The All or Nothing of Book Conversation

In theory, this is a post about Norwegian female writers in translation. I know it’s going to end up in a very different space, though, so let’s kick this off with some legit stats that can be shared, commented on, and used to further the discussion about women in translation.

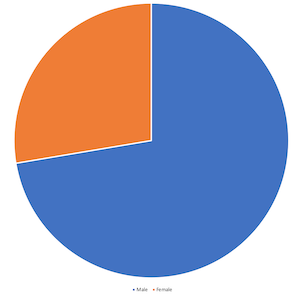

Back in the first post of July—Norwegian Literature Month at Three Percent, because nothing reminds me more of Norway than a 110 degree heat index—I shared a bunch of statistics on Norwegian literature in English from 2008 through 2018. Including this:

This is the breakdown of Norwegian books by men (123 titles or 73%) published in English translation compared to those written by women (47 titles or 27%). That’s a huge discrepancy! Almost three titles by Norwegian men for every single title by a Norwegian woman? Not a great look.

And because I have the data in front of me, I can list all 21—only twenty-one!—Norwegian women who, since 2008, have had work translated into English for the first time ever:

Selma Lonning Aaro

May-Brit Akerholt

Merete Andersen

Brit Bildoen

Hanne Bramness

Gro Dahle

Janne Drangsholt

Karin Fossum

Kari Hesthamar

Vigdis Hjorth

Anne Holt

Merethe Lindstrom

Maja Lunde

Hanne Orstavik

Gunnhild Oyehaug

Edy Poppy

Agnes Ravatn

Ingelin Rossland

Kjersti Skomsvold

Amalie Skram

Linn Ullmann

Compared to a number of other countries, that’s not bad, but aside from the mystery writers—Karin Fossum and Anne Holt in particular—and the one(?) Big Five author (Gunnhild Oyehaug), I’m curious to see how many of these other authors are easy to find out about online.

Let’s back up for a second first.

*

Shortly after putting together a really ambitious plan for Norwegian Month—and a to-do list that’s longer than a Texas mile—I took a kind of selfish “work” vacation. I went to an AirBNB alone (a place with no TV and no Internet) to work on a book idea I had (er, have, I suppose) about, well, baseball and framing and stuff. The vision I have makes no sense when I explain it, no matter how valiantly I try, but, in essence I want to write about non-quantifiable value at a time when everything is being quantified and analyzed.

The biggest problem I’m having—aside from a near-constant state of self-deprecation, especially when I think that these posts can serve as some sort of “proof of concept” behind my whole insane book idea—is that writing about value mostly means writing about failure. And when I’m writing about failure—in a book that’s at least partially autobiographical—I’m really just pondering my own failures. And how my life/career/ideas/editorial selections stack up against others. Definitely not well!

Anyway, putting aside that moment of self-doubt (fuck self-doubt! fuck aspiration! fuck ego! and fuuuucccckkkk Twitter!), my other big plan for my time away was to read a couple books by Norwegian women—the two that are referenced below—and prep some posts for Three Percent.

That didn’t happen.

Instead, I discovered Shirley Jackson, aka, one of my five most favorite authors ever of all time.

This started by downloading Hangsaman for my Kindle before taking off to the AirBNB. (And please, come at me if you want. If you work at an indie bookstore between Rochester and Great Barrington, MA and had a copy of Hangsaman in stock, please send a picture. It wasn’t available in the central library here, nor in the U of R one, and, to be honest, there is something rewarding about being able to read in the dark, on a roof, well into the wee hours of the morning.) Hangsaman came up in a marketing meeting about Sara Mesa’s Four by Four, as a suggestion from one of our summer interns as a possible comparison, and as a voice that might help with editing this strange, captivating book.

(Side note: Four by Four is AMAZING. It’s the sort of book that gets stuck in your mind, forcing you to puzzle it all out. And dwell on it. The editing process has been incredibly illuminating for this title. We’re taking the translation to a new level. Just wait, y’all. Just wait.)

Everyone who went to high school already knows of Shirley Jackson. She’s the author of “The Lottery,” which, because bold claims are the thing in 2019, I’m going to state, emphatically, with no qualifications or any hand-wringing, that this is the Greatest American Short Story Ever. We all know it. It caused a bit of controversy. It’s layered. It’s immaculately well-crafted. It’s singular in its voice. And it’s not by Hemingway. (Big plus.)

Everyone who watches Netflix knows about The Haunting of Hill House, which is pretty much not at all related to the Jackson novel of the same name—but who cares? Lots of people watched this. “Inspired by” is the new “adapted from.”

And some people know We Have Always Lived in This Castle, which I first heard about and read in 2008 when Bragi Ólafsson recommended it during his reading tour here in the States. When the aforementioned intern recommended Jackson as a possible comparison point for Sara Mesa’s novel, this was the book I thought of. A novel with a weird interplay between voice and perspective, plot and narrative framing.

I didn’t want to reread that, though, which then led to my finding out that Jackson had written four novels I’d never heard of: The Road through the Wall, Hangsaman, The Bird’s Nest, and The Sundial.

I have no doubts that some readers of this website have read some/most/all of these books, but for whatever reason—because of “The Lottery”?, because she’s a she?, because her books are supposedly “genre”?—Jackson flew under my radar.

Looking at her earlier books, Hangsaman jumped out. A book about a school (like Four by Four) that’s both sinister and a parody (again, Four by Four), and a lesser known book from a famous author (I am a total mark for being “that guy who read the book by XXXX that no one else ever reads”), sounded ideal to me.

In fits and starts, as I worked on my book (aka came to terms with several of my limitations as a writer and thinker), I read Hangsaman. And when I finished, I had two thoughts: What the fuck did I just read? Who else has written about the connections between this book and Twin Peaks?

*

The first book I planned on reading on my little write-a-cation (I’ll let myself out) was Anatomy. Monotony. because the description sounded so very horny. (FYI: Dalkey’s website is still fucked. Can someone let me know what’s going on? Anyone?)

What is fidelity? In Anatomy. Monotony., Edy Poppy examines this question with an intimacy and ruthlessness worthy of Marguerite Duras. Vår, a young woman from a small Norwegian town, and Lou, a Frenchman from Nîmes, maintain an open marriage. But their polyamorous experiment is freighted with jealousies. Their life in London is broken into by one fascinating stranger after another, until eventually they decide to move away, back to Vår’s rural hometown―a decision that will change the nature of their relationship forever. Anatomy. Monotony. is a novel about sex, love, and the creation of literature in no uncertain terms.

Admittedly, I’m not digging too deeply into my Google results, but at first glance, there seems to be almost no conversation whatsoever of this book. Michael Orthofer gave it a B- “too personal, too forced,” and TLS gave it a paragraph. LitHub ran a legit interview (definitely worth checking out), but RTE Ireland’s article wins, due to this opening paragraph:

I have lived with the novel Anatomy. Monotony. for the entire 19 years of my real-life story with its author, Edy Poppy. I’ve known its players, the inside story – from her first notes in the galleries of Tate in London. Now I have a chance to read it. Dare I?

Oh, shit!

*

The first result I got for “what does Hangsaman by Shirley jackson mean?” was a GoodReads page that was basically a cold, objective evaluation: With a grand total of 9 ratings, the book had received a 3.22 rating.

NOT A SIDE NOTE: What is a small sample size for book review ratings? In baseball, 600 plate appearances is pretty valid. No trends stabilize before 100 plate appearances. But off of 9 GoodReads ratings this book is mediocre.

This book is definitely not a 3.22 out of 5.00. That’s like giving a C to a student because you’re too dumb to notice they know more than you. But who’s going to go on there and try and change that score? What are we doing, rating books in this way?

*

Vigdis Hjorth is a big name in Norwegian literature. Her novel Will and Testament (forthcoming from Verso) sold like, if I can remember the number from the press release I threw away, like 140,000 units.

Open Letter has sold more than 120,000 net units over our history. That’s not a failure. I don’t think? It’s not. No way. Success isn’t only sales figures. Right?

Four siblings. Two summer houses. One terrible secret.

When a dispute over her parents’ will grows bitter, Bergljot is drawn back into the orbit of the family she fled twenty years before. Her mother and father have decided to leave two island summer houses to her sisters, disinheriting the two eldest siblings from the most meaningful part of the estate. To outsiders, it is a quarrel about property and favouritism. But Bergljot, who has borne a horrible secret since childhood, understands the gesture as something very different—a final attempt to suppress the truth and a cruel insult to the grievously injured.

Will and Testament is a lyrical meditation on trauma and memory, as well as a furious account of a woman’s struggle to survive and be believed. Vigdis Hjorth’s novel became a controversial literary sensation in Norway and has been translated into twenty languages.

I did read a bit of this book. My hot takeaway: It’s worth checking out, but the most interesting part of the first 60 pages is about the narrator having an affair with a married man. The most boring parts are all the whining about the summer houses and the inheritance. It’s very repetitive. But I assume it becomes more and more interesting as it goes along. In Verso I trust. They are not failures. Every editorial decision they make is lauded.

That said, Will and Testament is no The Sundial by Shirley Jackson, which I immediately downloaded after finishing Hangsaman (although, in all fairness, I did go to the local independent bookstore, The Bookloft, and bought the only Jackson book they had in stock, a Netflix tie-in version of The Haunting of Hill House), and ended up devouring over the course of a single day.

*

All clickbait headlines are awful, but this one really bugs me: “Shirley Jackson’s Hangsaman: What Does it Mean?“

I’ve spent the week so far reading mid-century-style: pocket paperbacks and folded pages, making notes in the margins with ballpoint pens. When I finish Shirley Jackson’s 1951 novel Hangsaman today, though, I immediately head to the 21st century—I take out my phone and start Googling furiously.

What else would you do? Everything you can imagine exists online somewhere, so, obviously, someone must have tried to articulate this weird novel. Go on, Dan Kois, editor of Slate:

“Natalie is lonely at school. And because of who she is, and because of what kind of novel this is, her loneliness is terrifying. The dangerous power of awareness, quotidian social brutality, loneliness, and existential fear propel Hangsaman toward the edge of becoming a psychological thriller, rather like one of Patricia Highsmith’s, only less physically violent, funnier, more lyrical, imaginative, and interior.”

At the very least I’m reassured that I didn’t miss some enormous plot point. Instead, I’m left with the thoroughly enjoyable activity of chewing over the book I’ve just read: thinking back on Natalie’s voices, her diaries, her puffed-up father and desperate mother, the man at the party, the one-armed diner and the best friend, only some of whom, it’s clear, actually exist.

Just to clarify, Dan quotes Francine Prose’s intro, and then reassures himself that his (unarticulated) reading of the book wasn’t 100% off-base.

It would take many more paragraphs to address even half of the interesting things you can find in this book. Questions or observations like:

1.) Natalie was sexually assaulted, right?

2.) What an amazing parody of a domineering father . . .

3.) . . . AND of a man who thinks he’s a writer.

4.) Those letters home from college.

5.) The history of that college (Bennington?) is so wonderful in its specificity.

6.) And that ending? Let’s assume Tony isn’t real. Natalie still has very uncanny experiences with several adults in the last third of the book.

7.) Including the very unnerving car ride back to town, which seems to take place at a very different point in time.

9.) And don’t forget about the 0ne-armed man!

But is any of this addressed in the only contemporary review of this book? Nope! The rest of his review is this:

My hunch is that the establishment of the trade paperback as an exciting format for lit-fiction—cemented by the amazing Vintage Contemporaries line, launched in 1984 and a fabulous success almost instantly thanks to Jay McInerney’s Bright Lights, Big City—meant that suddenly every author wanted a large-format paperback edition for herself. They also cost more: more money for publishers, higher royalties to authors. So where once most trade paperbacks were, as this blog post points out, academic books, that format now became a way to differentiate high-toned fiction from its pulpier, poppier, mass-market brethren. The bet was that readers would pay for quality. For a while, they did.

Now, of course, the only thing I’m willing to pay for is speed. I spent $8.89 to download a book in seconds, even though it’s just data, words on a screen, more ephemeral even than the shabby mass-market tucked into the cupholder of my beach chair. Fifty years from now Hangsaman will be over 100 years old, and this little object that once sold for 50 cents may well still survive—in my daughter’s house, or in a thrift shop somewhere, or on the shelves of some other mass-market fetishist like me, carefully tending the last remaining treasures in his collection. That $9 Kindle version will be long evaporated into the ether, just another obsolete file format, more orphaned data lost in the dark where no one will ever find it.

Wait, what?

*

Every Shirley Jackson book I’ve read has a moment when the main character gets lost in the woods and has some sort of vision that’s maybe real, maybe in their (broken) mind, possibly supernatural. Someone must be talking about this. Somewhere.

*

Where does discussion of the not-mega-popular books take place nowadays?

This is something I want to include in my aforementioned book in progress—or on a podcast, or something—but the democratization of book culture via the Internet has only really reinforced the gap between immense success and being completely ignored. A book is only going to be talked about in detail if everyone is talking about it. It’s very rare to see someone going out on a limb and talking up a book that others haven’t already anointed. Or that isn’t positioned to be “the next big thing.”

Which will always strike me as weird, since I grew up at a time when everyone was desperately trying to set themselves apart through their choices of which bands, authors, movies, etc. Never admit to liking a book that normals really like.

I don’t feel like that’s the vibe anymore, although maybe I’m just wrong. Twitter is probably not the best way of assessing culture at large.

*

The only other thing I could find online about Hangsaman was on Reddit. Initially, this made me feel hopeful. It would make sense for conversations about more obscure books to happen here. But then, this:

This is the fourth book I’ve read by Jackson. While all of them seem to leave open-ended plot lines and questions, none so far has been like this one. Elizabeth and Arthur Langdon are made major plot points when Natalie first arrives at college. But there never seems to be a resolution. Were they simply included to give Natalie a glimpse of what her life might be like should she get married young? Elizabeth is obviously incredibly unhappy, while Arthur seems much more interested in his students than his wife. There is also the brief friendship with the two rich girls she meets at the Langdon’s. After hosting a party with Arthur and Elizabeth, where Natalie has to walk Elizabeth home due to her being very drunk, I don’t recall those two girls ever being mentioned again. Lastly, there’s the whole issue of Tony. First, I don’t recall any real interaction between Natalie and Tony other than a brief conversation between them on the Landon’s front step. Suddenly, when Natalie returns from a trip home, they interact as if they’ve been friends for a very long time. Natalie goes to Tony’s room to talk and gets in her bed as if it’s been something they’ve been doing forever. Then there’s the ending of the book (again, massive spoilers). Was Tony planning to kill Natalie on the path in the trees? Was there some sort of planned initiation ritual waiting for her due to her not participating when she first arrived at college. Was Tony even real at all? I found myself asking this question several times. Natalie seemed to have a very over-active imagination and I found myself wondering whether Tony was just a product of that. Any thoughts?

I have some! But what do the other Redditers have to say? Well, there’s only one response, and it’s kind of boring.

Hangsaman is in many ways Jackson’s most experimental and vague novel (only The Bird’s Nest comes close). In later works, Jackson posits protagonists like Eleanor and Merricat as unreliable narrators, but in books whose genres – haunted house and gothic – invite that conceit almost as said.

Presenting however as more ‘mainstream literature’, the narrator of Hangsaman is unreliable, though the book is not written in the first person. It is a novel written with awareness that it is a novel, but playing with the form. Jackson was also a self-proclaimed witch, and Hangsaman may be the closest she came to casting a spell with words.

All of your questions are valid (especially regarding Tony), but I would recommend later reading the book again, keeping them in mind.

“Presenting however as more ‘mainstream literature'” feels like a hipster T-shirt.

*

So, how does this relate to books by Norwegian women? It doesn’t, necessarily. Although if a novel by one of the most famous writers of the twentieth century doesn’t generate even a cursory post about the book’s actual plot or style or anything, what are the odds that a book in translation would?

This is going back to the old point that I’ve written about (and podcasted about) a million times, but the most pressing issue for the field of international literature isn’t increasing the infamous 3% number, it’s cultivating conversations around the books that are published. Of the 600+ translations published last year, there were probably a dozen that received a respectable amount of attention from reviewers, literary websites, booksellers, Twitter, and the like, with the overwhelming majority of international titles (and, to be honest, most books in general), just fading away.

None of this is new, or insightful. But if you start to unpack why certain books receive 90% of the conversation, and others get absolutely nothing . . . That’s interesting. Even a bit disconcerting if you accept that it’s not the best or most worthy titles that get the attention, that there are other forces at work, shaping our culture. (Shadowy forces and luck. It’s always all about luck.)

So it’s not surprising that it’s hard to find people talking about Will and Testament (hopefully that will change when the book is officially released) and Anatomy. Monotony. I’m not sure there’s anything to be done, but I’m becoming more and more despondent about a culture that seems to only value the mega-hit. Twitter broke me this week when, after not checking it for days and days, I opened up the app and saw every silly tweet as someone’s attempt to go viral. Just keep chucking out those puns and witty observations and one day you’ll make it! Like trying to understand YouTubers, this really bums me out. We don’t see value in the object itself, but rather in the number of references and likes that object has received. And since most people, especially nowadays, want to be part of the in crowd, once something starts to be popular, we all rush to like and retweet it, to make sure that we can demonstrate that we know what’s good.

*

Hangsaman is a fantastic book. And The Haunting of Hill House is exquisitely crafted. But, in the end, my favorite Shirley Jackson novel is The Sundial. It’s one of the funniest books I’ve ever read, a sort of comedy of manners set against a somewhat sinister backdrop. The Victor LaValle foreword (posted on Slate as a “book review,” which is odd) does a great job articulating what makes her book so damn good:

The Hallorans, and their extended hangers-on, become a kind of cult when one of them, Aunt Fanny, receives prophetic messages from her long departed, much revered father. He has appeared to his only daughter to warn that the world is soon to end. All those in the Halloran home must prepare for the coming doom. Shut the doors and windows, close themselves off from the cursed world. Prepare to become the last of the human race. In quick time the family members are drawn into paranoia and conspiracy. They come to believe the prophecy. They have been chosen to inherit the earth. Jackson proceeds to illustrate, in rich detail, just how sad such a fate would be. The whole world ends, and this is all that’s left? Jackson spares no one her precise, perceptive eye. Sadder still is how much I recognize myself, from my worst moments, in one character or another. What saves me from despair is Jackson’s wit, her deadpan demolition of human foibles. For me, that kind of reading experience is essential, and when I discovered Shirley Jackson, it was as if she’d understood what I wanted, what I needed, and set it all down on the page long before I was even born. That recognition is profound, life changing, whether it comes in a darkened movie theater or between the covers of a novel.

Personally, I love the way Aunt Fanny keeps trying to get in bed with one of the hangers-on by pounding on his door and insisting that she’s “only 48” and therefore, still desirable. That and how the granddaughter keeps questioning whether or not the post-apocalyptic world, in which everyone outside of the house has simply vanished, is actually a good thing, since they’ll all still be stuck with one another . . . Oh, and the set-piece where the Halloran Cult meets the True Believers, who share their own vision of the coming end of the world—a vision that the Hallorans find absolutely ridiculous. (I don’t want to give away any more of that scene though . . . Those few pages alone are worth the price of admission.)

Leave a Reply