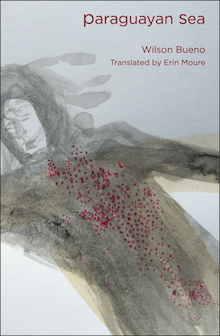

“Paraguayan Sea” by Wilson Bueno [Why This Book Should Win]

Paraguayan Sea is an epic poem in story form about a woman from Paraguay, living in a beach town in Brazil, reflecting on her experiences with two lovers, an old man and a younger one, and using those experiences as a way to delve into the physical, sensual, and spiritual elements of existence. The book is originally written in Portunhol (a mixture of Spanish and Portuguese spoken along the border of where Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay touch) and Guarani, a native language of Paraguay. The English translation maintains much of the Guarani, with a generous glossary in the back, and is inventively interspersed with “Frenglish,” a combination of Québécois French and English. Erin Moure, in her translator note, wrote that she kept Guarani a part of this translation because she, “decided to trust Bueno’s own admonition that Guarani is essential to the text, for Guarani bursts out of his text at every seam, even the most infinitesimal, and its epistemologies and relations are crucial.” In so doing, Moure created a text that is accessible to an English readership, but brings us to Guarani instead of having it diminished and rendered invisible. In this translation, it asserts its own necessity and though we may lose the way it interacts with Spanish and Portuguese, in geographically relevant rhythm, the resonances that emerge from the act of creating another hybrid language offer their own linguistic charms.

He stuck his bouche béante on me as if to suck me totalmente into his hot insides. Yes, aortan blood pulsed in every pore of the oldster. Even though I, once certain caprices were satisfied, for magasins et jewels, cadeaux and grabbags, I’d spit back all that his avid tongue had proferred me in saliva with an undecipherable goût of semen. He tripudiated and wasn’t yet that rascal who’s always skewered, who dies and doesn’t die and about whom, for the nth time je déclare formellement et atteste: it weren’t moi qui killéd the oldie.

It’s a section that lives its own life, satisfying as a whole, read for the voice and imagery and trickery. It’s possible, indeed, that the narrator did kill the old man. It’s possible we never really do find out, but it doesn’t even matter. It’s a voice that allows itself to be slippery and quick, precise yet playful. The other beautiful mystery of such an exacting book is that we don’t really know who the narrator is. A cis she? A gay he, sometimes a she? Everything is fluid here, from the language choices, to the imagery, the characters themselves and the facts or non-facts or sometimes-facts of their lives. It’s a commanding book in that every line and sound and space feels intentional and thoughtfully composed, with an imperceptible formula but an experienced musicality.

After my first few reads of this translation, I wanted to know why some words were translated to Frenglish and why others remained in Guarani. I turned to the passage “one dusk après une autre,” to try and find some answers. The word nandu is repeated many times in this section, so I looked it up, and it’s the name of a flightless bird, similar to an ostrich, common in South America. The exact English translation would be the word “Rhea,” but I could see how the word nandu, instead, allowed for a play on words like: “ostrich-necked, ñanduguasú: fileté in the sand: ñandu: ñanduti: web: the crochet contorting from one stitch to the next: corolla: ramification of hair and ligne: slow announcing the fleur of flower most florid: most michĩ: ñandutimichĩ: almost invisible: miraculum: simulacrum: ñandu: mirroir of God: ñandu: . . .”

The”n” and “m” and “u” sounds dance together in the same word, or across words, then split apart. The language is immediate, entangled, reflective of the moment(s) it describes. I see why we need nandu, what it’s able to do for us. I see a translator making incredibly careful decisions, committing to the pitch of the music it’s espousing. I see a translator having a lot of fun, discovering pattern and rhythm.

assise: fossils of the same species

Je m’assois: I sit . . .

me voir: I seeThese words, strung together, drum up a choral refrain of sorts that suggests waiting, watching, time, discovery. This much I gathered already from all the other context clues (for lack of a better word) and that’s when I more fully affirmed to myself that this experience was not about decoding or revealing what exactly these words meant but more about their collective invocations, about what they’re saying about language as a greater practice, how the various imaginative lives of languages live within and around each other, the way the narrator’s moments of longing and alienation live in a connective tissue of expression. (I say this, of course, after only a few preliminary reads of the book–aware that there is so much complex and intricate etymology at play here, that I can only begin to scratch the surface of at this stage.)

To even begin to detect how these choices were made I had to think less in terms of a formula and instead just let myself experience the sentences, the sounds, the connotations and echoes of known words and imagery, and trust that the way I was experiencing them, literally in my mouth, as I read them out loud, was part of the experience of the text itself. What if there was a better word for the word you want to use, and it doesn’t exist in any one language yet, but you know it when you hear it, or, better yet, you make it a fusion of all the things you want it to be? That is just some of what it feels like to read this beautiful, ambitious, and transfixing book. For Erin Moure to make languages out of languages is a true gift to the forever-open possibility of what transformative literature can do.

I was just reading Paraguayan Sea and I have to say it is wonderful book, I recommended it to everybody who want to find really exciting story.

How do you submit a book for the next prize?

I find nothing about that on the website. Somehow, last year I had no problem.