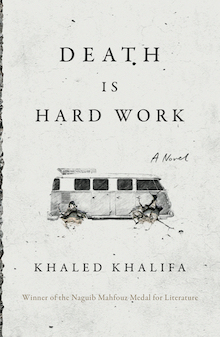

“Death Is Hard Work” by Khaled Khalifa [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards.

Tony Messenger is an Australian writer, critic and interviewer who has had works published in many places including Overland Literary Journal, Southerly, Mascara Literary Review, VerityLa and Burning House Press. He blogs about translated fiction and interviews Australian poets at Messenger’s Booker and can be found on Twitter @Messy_tony

Death Is Hard Work by Khaled Khalifa, translated from the Arabic by Leri Price (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux)

Khaled Khalifa’s fifth novel, Death Is Hard Work is the first Syrian novel to make the Best Translated Book Award longlists although another Syrian book, Adrenalin by Ghayath Almadhoun (translated by Catherine Cobham) made the poetry longlist in 2018.

Khaled Khalifa’s four previous novels include In Praise of Hatred, which was shortlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction, and No Knives in the Kitchens of this City, which won the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature in 2013. He continues to live in Damascus and writes in cafes despite the obvious dangers. Despite offers for overseas university postings he remains in Damascus, a city he has refused to abandon despite the danger posed by the ongoing civil war.

Death Is Hard Work has a simple narrative: Abdel Latif al-Salim dies on the opening page. His dying wish is “to be buried in the cemetery of Anabiya…beside his sister Layla (also known as Nevine).” His son, Bobol, gathers his siblings, Hussien and Fatima, to undertake the long journey, “hundreds of miles away,” to the ancestral village.

A literal and figurative journey back to simpler, safer times.

Although simple in plot, Khaled Khalifa uses the journey to explore many themes. Syria, like the corpse, is in decay, the matter of fact approach to death in a decimated country, the reconciliation of familial bonds as they are forced to share a minibus together, and a whole lot more.

From the opening pages, there is a blend of horror, tinged with bureaucracy, Bobol cannot remove his father’s corpse without the Director’s signature, but the morgue is quickly filling:

Death is a solitary experience, of course, but nevertheless it lays heavy obligations on the living. There’s a big difference between an old man who dies in his village, surrounded by family and close to the cemetery, and one who dies hundreds of kilometers away from them all. The living have a harder task ahead of them than the dead; no one wants to see their loved ones rot.

Once settling the father’s corpse in Hussien’s minibus, and plotting their way out of Damascus and the roadblocks, and oncoming vehicles filled with corpses, the trio work their way out on the open roads towards the ancestral village. Soon they have to leave the highway as there’s a sniper hiding. Beside the road lie the bodies of “a man, a woman, a young man and a girl” victims of the sniper. These repetitive experiences of death reinforce the horrors besetting their nation: “The exceptional had become habitual, and tragedies were simply mundane—perhaps that was the worst part of this war.”

Endless checkpoints and delays hinder their journey, and slowly the corpse begins to decay: “Driving along in the dark, the siblings hadn’t noticed the changes that had overtaken the body.”

This a parallel to the decay of their country, Syria slowly rotting and becoming unrecognizable, storage in local morgues is interrupted as the bodies of soldiers killed in battle take precedence, you can only stall the inevitable decay for so long. And, finally, what once was living and vibrant has now rotted to become unrecognizable. In an interview, at Electric Literature, Khaled Khalifa speaks of this metaphor: “Syria became a corpse not only during the war, but it was also becoming that corpse slowly and day by day during fifty years of dictatorship.”

Bobol’s memories give the backdrop to the escalation of the conflict: “Suspicions alone were enough to lead to corpses lining the streets. Suspicions alone were enough to cause someone to disappear without a trace.”

The history of the escalation blended with the current reality and the hopes and dreams being extinguished: “What was the point of clinging to memories as life went by? They were only good for digging up more pain.”

Having a journey and taking place in a minibus, a restricted environment, the novel allows for the familial bonds to play out between the two brothers and sister: “Hussein didn’t care, Bolbol actively opposed it, and Fatima was too busy trying to play the role of the noble sister reuniting her family after the death of a parent.”

However even under strained conditions there are still hidden family secrets: “He had wanted to tell Hussein all the things he had smothered within himself for years, but there hadn’t been a point during their journey when it wasn’t either inappropriate or simply too dangerous to talk.”

And finally, this is a novel that is also a journey into the unknown: “It was a mass exodus, hundreds of thousands of people heading from the north and the east toward the unknown.”

A novel that also contains tinges of romance, failed first loves, and even absurdist humor (for example, the corpse requires identity papers), this is a fine example of how literature can parallel and mimic a brutal and inhumane situation. Khaled Khalifa, and the work of translator Leri Price, has brought to the Western sphere a multi-layered book that forces the reader to confront the horrors of the Syrian crisis. The first novel from Syria to make the Best Translated Book Award longlist and a worthy inclusion.

Leave a Reply