“Space Invaders” by Nona Fernández [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards.

Chris Clarke grew up in Western Canada and currently lives in Philadelphia. His translations include books by Ryad Girod, Pierre Mac Orlan, and François Caradec. His translation of Marcel Schwob’s Imaginary Lives was awarded the French-American Foundation Translation Prize for fiction in 2019, and his translation of Nobel Prize winner Patrick Modiano’s In the Café of Lost Youth was a finalist for the same award in 2017. He is currently retranslating a novel by Raymond Queneau for publication in 2022 (NYRB Classics).

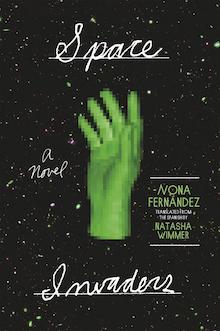

Space Invaders by Nona Fernández, translated from the Spanish by Natasha Wimmer (Graywolf Press)

How do memories differ from dreams? Sure, dreams are all jumbled up, built of slivers and shards, and their combinatory narratives, if they can even be called that, borrow from any perception, experienced or not. They aren’t to be trusted. Memories are supposed to be more concrete, more linear, more factual. But are they? When I think back to my youngest years, I have few memories, and of some of those I can recall, I have since grown suspicious. I remember a great weeping willow in front of our house when I was first learning to ride a bicycle. The bike was red and white with a long banana seat. I feel pretty certain about that one. Even earlier, I remember a hobby horse of sorts, colorfully painted with spots of blue and red on white, which I received one Christmas morning. And yet, while going through old albums during a visit back home, I came across the photograph that lies at the root of that memory. I no longer believe I have a true memory of the horse, or of that Christmas morning, but instead, my mind has incorporated the details of that photograph into its reservoirs and has constructed a memory from its details. Add to these uncertainties other memories that are surely the result of being told a story about my own childhood repeatedly, and it becomes hard to tell what is memory and what is instead internal literary or cinematic construction.=

Space Invaders was Nona Fernández’s fourth novel, first published in Chile in 2013. She has since published two more. Another in a growing list of stellar translations by Natasha Wimmer, Space Invaders is a labyrinthine investigation of how collective memory is formed during large-scale traumatic events. Fernández presents the layered and fragmented recollections of a group of young classmates during the “politicide” years of the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile. Like their memories, the timeline of the narrative is fragmented and inconsistent: the children are about ten years old, and it is about 1984; the children are no longer children, but in their early forties; or, they are about twenty, around the time the media announced the legal rulings on the Caso Degollados, the “Slit-Throat Case,” bringing the grisly murders back into the public eye. Whether ten, twenty, or forty years old, their thoughts are always focused on that same time period, seeking to construct sense from what they remember, what the evidence tells them, what they have since learned and unlearned.

People remember things in different ways; my wife almost always remembers her dreams, and she seems to have detailed memories of her childhood in a way that I don’t. This variability of memory is evident among Maldonado and her friends, as well. Not only in what they remember, but in how they remember it. But there is one focal point they all share, a girl who became the star of the traumatic mental film reel of their youth. Even though she is a shared feature of all their memories, they all remember her differently. One remembers her hair pulled back in long braids, another swears she wore her dark hair long and loose, framing her face. They can’t agree on the details, but her place in their memory is certain:

It’s her. Nothing else matters, not the style of her hair, the color of her skin or her eyes. Everything is relative except for the sound of her voice, because in dreams, according to Fuenzalida, voices are like fingerprints. González’s voice seeps into us from Fuenzalida’s dreams, invading our own visions, our own versions of González, settling in and keeping us company night after night.

Fernández paints this mysterious central figure, Estrella, with a dash of this dream, a pinch of that memory, from then, from later, from after. Subtle and not-so-subtle repetition and modulation give shape to key scenes and relationships. Strong visual recollections take central places for the members of this group, and these striking elements also mingle and stack. The spare hands of an amputee parent merge alarmingly with the projectiles of their Space Invaders video game. An unmatchable high score left as a challenge by a vanished older brother. A mysterious man with dark glasses and a red Chevy drifts through the background like smoke. The story is built of images, and the images are painted in words. “Maldonado dreams about letters. They’re old letters in the handwriting of ten-year-old girls. […] Maldonado’s dreams are of reading each of these letters. Dreams are built of words, assembled from letters and sentences.” Our understanding of a troubled past is built on shaky evidence, a binder of news clippings, mental inconsistencies, and remembered childhood correspondence.

Natasha Wimmer’s skilled touch is made evident in this translation through her attention to register and tone. Among the various memories, dreams, and attempted explanations, Fernández intersperses a series of short letters from one of the classmates to another, and here, Wimmer’s attention to detail is on display. She informed me that for her, the difficulty lay in finding “the right mix of lyricism and child-like candor.” And indeed, she has, as the letters are charming without being infantile. Devices of this sort risk overwhelming a book, especially one of this length, but in Space Invaders, these epistolary memory-artifacts are occasional anchors to a time of innocence that faded under the weight of the realizations the characters later faced.

The things I have to tell you are other things. More important things, secret things. But this paper is tiny and my writing is so big and fat. My dad says I have to write smaller and stay on the lines but the lines are so thin they’re hard to see. If I listened to my dad I could write more but since I can’t write small and stay on the tiny little lines I have to write less. I should try to obey my dad.

Beyond the letters, it gets increasingly difficult to tell the speakers apart, to tell which of them is relating events, to be certain of whether they are remembering or dreaming. Carefully-crafted repetitions help to tie some things together, just as they help to further blur chronological lines. This is the composition of a generation’s collective memory during times of shared trauma, and it is taking place at a formative age. As many of us have seen recently, when times are tough, memory and dream tend to overlap more than usual. Dreams color memories, and collective memories tug and pull in all directions at once.

Our ten-year-old sons and daughters must be experiencing something similar right now, in these shared days of pandemic-inspired anxiety and uncertainty. While we’re all stuck indoors, many of us are having trouble sleeping, or perhaps having trouble not sleeping. In such a situation, dreams can take on new forms as, for lack of routine and typical stimuli, they are invaded by older memories, by television and books, by the news. What memories are our youngest generation forming of these peculiar days? What will they remember of the great 2020 pandemic? A house full of anxiety? Boredom? The disappearance of a loved one that they were not able to be present for? When we come to the other side of this, they will all share in the memory of this time, of what it was like to be ten in the spring of 2020. They will each remember it differently, they will have retained different details, but together, they will possess a shared experience, because they all went through it simultaneously.

This is not to say that COVID-19 can be compared to an authoritarian military dictatorship and a complete breakdown of democracy, nor that this pandemic will go on for seventeen years. I only suggest that there is a similarity between the two along the lines of the formation of collective memory during trauma. And in a way, during all the anxiety and fear that we are facing throughout such an unexpected and unimagined situation, there is something vaguely comforting in knowing that everyone else is dealing with some version of the same thing, to a lesser or greater degree. This was the case for Maldonado, Zúñiga, and their friends, and it comes across in the prose of Space Invaders. As Natasha Wimmer put it, “There’s something about the third person plural that is just perfect for this child’s-eye perspective–maybe because as children we’re more likely to feel ourselves part of a collective.”

While it is unusual for a novel of this length to win a major award, clocking in as it does at under eighty pages, even at this length, Fernández’s short book is a fully formed reading experience. There is more than enough enjoyment, introspection, and style here to validate picking it a copy. This is a one- or two-sitting read, and as such, there’s no reason why you shouldn’t dive in and experience this insightful meditation on memory, dreaming, and trauma. As an added bonus, it could provide your pandemic-addled dreams with a bit of spice in the form of green-glowing projectile hands.

Leave a Reply