“The Boy” by Marcus Malte [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards.

Lara Vergnaud is a literary translator from the French. She was the recipient of the 2019 French Voices Grand Prize and a finalist for the 2019 BTBA. Her work has appeared in The Paris Review Daily, Words Without Borders, Asymptote, and elsewhere.

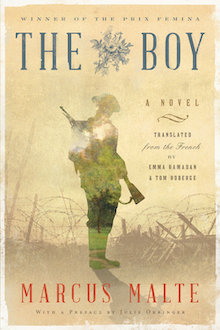

The Boy by Marcus Malte, translated from the French by Emma Ramadan and Tom Roberge (Restless Books)

First sentences aren’t everything. Except they kind of are, aren’t they? This is the opener of The Boy:

Even the invisible and the immaterial have a name, but he does not.

“He” is the mute, feral boy who drives Marcus Malte’s sprawling novel, which spans thirty years, much of France, one world war, and the earliest harbingers of the second one. The Boy won’t say a single word.

Occasionally, I will read a novel without looking at the front inside flap or back cover, going in blind. I wish I’d done that with The Boy. The book starts like a grim, dystopian tale: the Boy lives with his mother in the wilderness that still remains in turn-of-the-century France. She dies, leaving him to fend for himself able to hunt, fish, climb, hide, etc. but with no conception of his fellow man. What follows is the Boy’s journey toward (into) society, slowly leaving behind woods and rivers for farms, running water, prejudice, and worse.

This part is long—so long that a reader might justifiably be concerned about a Castaway-esque monotony: boy hunts rabbit, boy skins rabbit, boy eats rabbit. But no fear, Malte is an expert craftsman, his plot quietly accelerating despite the painstaking detail accorded the Boy’s physical environment. The author also knows to give us breaks, offering piercing observations about the human condition:

He has not yet asked himself whether [mankind] is a good thing in the end. Whether it’s a desirable thing. He has not yet told himself that it’s meaningless.

And then cuts to this, which I can confidently describe as my favorite literary passage about frogs:

He eats the frogs dusted with rosemary flowers.

He eats the frogs sprinkled with savory.

He eats the frogs rubbed with sage leaves.

He saves the last bone of the last skeleton and places it in his matchbox as a kind of talisman.

Had I not read the synopsis, or glimpsed the cover of the book, I wouldn’t have known The Boy is a war story. I wouldn’t have known because after starting as a pseudo-post-apocalypse novel, unexpectedly, after pages of frog-hunting and tree-climbing and apple-picking, The Boy gets steamy, pages and pages of sex, until, finally, we get it: this is a book about war. The author tells us as much on page 307:

This is the story of those who will die.

The first two sections of the book—the journey from wilderness to society, and a sexual awakening—could be novels apart. But the war part is what gets you, is what got me. The Boy is punctuated with historical asides, frequently as stark lists of dates and names—just often enough for effect. In 1912, “Eva Braun comes into the world.” The same year,

Jean Baptise Blumet, twenty-six years old, dishwasher, perish[es] off the coast of Newfoundland, at 41° 46’ N latitude and 50° 14’ W longitude, in the shipwreck of the unsinkable transatlantic liner baptized Titanic.

Malte interweaves this historical framework with visceral portraits of the battlefield. Death, dismemberment, disease, all of it; but also, monotony, resignation, boredom, terror, the savagery that forms, or rather rises from within. All with a protagonist who never speaks.

There’s little doubt Malte gave his translators a difficult challenge. To their credit, you can’t tell there were two of them—Emma Ramadan and Tom Roberge, who, incidentally, are married. Or not incidentally. Having co-translated with both friends and acquaintances, I can easily believe that the intimacy of marriage fosters an especially seamless translation, though perhaps the arguments over semantic choices are somewhat more intense. I like to picture chilly debates over morning coffee: innards or viscera, dear?

The Boy is rife with translation pitfalls. French has the perfect noncommittal pronoun—on, which can be understood as either “they” or “we.” If you opt for they, you risk removing the universality of a text; we, and you might eliminate necessary distance. In this novel, imagine a world-weary narrator, he’s told this story before, or some version of it; he uses on constantly. Ramadan and Roberge smartly chose to translate it as “we.” As a result, as with the French, the reader is involved, attentive.

Now the boy has his bearings, he recognizes his guideposts, he is back on his path. [. . .] Towards what destination? To what end? Deep down, we don’t really care to know, but we catch ourselves hoping that they’ll reach it.

Verb tenses in the book are tricky too, switching from present to past in a way that shouldn’t function, grammatically speaking, yet does. These passages can’t have been easy to translate, but again, Ramadan and Roberge look to have navigated them with ease. The same for transitions between second person and third.

I’m always wary when cautioned to patience before even starting a book, as Julie Orringer does in her preface to The Boy. But to be fair, patience is required. The novel isn’t perfect. To start, it’s thirty or forty pages too long. And at times Malte can be too clever by a tad. The Boy is teeming with obscure references—music, history, art, literature (and smutty literature! the smuttiest of nineteenth-century French poetry and prose, folks!) But the author is easily forgiven. A French reviewer, Christine Ferniot, wrote that Malte “has both nerve and well-placed ambition.” Well-placed being the important bit, I think. This is hardly the sole novel to tell of a boy returning from war, no longer the same, to a girl, no longer the same. And yet, it’s all in how the tale is told, right?

Leave a Reply