Letters

(Photo: Rochester Review)

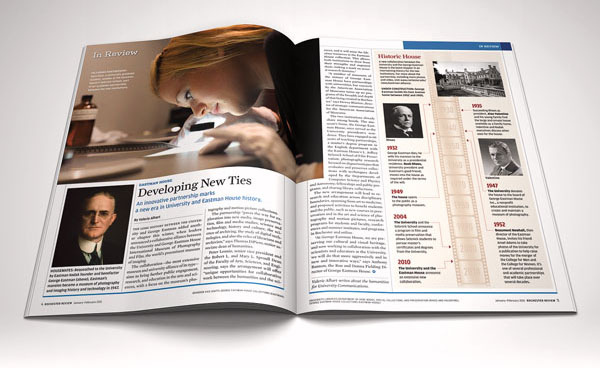

(Photo: Rochester Review)Photographic Memories

As one of the few interdepartmental film studies majors in my graduating class at the University, my reaction to the University’s alliance with the George Eastman House (“Developing New Ties,” In Review, January-February) was, “What took so long?” A close collaboration between the two institutions has long seemed to me to be a no-brainer, and I can only assume that a combination of internal politics and budgetary considerations were what led to the long delay.

The presence of the George Eastman House in Rochester was one of the prime reasons I attended the University (I turned down both Cornell and Johns Hopkins to attend, much to my upwardly mobile parents’ chagrin), and I benefited mightily from the resources I was able to access at the Eastman House. Younger people forget how difficult it was to study film in those pre-VCR/DVD days. In my freshman preceptorial, for example, Professor Richard Gollin showed Resnais’s Hiroshima Mon Amour to the class. In order to do this, he had to drag a bulky video camera and wide-tape reel-to-reel video recorder home, point the camera at the TV, and record from a PBS broadcast. Needless to say, the class was not able to appreciate his comments on the differences in film stock used in the various scenes.

In this virtually prehistoric environment, the George Eastman House provided a unique opportunity for those of us interested in film. The archivists Jim Card and Marshall Deutelbaum ’78 (PhD) who taught courses were able to access the full resources of the archive to highlight points they wanted to make in class. For example, when we studied Carl Dreyer, Card did not merely show a copy of The Passion of Joan of Arc; he also pulled a couple of earlier Dreyer silent films from the vaults (Leaves from Satan’s Book and Master of the House) to make a point. In our film history course, instead of showing John Ford’s Stagecoach, Deutelbaum substituted Ford’s recently rediscovered 1917 film Straight Shootin’ (with Czech inter-titles, if I remember correctly) and pointed out similarities between that film and Ford’s later classic The Searchers. (In order to encourage us not to miss classes, Deutelbaum also showed an episode of the 1940s B-serial King of the Rocketmen before each class; we eagerly looked forward to the resolution of each cliff-hanging ending to the episode at the next week’s class.)

But the highlight of my time at the U of R was getting permission to do an independent research course my senior year on American silent film, something an undergraduate probably would not have been able to do at any other university in the world. Each week, I would sit alone in the Dryden Theatre, seeing forgotten masterpieces of American cinema—films such as Karl Brown’s quasi documentary Stark Love, John Collins’s technically advanced melodrama Blue Jeans, Monta Bell’s Oedipal film Man, Woman and Sin (with Jeanne Eagels), Paul Fejos’s part-soundie Lonesome and Howard Hawks’s buddy movie A Girl in Every Port (in a nitrate print—the screen positively glowed when it was projected). I also got the opportunity to meet silent film actors such as Blanche Sweet (whose film career started with D. W. Griffith in 1909) and Viola Dana (a latecomer compared to Sweet, she apparently didn’t start making films until 1913). But the highlight of that course was when I showed up one afternoon and Deutelbaum told me there had been a change of plans because a visitor wanted to see a Louise Brooks sound film. He then proceeded to introduce me to author Christopher Isherwood, and Mr. Isherwood and I spent the afternoon together in the Dryden Theatre watching Brooks light up the screen in a virtually unknown French language film titled Prix de Beaute. (I still remember the song she sang in the film—“Ne Soit Pas Jaloux” or “Don’t Be Jealous.”)

Christopher Isherwood and Louise Brooks—pretty heady company for a 19- year-old undergraduate!

Brett Gold ’77

New York, N.Y.

I am pleased to see that the University is beginning to embrace photography and is developing an innovative partnership with the Eastman House. Some 60 years ago when the then curator of photography at the house, Beaumont Newhall, offered to teach a course in the history of fine art photography, he was turned down by the art department.

Richard Zakia ’70W (EdD)

Apex, N.C.

A Diversity Challenge

I have just finished reading President Joel Seligman’s article about Esther Conwell and her amazing life and career as a woman in the sciences (“Esther Conwell’s Inspiring Example,” President’s Page, January-February.) She is a true pioneer. It’s difficult to imagine the barriers she faced just 60 years ago.

As a parent of a U of R first-year student, I am gratified to see a genuine commitment to diversity, with meaningful numbers of women on the faculty and in leadership positions. However, I would challenge the University to define diversity to include employment of individuals with disabilities in meaningful numbers. I work daily with people with disabilities, many of whom leave college and graduate school with high honors and big dreams, only to face terrible discrimination and unemployment. It does require creativity and perhaps some technology to accommodate those with disabilities, but just as with women, the benefits are innumerable. When the number of individuals with disabilities at the University increases, students will see professors who happen to be blind, a wheelchair user, or an individual who is deaf or hard of hearing, as the norm. They will also expect to see them in the workplace after they graduate.

I wish the University well in its continued efforts toward diversity, and look forward to seeing more individuals with disabilities in the coming years.

Margo Druschel

Mankato, Minn.

The author is the parent of Henry Druschel ’14.

Cost of College?

Few people would dispute the overall value of a college education (“Education Pays,” President’s Page, November-December 2010). The real and more valid question we should be asking is whether it’s legitimate to saddle new graduates with years of debt in service of that education. Unfortunately, President Seligman’s numbers just don’t add up.

The College Board study, and the numbers that President Seligman cites from it, focus on medians—the statistical point that divides a population in half. According to the College Board’s Trends in College Pricing 2010 study, the tuition and fees at a private, four-year institution average $37,000, and for a public institution at in-state rates, the average is $16,000. While Rochester is a university significantly above the median in educational performance, it’s also clearly well above the median in tuition: $51,000 and rising. This places Rochester in the top four-tenths of 1 percent of all academic institutions with respect to tuition.

President Seligman depicts the average student (who makes $55,700 at age 25)paying off their loans by age 33. Unless we believe that salary point is much, much higher for Rochester graduates—for which President Seligman presents no evidence—I have a hard time believing that students will shed their debt burden that early, unless they are lucky enough to choose the one or two careers that are in vogue at that point in time.

Furthermore, we should not be patting ourselves on the back regarding the fact that our alumni spend the first decade or more of their working careers servicing their educational debt. This is a time at which most people are starting families and trying to establish their independent lives. We should be striving to ensure that Rochester educates the next generation of students to the highest of standards in a liberal arts environment, regardless of their degrees, and does not drive them to the poorhouse in the process.

Sean Colbath ’90

Winchester, Mass.

Love of Lizards

I never studied the evolution of Caribbean lizards (“Lizard Lessons,” In Review, January-February), but I did have considerable association with them in the 1960s and ’70s while visiting my in-laws in Santurce, Puerto Rico. Their porch was bounded by a low brick wall and a wrought-iron grill work.

On the porch in the morning I would read from Beat the Market, a popular investment book at the time. The first day a single lagartijo, as they were called in Spanish, appeared on the grill and watched me read. When I left the porch, he also left. The second day, two of these little guys showed up and repeated the process. Each day another lagartijo was added until I think there were five or six of them. Obviously these were the forerunners of the lizards of Wall Street.

In the evening I often watched a portable TV placed on the brick wall. A single lagartijo appeared on the wall beside me. When I pointed out a bug on the wall, he ran over and digested it. One night he decided to find out who all those people were in the TV picture, so he ambled over to the TV and explored it completely, trying to find out how to get to those people in the box.

Needless to say, I have been a fan of Caribbean lizards ever since. They seem to possess a connection with humans similar to that of dolphins, although the lizards avoid being touched.

Walton Howes ’48

Middleburg Heights, Ohio

Review welcomes letters and will print them as space permits. Letters may be edited for brevity and clarity. Unsigned letters cannot be used. Send letters to Rochester Review, 22 Wallis Hall, P.O. Box 270044, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY 14627-0044; rochrev@rochester.edu.