Alumni Gazette

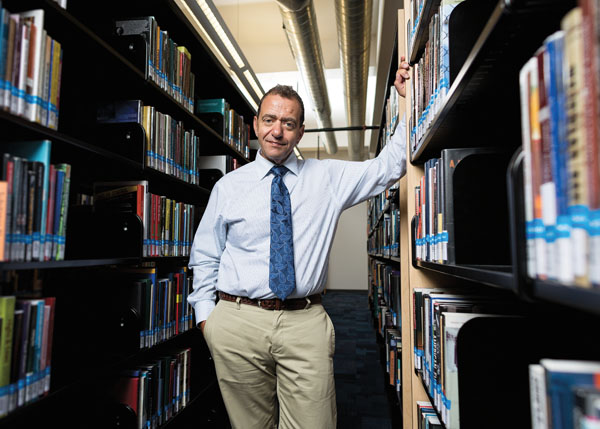

MORE THAN MEETS THE EYE: Certain police procedures may inadvertently encourage eyewitness misidentifications, says Cutler,

a psychologist who has been a leader in state-level efforts to reform eyewitness identification procedures. (Photo: James Kachan/AP Images for Rochester Review)

MORE THAN MEETS THE EYE: Certain police procedures may inadvertently encourage eyewitness misidentifications, says Cutler,

a psychologist who has been a leader in state-level efforts to reform eyewitness identification procedures. (Photo: James Kachan/AP Images for Rochester Review)Studies that gauge the reliability of eyewitness testimony go back more than a century. So, too, does evidence that eyewitness memory is often unreliable.

Yet eyewitness testimony is used routinely in criminal trials, and experts count eyewitness misidentification as a major contributor to wrongful convictions.

According to psychologist Brian Cutler ’82, inaccurate eyewitness testimony is rarely the result of ill intent. “We can often believe, with very high confidence, in the accuracy of our mistaken identifications,” he says. Yet the consequences of those errors are enormous. “Wrongful conviction is a real social problem, and it has been for decades.”

According to statistics gathered by the Innocence Project, a litigation and public policy organization affiliated with Yeshiva University’s Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, eyewitness misidentification has played a role in the conviction of three-quarters of the more than 300 prisoners in the United States who have been exonerated through DNA evidence.

What Is to Be Done?

The development of DNA testing in the early 1990s led to a wave of post-conviction exonerations, and in turn, focused attention on the factors leading to wrongful convictions.

Cutler says a key turning point came in the mid-1990s, when then Attorney General Janet Reno focused her personal attention on the problem of wrongful convictions and the role of eyewitness misidentification.

“A wave of reform began to happen, and since then, a number of states and many police departments have implemented real change,” says Cutler.

Which of those changes would Cutler like to see universal? He offers six priorities:

- Police should present witnesses with photo arrays or live lineups, rather than show-ups. Show-ups present the witness with only one possible suspect.

- Witnesses should have no exposure to the suspect, or to a photo of the suspect, prior to seeing the photo array or lineup.

- Eyewitnesses should receive cautionary instructions that indicate that the suspect may, or may not be, present in the line up or photo array.

- Photo arrays or lineups should include fillers that match the witness’s description of the perpetrator.

- The person who conducts the identification procedure should not know which photo or person is the suspect.

- Police should assess the confidence of the witness immediately after the identification and prior to providing the witness with any information that confirms or contradicts the witness’s selection.

Cutler, who has consulted for the Innocence Project, has studied eyewitness memory for more than two decades. He estimates that he’s provided expert testimony on the potential pitfalls of eyewitness accounts in more than 150 cases in both state and federal courts. The author, most recently, of Convicting the Innocent: Lessons from Psychological Research (American Psychological Association), Cutler is an associate dean and professor at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology, an institution founded just 10 years go that he joined in 2008 to help establish its forensic psychology program.

Your research suggests that well-intentioned witnesses, often certain of what they saw, still are often mistaken. Why is that?

Humans, in general, have good memories. It’s adaptive for us to have good memories. You don’t have much difficulty, for example, recognizing people you know, such as family, friends, or coworkers.

But there are limits to our memories, and the ways that crimes often occur challenge these limits. When somebody is robbed by a perpetrator, it often happens very quickly. It’s by a stranger. There might be a weapon present. So the witness might be under high stress. The conditions don’t facilitate accurate memory.

There are other factors. We know that people are less accurate at recognizing people of other races than people of their own race. The perpetrator might be disguised, might be wearing a hat, which covers some of the cues to recognition. Witnesses are still often accurate. But they’re often mistaken.

Do bystander witnesses tend to have more accurate memories than victims?

There is some research on this. A victim might experience a lot more stress than somebody who’s watching a crime take place. A victim might be right up close, whereas a bystander witness might be 30, 40, or 60 feet away. In that case, we’d look at the impact of distance on people’s ability to perceive.

What role can the personality of the witness play in mistaken identification?

It’s true that some people are just more confident based on their personalities. For example, do you know people who are always confident, whether they’re right or wrong? Do you know people who are never confident, even though they’re often right? So sometimes witnesses are just confident on their own, and confidence is just another psychological variable.

Can police procedures play a role in mistaken identification?

Yes. Police can facilitate accurate recognition, or they can impair accurate recognition, in the way the police go about testing memories for perpetrators through things like show-ups, photo arrays, and lineups.

In cases in which police impair accurate recognition, the witness is being influenced by the police investigator. In these cases, there’s a chain of events that can make less confident witnesses more confident. For example, if a witness makes a tentative identification, and then a police officer says, “yeah, that’s who we think it is,” the witness becomes more confident. And then if the police find more evidence against the person and bring him to trial, that could make the witness more confident, so by the time they get to the stand, they think that everybody knows the guy’s guilty.

In addition, if a witness mistakenly identifies an innocent person as a suspect, the police might then bring that innocent suspect in for interrogation. And the techniques they use for interrogation, which are very successful at getting guilty people to confess, can also lead innocent people to confess. Then if the witness learns that the suspect confessed, that makes the witness even more confident.

In other words, bad evidence often leads to more bad evidence.