“Iron Moon: An Anthology of Chinese Worker Poetry” [Why This Book Should Win]

This Why This Book Should Win entry is from Raluca Albu, BTBA judge, and editor at both BOMB and Guernica.

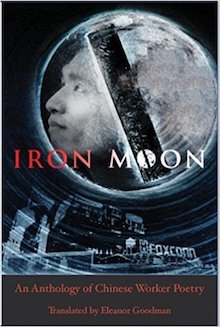

Iron Moon: An Anthology of Chinese Worker Poetry, translated from the Chinese by Eleanor Goodman (China, White Pine Press)

“Iron Moon” is an anthology of Chinese migrant worker poetry that transports the reader from the comfort of the page to the complex machinations of 21st century industry.

This kind of poetry first appeared in China about three decades ago, when Deng Xiaoping’s government advanced China’s industrial complex and motivated a mass migration from the countryside to urban centers. Nearly 300,000 people were involved in this shift, but according to editor Qin Xiaoyu’s introduction, “China leads the world in work place injuries, occupational diseases, and psychological problems . . . problems [causes by these mass migrations include] left behind and homeless children, empty-nesters, an increased divorce rate . . .”

The poets in this collection include men and women who have worked as brick layers, in coal mines, on demolition sites, as stone masons, on road crews at hydroelectric stations, and in plastic factories, to name a few. Others have planted rice, assembled refrigerator parts, and put together enamel wire. Some poets, like Chen Caifeng, only have a middle school education. He wrote the poem “The Women,” about his observations of female factory workers, and “Under Fluorescent Lights” where he personifies mechanization, “The rotary files polished by burrs / follow a series of stiff motions / under the fluorescent lights, frantically / seeking out any possible happiness.” Zheng Xiaoqiong graduated from nursing school and worked at a toy factory, a magnetic tape factory, and as a hole punch operator before she became an editor at a magazine. Her prose poem, “Life,” takes on a philosophical tone, “I don’t know how to protect a silent life / this life of a lost name and gender…” These poems critique, lament, attack, reflect, invite and expose the realities of working class realities in the new century.

The poems in this collection document the longings today’s migrants have for their hometowns, the struggles of alienation that they faced in urban centers, faced with the challenge of living on the lowest rungs of society. It’s truly incredible to read a collection that holds so many of these experiences and shared proclivities — to have a class not just of laborers, but of the dedicated poets amongst them, finding a shared proverbial home across provinces and experiences, in the nebulous possibility of verse. The poets here are not the archetypal literati intellectual (and that’s definitely a compliment). They come from realms of society that we rarely see overlap — and to have access to both in their work opens up a world of detail and sensibility. In that, and other ways, this collection is dualistic in nature. It’s about both the global forces that impinge upon the modern migrant laborer, and about the specificity of the localized roots one longs for.

The themes and symbols one would expect of labor poetry reoccur throughout the collection, especially that of the screw, an image used to ominously foreshadow poet Xu Lizhi’s suicide off the Foxconn Factory roof (where many of our Apple products are made), in his poem “A Screw Plunges to the Ground.” The shared refrains throughout highlight the incessant reiteration of trauma across these experiences. Yet despite the fact that the collection touches on expected and familiar tropes (blatant exploitation, fatal injuries, missing appendages, metal, mothers, secret lovers, darkness, assembly lines, and railroads), these are emotionally authentic portals into worlds and experiences few of us know first hand, despite our complicity in these systems. Do you know what a Banbury Mixer is and what happens when gum, raw petroleum, and white carbon “roast inside its belly?” Chi Moshu’s poem, “The Rubber Factory,” will tell you — and you have to wonder how he composed it, before he ever put a word down on paper, through the chasm-turned-art of his daily observations and sensations.

The collection has its share of surprising and playful work as well, including Xu Lizhi’s “Obituary for a Peanut” which reappropriates the food label on a peanut butter jar, and Chen Nianxi’s clever yet devastating “Yang Sai and Yang Zai,” referring both to a gold ore mine and a co worker who suffers the consequences. Xie Xiangnan’s “Let’s Have More Poets Like Xie Xiangnan,” balances a tone of self sustaining celebration with stirring imagery, “winter seized the autumn’s hair, entering the body of the world from behind” and his “On Sunday, We Gather in the Post Office,” offers a glimpse into an internal homesick mind scape, “The post office is closest to home / closest to my father’s stomach problems / closest to my brother’s school // on Sunday, we gather in the post office / lining up in front of money orders of a month of sweat / listening hard talking hard.” His sobering “Work Accident Joint Investigative Report,” recounts what people reported about an incident where a worker’s finger was accidentally cut off, “people reported after it happened she / didn’t cry and didn’t / scream she just grabbed her finger / and left // When it happened no one / was there to see it” — the range, here — from the slippery to the symbolic to the starkly literal, is a testament to the richness of voice and perspective. The “migrant laborer poet” is never just that.

In terms of the translation, the poems themselves don’t heavily play with language (or, at least, that’s not their primary concern. They don’t suspend themselves between cultures in a way that would necessitate experimentation and reinvention. One of the strengths of this collection is that the stories of labor are strikingly universal and transferable and the poems in translation deliver the physical and emotional ramifications of the subjects they depict with utilitarian grace. Each poem maintains a distinct voice, a tenor specific to its mission, a testament to effectively translating intention. In Xiangnan’s poem, “Production, in the Middle of Production, Is Soaked by Production,” lines like “a pile of mouths, partly parched,” show an obvious sonic consideration for an emphasis on the P sound, to echo the title, and repetitions of L and R sounds (“a row of footprints, trampling other bodies. scratching”) throughout, show the deliberate choices made in the English translations. In the same poem, lines like “When I lightly touch my own hair / passing by the truncated street of midnight / I discuss paper airplane wings / with someone, some fat guy / along with his fear” reveal a great deal in translation — the use of a word like “truncated” instead of “shortened,” connotes a cramped, crunched feeling, with a deep and heavy sound that then gets juxtaposed with the visual of a light paper airplane (then echoes back with the image of the fat man). This anthology is peppered with resonant choices like this one, which make translators like Eleanor Goodman absolutely essential to bringing forth the humanity and nuance amongst these voices. Her careful and thoughtful translation makes visible, palpable, and distinct, the lives, minds, and hearts of those kept unseen, whose labor we global citizens encounter and engage with on a daily basis.

Leave a Reply