the cost of posting them), the power dynamic evident in their relationship is wicked fucked up. Privy only to Sonia’s perspective, we get to see her struggling with all of this—trying to break things off at times, enjoying it fully at others, hiding the gifts from her husband, struggling with what it all means and what to really do.

The way in which Mesa lets Sonia be a participant, complicit in this increasingly toxic relationship adds so much depth to the book as a whole, something that’s definitely reflected in the melancholic ending . . .

One thing that I particularly loved though—beyond the increasing tension of their interactions and the attraction toward and repulsion of the two of them becoming a couple, which, now that I’m typing it, is maybe another level of complicitness in this novel, a level in which the reader, working with all the typical “will they, won’t they” schemas, struggles to know how they want the book to resolve itself—was the way the book invokes a number of time loops. Chapter “Zero” is basically the climax, with chapter “One” taking place “Seven Years Before.” Almost every chapter contains a header placing it in a timeline: “Four Months Later,” “One Year Before,” “Three Months Before,” “Three Years Before.” By giving us glimpses into the future—such as when Knut calls Sonia when she’s in bed with her husband, causing her to flip out on him—the book creates a unique sort of narrative momentum. Most of the jumps forward in time have a sort of bleakness to them, a feeling of regret, a sense of dismissing the import of this relationship, etc. And then when we go back, we can’t immediately see how things progress from A to B. It’s a rather masterful way of building suspense and interest. This is far more of a page-turner than you might expect.

*

So why did this book sell (this is an estimate, and I will try and get the BookScan numbers), approximately 1/20th of the number of copies of Out in the Open by Jesús Carrasco, a totally fine book, but not nearly as powerful or approachable or emotionally charged or fascinating as Mesa’s? Why don’t the best books float to the top?

*

Initially, I was going to name this post “Why Are Offseason.” I had the idea—which I haven’t given up on—of titling every one of these weekly posts “Why Are XXXX” and using whatever crazy shit is on my mind that week as the comic relief most of these posts need.

A.K.A., I can’t stay serious for a whole post. I spend like three hours when I should be in bed having a few beers while writing these, and if I don’t have at least something to make the posts weird, funny, or uniquely framed, then I get really bored. If it isn’t baseball, my attention span is garbage.

So, offseasons. They suck! The second the World Series ended, all I wanted was for spring training to begin so that I could believe in my team again, and see how everyone progresses, while downloading new Fangraphs leader boards on the daily and trying to figure out what team strategies are being successfully employed.

And the second the longlists for the 2018 National Book Awards for Translation were announced I couldn’t wait for the 2019 ones to be available. This is similar to how I play sports games on the PS4: As soon as I realize my team lost, I want to fast-forward to the year in which I can experience success. If you don’t have a book on the longlist, or a team in the World Series, then just hit “Simulate the Offseason” and get this shit going again.

Yes, I know my anxiety about age and time should make me want every offseason to go super-slow—how many do I actually have left? twenty? twenty-five? never enough—but I also desperately want that rush of the magic, special, victory-laden season. Sports are dumb, but they’re helpful in giving you something out of your control that you can emote with. The St. Louis Cardinals will never listen to my ideas about pitcher deployment (keep Reyes and Wainwright and C-Mart in the bullpen, and unleash them with Andrew Miller—the pitcher my 2016 Twitter bio is secretly referencing and who is now a Cardinal #swoon—and Hicks to shorten games and strike out everyone. Also, don’t sign Bryce Harper. He’s a 4 WAR player max and will be an albatross come year six of his dumb contract.), but when they win, I personally feel like the day is a little bit brighter.

Right now, I’m just in a holding pattern . . . I know we all need an offseason to process and develop and produce, but it would be so much better if it were suddenly March 27th, AWP was in full swing, and the Cards were facing off against the Brewers.

Out in the Open by Jesús Carrasco, translated from the Spanish by Margaret Jull Costa (Riverhead)

Quick summary: A young boy has run away from home, probably because the bailiff in his struggling town—this is set in a near-future unnamed Spain that’s crippled by drought, with all farmland becoming an abandoned, dangerous place—has been sexually abusing him and other boys. The future is violent and hard to endure. He meets an old goatherd who helps him evade those who are chasing the boy. The goatherd dies, but not before killing the bailiff and all his minions.

It’s a bleak book, written in a style that’s both sparse and sometimes overly formal. It’s like Marías doing The Road. (There’s a log line for you.) But in the end . . . the tension is artificial, there’s not enough about the social-climate collapse to make the world-building work, and it’s 195% predictable. (What percentage is the number that’s finally too far? 250%? 400%?)

It’s a second-rate version of Mercè Rodoreda’s War, So Much War. The biggest difference is that Rodoreda’s novel is in the first person “I lost my way and didn’t know which direction to take, until a carriage road jumped out in front of me, so to speak, and I followed it” and involves a mysterious war; Carrasco employs a mysterious collapse of all rural spaces and the third-person “He was heading north in the middle of the night, trying to avoid any existing paths.” One is emotional, one is stylized in a way that creates a sterile distance from the characters.

One is a masterpiece; one is a contemporary book that’s entertaining, and may or may not be remembered in fifteen years.

*

Instead of comparing Carrasco to a LEGEND, let’s compare him + MJC to Mesa + Nodal-Tarafa:

Sonia interprets his reaction as jealousy. She understands it but feels attacked. So, she attacks in return. She resents lessons on independence from someone who lives with his parents, who doesn’t work, who doesn’t do anything. She resents him accusing her of being opportunistic because what she feels for Verdú is authentic. She resents that he trivializes the antiwar protests when hundreds of innocent people are dying. Or is he in favor of war? Does he not care about the killing of children? The images of their small bodies, completely ravaged, appear in the news every day. How can he be insensitive to that?

Knut’s perfectly organized, point-by-point response follows.

And then, Carrasco:

“Be very wary of the people in the village.” Each time the donkey stumbled, the boy would wake, pondering the old man’s words with a mixture of disquiet and satisfaction. He didn’t know if the goatherd had said this because his own life depended on him returning with the water or simply out of a desire to protect him. Then his neck would droop and his head would once again fall onto his chest and he would again become lost in the magma of his thoughts and memories. The hole he had dug, the palm tree, the poultice, the goatherd’s penis, the arrow slip, the bailiff’s cigarette ends.

Both of these passages were chosen at random (admission of how much I suck at structuring my arguments for these posts), but point toward why I like the Mesa much much more. The ending of Carrasco’s paragraph is supposed to provide a series of images from earlier in the book to serve as “momentous” call-backs for the reader. But in the third person, and in such a direct way, they are simply that. They’re written for the audience.

Whereas with Mesa, that paragraph advances from emotion to emotion in a way that (I assume) we’ve all experienced. We come much closer to the characters and the text and feel less manipulated and more in contact with something pure.

I will always choose raw over too-carefully-crafted.

*

At this moment, on Amazon.com, here are the sales ranks for these two titles:

Out in the Open: 935, 970 (hardcover), 1,520,731 (paperback)

Scar: 1,972, 621 (paperback)

Ouch. OUCH.

Quick: What do you think the 100th best-selling book at 10:39 EST on 1/7/19 is?

. . .

. . .

. . .

Give yourself a pat on the back if you picked The Hive Queen (Wings of Fire, Book 12) by Tui T. Sutherland.

The world’s great. Books are great. The best ones rise to the top . . . over time. Moby-Dick. Just remember Moby-Dick.

*

Why did Out in the Open outsell Scar? A RANKED LIST.

Scar wasn’t really available in the U.S.

This is the sort of “Dalkey dig” that might get my ass in trouble (again), but I was literally just texting with Jeremy Garber of Powells in Portland about how fucking excellent this book is and he told me their orders for it never arrived. And it’s available in one library in Oregon—that doesn’t do interlibrary loans.

Jacket copy might actually matter.

Would you buy this?

Sonia meets Knut in an online literary forum and begins a long-distance relationship with him that gradually turns to obsession. Though Sonia needs to create distance when Knut becomes too absorbing, she also yearns for a less predictable existence. Alternately attracted to and repulsed by Knut, Sonia begins a secret double life of theft and betrayal in which she will ultimately be trapped for years.

Me neither. I can’t write about literature at all, but my description above is more selling.

No one knows Dalkey anymore.

Again, running risks here, but after my last post, and after conversations at MLA, and after the rumor that the main employee at Dalkey has stepped down, it’s hard to pretend that this incredible press is still part of book culture. I know people who are working at very prominent presses, who are keyed in and brilliant, and have never read a Dalkey title. This is an issue. And if Dalkey actually has an active board, you should call me at my home phone so that we can talk about the future, instead of getting all pissed because I’m right.

Fuck both covers.

Happy 2019 Chad or not, these covers are dumb. Please no more color mosaics. And given how much I hate my shitty Apple computer, I totally don’t want to see it on the cover of a book. Hey, here’s a novel about how my spacebar rarely works!

MJC is a known quantity.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with Adriana Nodal-Tarafa’s translation. Her intro isn’t 247%, but it’s OK. A little too Dalkey-indebted and I never like when a translator says that they took out “inappropriate” phrases and word choices. That makes me anxious. Too often they confuse the character for the author, and that reminds me that students don’t actually read anymore.

That all said, there are at least 25 people who buy books based on the translator and not the book itself. Giving Carrasco an advantage.

Blurbs bum me out.

This list got weird, and I apologize for that. But seriously, every review of Out in the Open has the tone and insight of someone who’s read four books from Spain . . . ever. Hyperbole is only useful if you can legit back it up. But then again, this is America, and celebrity > expertise > Tebow.

Also, I won’t quote examples publicly because I want all those places/people to say insanely over-the-top things about our books. But if you want to slide into my DMs . . .

Why don’t we read more books by women?

Again, not really an objective criticism, but given all the #ReadWomen and #WITMonth stuff PLUS PLUS PLUS the fact that there aren’t many books in translation written by women, readers should be all over these titles. But, I can assure you, that, aside from Rodoreda (and mainly just the one title), our books by men sell way better than the ones by women, and in general, receive more attention. I have no explanation for this that doesn’t make me want to shoot myself and/or remind everyone to read Kathy Acker.

Things’ll be different in 2019! ALL POSITIVITY ALL DAY. And Ha Seong-nan. Who. Just wait. Open Letter has so many gems up its sleeve. Or, in my parlance, new pitches to debut that will induce a lot of missed bats. Or swing plane adjustments to hit more dongers? Whatever. Those metaphors . . . Is it baseball season yet?

[…] like with last week’s post, I want to kick off this mini-survey of a couple Catalan titles with a chart of the presses who […]