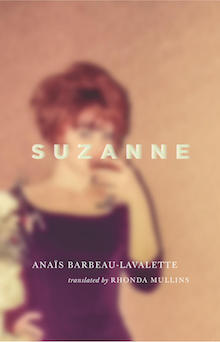

“Suzanne” by Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette [Why This Book Should Win]

The Why This Book Should Win entry for today is from literary translator Peter McCambridge, fiction editor at QC Fiction (a new imprint of the best of contemporary Quebec fiction in translation) and founding editor of Québec Reads.

Suzanne by Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette, translated from the French (Québec) by Rhonda Mullins (Canada, Coach House Books)

Every afternoon, Marcel works with his uncle at the butcher’s.

His hands in the red flesh, he strikes blows with the knife, cutting at just the right place, slashing what was formerly alive to give it a new shape, one of his own making. He doesn’t overthink it and moves instinctively.

It’s hard not to see the parallels with the author’s own creative process as she imposes her will on this fictionalized account of her grandmother’s life. Suzanne was the maternal grandmother she barely knew. The first time she saw her, she was one hour old. The second time, she was ten. And the third and final time came when she was 26 and Suzanne wouldn’t say why she left. Barbeau-Lavalette hired a private detective to piece together her life, to tremendous literary effect.

“Now, there is her, there is you, and between you, there is me,” the narrator writes, asking, “How could you just walk away? How did you not perish at the thought of missing her nursery rhymes, her little-girl lies, her loose teeth, her spelling mistakes, her laces tied all by herself, then her crushes, her nails painted then bitten, her first rum-and-Cokes?”

The prose is careful and weighted, delightful. It sparks into life on page 15:

You had to die for me to take an interest in you.

For you to turn from a ghost to a woman. I don’t love you yet.

But wait for me. I’m coming.

It seems reductive, it seems too obvious to mention, but Suzanne is on the BTBA longlist because it’s beautifully written.

It begins in working-class Ottawa in the 1930s, the men “coming home from the factory with heavy hands and empty stomachs.” It’s cold and people are hungry in their hand-me-down shoes. We see the country’s first slums, there is no gas left for the cars, English mixes with French on the streets. Soon, Canada is at war, but people aren’t scared yet. Family stories share paragraphs with world history as the author invents conversations, everyday events, tics, and details to paint her portrait.

The language is nothing short of gorgeous, the turns of phrase and images memorable as Mullins’ steady hand ensures they all work equally well in English, served by an elevated register of French that comes across as poetic and earnest and vivid in this context.

Suzanne is 18 and off to study in Montreal. Talk turns to “systems of thought and worlds to invent.” There’s provincial and Canadian history, too, a swirl of references to the Duplessis government, L’Action catholique newspaper, and the launch of the Refus global manifesto, context for which is provided in translator’s notes at the end. Banned books, Automatism, and dinner parties (“You have a life. You wear it like a thin disguise.”) file by, Suzanne a “tightrope walker on the wire of history” as she abandons her family, puts her kids up for adoption, and moves to rural Gaspé, to Brussels, to England, to Harlem as it goes up in flames, to Alabama and the Ku Klux Klan.

What on the face of it is no more than fictionalized biography (I have a very limited interest in other people’s lives) is held together by such beautiful writing and pacing that the whole thing just works. Much like Éric Plamondon’s 1984 series of fictionalized biographies of Johnny Weissmuller, Richard Brautigan, and Steve Jobs might in other hands have read like a procession of facts to be checked off, a late-night binge of Wikipedia articles, the fact and fiction is combined here with such artistry and precision that the reader cannot help but be impressed. This is prose to lose yourself in. Never complicated, it’s gentle like a love song, comforting and enveloping like a black and white film, full of tones and textures. These sentences can destroy us. Not for their simplicity, but for the powerful beauty within the simplicity:

You are falling and you don’t know when it will stop.

This deftness of touch made La femme qui fuit a very good book, a critical and popular success both in Québec and France. Now Rhonda Mullins’ sensitive translation makes it a worthy inclusion on the BTBA longlist.

[…] translated by Rhonda Mullins. A finalist for last year’s BTBA (Peter McCambridge wrote the Why This Book Should Win post), this book is about a relationship between a woman and her grandmother . . . but it’s written in […]