Frances Riddle Reading Martín Felipe Castagnet [Granta]

In addition to a series of posts about the 25 pieces in the new Granta, I asked a handful of the translators to provide short videos introducing the piece they worked on for the issue and reading a section from it. Up today is Frances Riddle, who translated Martín Felipe Castagnet's "Our Windowless Home." ...

>

Polish Reportage [#WITMonth]

Starting in 2021, Open Letter will be launching a "Polish Reportage" series. This came out of a trip I made to Krakow back in 2017 (when the Astros cheated their way to a World Series, which, remember when that mattered?) to attend the Conrad Festival and meet with a variety of authors, editors, and the like. I've always been ...

>

Three Percent #178: This Podcast Is Not Contagious

Today's episode is all about small presses. Chad and Tom breakdown, discuss, elaborate on, and praise, Matvei Yankelevich's recent Poetry post 'The New Normal: How We Gave Up the Small Press." This is a rather wide-ranging conversation about grant applications, distribution for small presses, AWP, professionalization, how ...

>

Three Percent BONUS EPISODE: Antonia Lloyd-Jones and Sean Bye on Polish Reportage

As part of Nonfiction in Translation Month at Three Percent, Polish translators Antonia Lloyd-Jones and Sean Bye came on the podcast to explain Polish Reportage, talk about some key figures and forthcoming books, and more or less introduce Open Letter's new nonfiction line. Some of the titles mentioned on this podcast ...

>

“Ebola 76” by Amir Tag Elsir [Why This Book Should Win]

Today’s first entry into the Why This Book Should Win series is from Riffraff co-owner, Three Percent podcast co-host, and French translator, Tom Roberge. Ebola 76 by Amir Tag Elsir, translated from the Arabic by Chris Bredin and Emily Danby (Sudan, Darf Publishers) Sudanese writer (and doctor) Amir Tag Elsir’s ...

>

Three Percent #135: Polish Reportage and a Lot of Sci-Fi Talk

After discussing the incredibly long Dublin Literary Prize longlist, Chad and Tom discuss Polish Reportage, Stanislaw Lem’s book covers, ordering books for Riffraff, and a serial killer. UPDATE: Here’s a link to all of the new Polish Lem covers. And the one for His Master’s Voice. This week’s ...

>

“French Perfume” by Amir Tag Elsir [Why This Book Should Win]

This entry in the Why This Book Should Win series is by Najeebah Al-Ghadban. We will be running two (or more!) of these posts every business day leading up to the announcement of the finalists. French Perfume by Amir Tag Elsir, translated from the Arabic by William M. Hutchins (Sudan, Antibookclub) It may be ...

>

2013 Susan Sontag Prize for Translation

The 2013 Susan Sontag Prize for Translation was just announced, with Nathaniel Rudavsky-Brody receiving this year’s honors for his translation of Benjamin Fondane’s Ulysse. Not much info up on the Sontag site yet, although I think this literally just went online. (I’ve been refreshing that page like a ...

>

Susan Sontag 2012 Prize for Translation

The Susan Sontag Foundation recently announced Julia Powers and Adam Morris as the winners of their 2012 Prize for Translation. Every June, the $5,000 prize is awarded to a literary translator under the age of 30 over the course of five months, during which the proposed project must be completed. The award was established to ...

>

"Upstaged" by Jacques Jouet [25 Days of the BTBA]

As with years past, we’re going to spend the next three weeks highlighting the rest of the 25 titles on the BTBA fiction longlist. We’ll have a variety of guests writing these posts, all of which are centered around the question of “Why This Book Should Win.” Hopefully these are funny, accidental, ...

>

Juan Gabriel Vasquez's "The Secret History of Costaguana"

This may be thanks to Bolano and his massive appeal, but it seems (to me at least), like Spanish literature is going through a sort of a “Second Boom.” Not so much in terms of a shared aesthetic, but in terms of having captured the imaginations of American publishers. In addition to standards like Javier Marias ...

>

On Translating for the Stage

Click here for Joanne Pottlitzer’s introduction to her essay. This piece was delivered last month at an event at the Americas Society in NYC. It is my pleasure to share a few words with you on translating for the stage and on the journey of translating José Triana’s Palabras comunes. One of the ongoing debates ...

>

Intro to "On Translating for the Stage"

Jon Peede, formerly of the NEA, put Joanne Pottlitzer in touch with me in hopes that we could help publicize her recent essay “On Translating for the Stage.” The essay—which will go up in about 10 minutes—is very interesting, and discusses one of the singular challenge of translating drama. In order to ...

>

PEN: Get Super Lit: Comic Books Come Alive on Stage

Where: The Cooper Union, Frederick P. Rose Auditorium, 41 Cooper Sq., New York City Critics like to point out “comic books are not just superheroes,” that they’re also heartrending memoirs, important nonfiction, and even avant-garde art. True. But you can’t throw this baby out with the bathwater because it’s got ...

>

2011 Susan Sontag Prize for Translation [Young Italian Translators]

I’ve been meaning to post this for a month now . . . At least there’s still some time before the March deadline: THE 2011 SUSAN SONTAG PRIZE FOR TRANSLATION $5,000 grant for a literary translation from Italian into English: PLEASE POST & DISTRIBUTE PLEASE NOTE: The deadline is March 1, ...

>

Susan Sontag Prize Award Winners

Another day, another post that should’ve been written weeks ago . . . (In case you haven’t noticed, today is themed. And this extends beyond the blog to responding to dozens of e-mails I should’ve responded to way back when.) Last month, the Susan Sontag Foundation announced that Benjamin Mier-Cruz won the 2010 award ...

>

Genres, Tags, and Why Don't We Subcategorize Books?

Today’s piece in the New York Times on indie rock sub-categorization isn’t particularly interesting . . . although when you apply what’s been happening in music to the world of books, there are a few intriguing outcomes. The main thrust of Ben Sisario’s Times piece is that indie music has atomized ...

>

Susan Sontag Foundation Crushes on My Crushes

The call for submissions for the 2010 Susan Sontag Prize for Translation was posted last week, and this year the focus is on translations from Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, and Icelandic. This prize was launched two years ago to encourage the development of young literary translators. Applicants must be under the age of 30 ...

>

Susan Sontag Award: Year Two

I don’t think I received a press release about this, but the 2009 Susan Sontag Prize for Translation has been awarded to Roanne Sharp for her proposed translation of La Mayor by Juan Jose Saer. Which is fantastic—we’re actually publishing three Saer books over the next few years, but not this one. . . . At ...

>

Sebald on Stage

Thanks to Conversational Reading (and Vertigo before that) for bringing “i-witness” to our attention. From Wales Online Like most of us, Paul Davies and Fern Smith enjoy immersing themselves in a good book. [Ed. Note: That use of “like most of us” signals that we’re not reading a U.S. ...

>

Susan Sontag Translation Prize

The Susan Sontag Foundation recently released information about their 2009 translation prize, this time awarding young translators working on Spanish into English projects: This $5,000 grant will be awarded to a proposed work of literary translation from Spanish into English and is open to anyone under the age of 30. The ...

>

Susan Sontag Prize for Translation

We posted about the Susan Sontag Prize for Translation when the call for submissions went out, and it was just announced that Kristin Dickinson (who did her undergrad work at the University of Rochester), Robin Ellis, and Priscilla Layne won for their collaborative translation of Koppstoff: Kanaka Sprak vom Rande der ...

>

2008 Susan Sontag Prize for Translation

We actually posted about the Susan Sontag Prize for Translation back before Three Percent went live, but with the deadline approaching, I think it’s worth bringing up again, especially since it’s such a cool prize. One of the first activities of the newly-established Susan Sontag Foundation, this Prize for ...

>

Hispanic Heritage Month Reading Program

From GalleyCat The Association of American Publishers announced that it has joined forces with Las Comadres Para Las Americas, an informal internet-based group that meets monthly in over 50 US cities and growing, to build connections and community with other Latinas, to launch Reading with Las Comadres. The program is ...

>

Two Month Review Season 23: “Lanark” by Alasdair Gray

Before we get into the selection for next season, I want to remind everyone to vote in our poll for the Best TMR Class. The hypothetical is that you have to sign up for one of these courses being offered based on the books included. "Let the Bodies Hit the Floor" Death in Spring by Mercè Rodoreda; The Physics of ...

>

TMR 22.4: “Devotion to Off-Grid Religions” [Praiseworthy]

Emmett Stinson (Murnane) joins Chad W. Post and Kaija Straumanis this week to educate us about Australian culture and literature and things we should keep in mind while reading Praiseworthy. He also participates in a round of the world-famous trivia game: "Australian Baseball Player or Indigenous Australian Writer?" There ...

>

A Venn Diagram of Not Reading

“If I actually finish a book, I feel like I deserve a Nobel Prize.” “I can't even guess when I last read a book. But I'd watch movies all day if I could. Especially Marvel ones.” Overheard on a University of Rochester Shuttle “In the last decade, she says, history has toppled from the king of disciplines to a ...

>

Eleven Books, Selected

My parents are straight-up hoarders. Not of foodstuffs or other animal attractant stuff; nothing that will quite land them on a nightmare HGTV show (one that airs right after Flipanthropy), but hoarders nonetheless. Of paper, mostly. Checklists from the early 80s show up on the regular. I currently have a gym bag ca. 1993 ...

>

TMR 20.1: “Then You Do Not Approve of Nabokov?” [MULLIGAN STEW]

Chad and Brian kick off the new season in near hysterics over the first little chunk of Gilbert Sorrentino's Mulligan Stew. From talking about the rejection letters—and near batshit reader's report—prefacing the book, to all the bad writing about the "flawless blue" sky, to the ever-changing dialog tags in Anthony ...

>

“Vladivostok Circus” by Elisa Shua Dusapin & Aneesa Abbas Higgins [Excerpt]

Today's #WITMonth post is a really special one—with a special offer. What you'll find below is an excerpt from the very start of Vladivostok Circus by Elisa Shua Dusapin & Aneesa Abbas Higgins. You might remember Dusapin & Higgins as the winners of the 2021 National Book Award for Literature in Translation ...

>

“The Lecture” by Lydie Salvayre and Linda Coverdale [Excerpt]

Today's #WITMonth post is an excerpt from The Lecture by Lydie Salvayre, translated by Linda Coverdale, a wonderfully funny and playful French writer who Dalkey published for quite a while (The Power of Flies, Everyday Life, The Company of Ghosts, Portrait of the Writer as a Domesticated Animal), and might again! Warren ...

>

Season Twenty of the Two Month Review: “Mulligan Stew” by Gilbert Sorrentino

As mentioned in this Reading the Dalkey Archive post, Mulligan Stew by Gilbert Sorrentino is going to be the next book featured on the Two Month Review podcast. For anyone new to this podcast, episodes drop weekly—recorded live on YouTube, then disseminated as a traditional podcast through Apple, Spotify, etc.—and ...

>

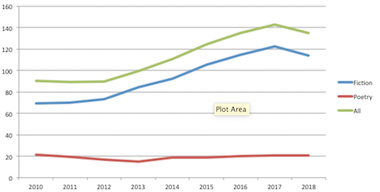

The Visual Success of Women in Translation Month [Translation Database]

Women in Translation Month is EVERYWHERE. Whenever I open Twitter (or X?), my feed is wall-to-wall WIT Month. Tweets with pictures of books to read for WIT Month, links to articles about WIT Month and various sub-genre lists of books to read during WIT Month, general celebratory tweets in praise of Meytal Radzinski for ...

>

Anatomy. Monotony. [Reading the Dalkey Archive]

Anatomy. Monotony. Edy Poppy Original Publication: 2005 Original Publication in English Translation: 2018 Original Publisher in English: Dalkey Archive Press Although I’m filing this as a “Reading the Dalkey Archive” post, it’s actually about two books: Anatomy. Monotony. by Norwegian ...

>

Re-Reading David Markson’s “Wittgenstein’s Mistress”

This piece by Philip Coleman first appeared in CONTEXT #23. To celebrate the recent release of Wittgenstein's Mistress as part of the Dalkey Archive Essentials series, it seems like the perfect time to revisit this re-reading of David Markson's classic novel about language, memory, grief, and possibly the end of the ...

>

“Not Even the Dead” by Juan Gómez Bárcena [Excerpt]

Officially out last Tuesday, Not Even the Dead is a throwback—an ambitious, philosophical, grand novel taking on nothing less than the history of progress over the past four hundred years. In it, Juan—at the bequest of the Spanish government—pursues "Juan the Indian" across time and Mexico, almost catching up to him ...

>

“Europeana” by Patrik Ouredník [Excerpt]

Forthcoming in a new "Dalkey Essentials" edition, Europeana: A Brief History of the Twentieth Century is an "eccentric overview of all the horrors, contradictions, and absurdities of the past century." It's a book that is mesmerizing in its curious patterns, which at times can sound like Snapple Fun Facts—but tend to be ...

>

Ryder [Reading the Dalkey Archive]

Ryder Djuna Barnes Original Publication: 1928 Original Publisher: Boni & Liveright First Dalkey Archive Edition: 1990 This is a baggy novel of excess, and as someone who finds it nearly impossible to keep the thread—or develop a coherent thesis (any and all AI grading systems ...

>

“Diary of a Blood Donor” by Mati Unt [Excerpt]

Diary of a Blood Donor by Mati Unt translated from Estonian by Ants Eert (Dalkey Archive Press) AN UNEXPECTED INVITATION A crow was riding the wind that came in low over the beach. Sand blew through the window, landed on my papers, entered my mouth. A yellowish light tainted the room, even my ...

>

Mati Unt (1944-2005)

This piece originally appeared in CONTEXT 18, shortly after Mati Unt's passing. It was written by the translator Eric Dickens, Unt's translator, who also left us in 2017. Mati Unt was born in Estonia and lived there all his life. He spent his early years in the village of Linnamäe near the university town of Tartu. His ...

>

Zoo, or Letters Not about Love [Excerpt]

Forthcoming in a new "Dalkey Archive Essentials" version (with a different cover than the one depicted to the right), Zoo, or Letters Not about Love, translated from the Russian by Richard Sheldon, is one of Viktor Shklovsky's most beloved works. An epistolary novel written while Shklovsky was in exile in Berlin—and in ...

>

Perfect Lives [Reading the Dalkey Archive]

Perfect Lives Robert Ashley Original Publication: 1991 Original Publisher: Archer Fields Press First Dalkey Archive Edition: 2011 Let’s start with the cover. When this first arrived in the mail, I was certain that Ingram had sent it to me on accident. It looks nothing like ...

>

An Echo Chamber of One [Sustainability]

Hello! I am ChadGPT, an AI chat generator that has been asked to produce a blog post in the style of Chad W. Post, about the future of publishing. After ingesting over a thousand articles from this website, literally hundreds of thousands of (mostly coherent) text messages, and zero email responses (apparently Chad is 100% ...

>

To All the Posts I Didn’t Write Last Year

If I could control space-time (a resolution for 2023 that's about as likely as the others I've made), I would have put in an additional 10 hours of research and data entry into the Translation Database before posting this. But knowing that I'll surely be crunched for time all this week, and next, and the week after, I figure ...

>

Time Must Have a Stop

I haven't been feeling much like myself lately. Doubt anyone has, what with COVID time making everything take twice as long and be four times as frustrating, with Putin being, well, a massive, invasive dick, with inflation the highest it's been since I was five years old, and with no spring baseball. [UPDATE: Baseball is ...

>

TMR 16.1: “Roberto Bolaño Overview” [2666]

Season 16 is here! At long last, Bolaño's 2666 takes center stage, and Chad and Brian are joined by translator and Bolaño enthusiast, Katie Whittemore. In this opening episode, they discuss the myth-making of Bolaño's biography, they talk about sudden fame, the grind of the artist, and of the way that everything is ...

>

Translation Jobs [Granta]

Following on the first two posts about the latest Granta issue of "Best Young Spanish-language Novelists," I thought I'd take another crack at trying to define success, this time through the lens of the translators included in the two issues. This might be the most controversial approach to date (I do have two more that ...

>

“Last Words on Earth” by Javier Serena and Katie Whittemore [Excerpt]

Last Words on Earth by Javier Serena, translated from the Spanish by Katie Whittemore (September 21, 2022) Eventually, the professor redirected the conversation toward more exotic subjects: he asked Funes to tell me about negacionismo, a poetic movement Funes had apparently founded as an adolescent in Mexico, where he ...

>

Statistical Noise [Granta]

It took a few more days than I had hoped, but I have officially read all twenty-five pieces included in this new Granta issue. (I wonder how many people actually do read it from cover to cover. And what percentage that is of all the copies in circulation. God, I'll bet that number is depressing, whether it's Granta, ...

>

The Predictive Success of Listmaking [Granta]

Let's start by saying what really shouldn't need to be said: Being included in one of Granta's "Best Young XXX Novelists" special issues is an incredible honor. These come out once a decade, with four iterations of "best young" British novelists, three for American writers, and, as of this month, two for Spanish-language ...

>

Writing about Granta’s “Best of Young Spanish-Language Novelists 2”

Just about a decade ago, Granta released their first ever list of "young Spanish-language novelists." This was a momentous occasion for a number of reasons, starting with the point that, until then, only young British and American writers had been featured by the magazine. (There had been three lists of best British ...

>

The Hole vs. The Hole vs. Algorithms vs. Booksellers

Although it's still hard to get truly excited about writing—and harder to imagine anyone reading this, given all that's going on in the world—it was pretty fun working on that last post about October titles that I wish I had the time and attention to read. So, why not do it again? Even if these posts are shambolic and ...

>

Why I Haven’t Written Any of My Posts

The other night, when I first attempted to write this post, I was shocked to find that the last "real" post I'd written (the nutty Baudrillard in the Time of COVID/Baseball is Back! experiment), posted on July 29th. July! That was almost three months ago. Where did the time go? And why haven't I written anything since ...

>

TMR 13.5: “The Accursed Children” [ADA, OR ARDOR]

A family dinner, a picnic in the woods—what could be more innocent? Well, in Ada, or Ardor, everything is tinged with a baseline feeling of "kind of creepy," especially the "passionate pump-joy exertions." Chad and Brian break it all down, talking about Demon, unraveling Nabokovian puns, finding subtle hints about Van's ...

>

Five Questions with Michael Holtmann about HOME

As part of our ongoing series of short interviews featuring the people who helped bring great new translations to the reading public, we talked to Michael Holtmann, the executive director and publisher of the Center for the Art of Translation and Two Lines. Before getting into the interview, I wanted to point out ...

>

“The Adventures and Misadventures of the Extraordinary and Admirable Joan Orpí, Conquistador and Founder of New Catalonia” by Max Besora and Mara Faye Lethem

In honor of the Catalan Fellowship organized by the Institut Ramon Lllul and taking place virtually this week, I thought I would share the opening of next Catalan title to come out from Open Letter: The Adventures and Misadventures of the Extraordinary and Admirable Joan Orpí, Conquistador and Founder of New Catalonia by Max ...

>

TMR Season Thirteen: “Ada, or Ardor” by Vladimir Nabokov

The public has spoken, and the next book to be featured in the Two Month Review is Ada, or Ardor by Vladimir Nabokov! Which is kind of perfect. We follow the thread of Anna Karenina from The Book of Anna by Carmen Boullosa to this novel, originally written in 1969, which opens: "All happy families are more or less ...

>

Spanish-Language Speculative Fiction by Women in Translation. [#WITMonth]

Today's post is by Rachel Cordasco, founder and curator of Speculative Fiction in Translation, co-translator of Creative Surgery by Clelia Farris, and is working on a book about speculative fiction from around the world. Despite 2020 being a downright awful year, it has given us several excellent works of ...

>

New Spanish Literature: 10 of 30 [#WITMonth]

As part of the buildup to being Guest of Honor at the Frankfurt Book Fair 2021, the Spanish government launched a program last year under the (possibly confusing) name of "10 of 30." The plan is that each year, a new anthology featuring ten authors in their 30s will be released—all of which are translated by Katie ...

>

A Very Incomplete List of Books by Women in Translation in 2020 [#WITMonth]

I know that I'm a day behind—trying to make up for that right now—but my goal for Women in Translation Month 2020 is to post something each and every day of the month related to this topic. I'm inviting any and all readers, translators, publishers to contribute to this and, with a lot of luck a bit of work, we should have ...

>

Baudrillard in the Time of COVID / Baseball Is Back!

There are two types of people who read these posts: people into international literature who like baseball, and those who don’t. What follows is an experiment—one that might not work at all. Before you get started, you have a choice: 1) if you hate genuine writing about baseball, then click here, where I’ve edited ...

>

Baudrillard in the Time of COVID

There’s never been a better time to read Baudrillard. There’s also never been a worse. Thanks to quarantine, the unprecedented nature of this situation, Trump, government response to the protests—everything feels like an illusion. Not an illusion in the sense that “nothing is physically realm,” although one could ...

>

Baseball Is Back!

The other day, the Major League Baseball season—or, rather, “season,” given that it’s 60 games; given that instead of ten teams making the playoffs, sixteen will, which is more than half the league; that every extra inning starts with a runner on 2nd base, which is very weird; and, obviously, COVID protocols and a ...

>

“La vita bugiarda degli adulti” by Elena Ferrante

La vita bugiarda degli adulti by Elena Ferrante 283 pgs. | pb | 9788833571683 | €19,00 edizioni e/o Review by Jeanne Bonner If all had gone as planned—which is to say if a global pandemic hadn’t bulldozed our normal lives—this summer, you might have been reading Ann Goldstein’s English translation of La vita ...

>

“The Erotics of Restraint: Essays on Literary Form” by Douglas Glover

The Erotics of Restraint: Essays on Literary Form by Douglas Glover 203 pgs. | pb | 9781771962919 | $21.95 Biblioasis Review by Brendan Riley The Erotics of Restraint is an excellent companion—with a no less provocative title—to Mr. Glover’s previous collection, Attack of the Copula Spiders, published in ...

>

Nothing Adds Up Until You Overthrow the System

It's weird trying to write this today, May 31st, with all that's going on across the country—and around the world—right now. The images of our overly-militarized, super aggro, disgusting police officers running unarmed people over, throwing women to the ground, shooting teenagers with pepper balls and rubber bullets (that ...

>

“The Cheffe: A Cook’s Novel” by Marie NDiaye [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Marcel Inhoff is completing a doctoral dissertation at the University of Bonn. He is the author of the collection Prosopopeia (Editions Mantel, 2015), and Our Church Is Here (Pen and ...

>

“The Wind That Lays Waste” by Selva Almada [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Pierce Alquist has an MA in Publishing and Writing from Emerson College and currently works in publishing in Boston. She is a freelance book critic and writer. She is also the ...

>

Three Percent #182: BTBA 2020 Readings

On this special edition of the Three Percent Podcast, you can hear short readings of all fifteen finalists for this year's Best Translated Book Awards. You can find all of the titles here on Bookshop.org (fiction, poetry), and you can still RSVP to see the live awards ceremony on Friday, May 29th at 6pm eastern. This ...

>

“Beyond Babylon” by Igiaba Scego [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Barbara Halla is an Assistant Editor for Asymptote Journal. She works as a translator and independent researcher, focusing in particular on discovering and promoting the works of ...

>

“Aviva-No” by Shimon Adaf [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Adriana X. Jacobs is the author of Strange Cocktail: Translation and the Making of Modern Hebrew Literature (University of Michigan, 2018) and associate professor of modern Hebrew ...

>

“The Boy” by Marcus Malte [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Lara Vergnaud is a literary translator from the French. She was the recipient of the 2019 French Voices Grand Prize and a finalist for the 2019 BTBA. Her work has appeared in The ...

>

“The Catalan Poems” by Pere Gimferrer [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Henry N. Gifford is a writer, emerging translator from German to English, and Assistant Editor at New Vessel Press. The Catalan Poems by Pere Gimferrer, translated from the ...

>

“Space Invaders” by Nona Fernández [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Chris Clarke grew up in Western Canada and currently lives in Philadelphia. His translations include books by Ryad Girod, Pierre Mac Orlan, and François Caradec. His translation of ...

>

. . . The Underappreciated Masses . . .

Half of this post is inspired by comments Sam Miller made about this article he wrote about the mystery surrounding Don Mattingly's birthdate and his Topps 1987 baseball card. I'm not sure if these are immutable truths per se, but if you talk to enough people in the book industry, you're likely to encounter two strains of ...

>

We’re Still Here . . .

"We live in a world of randomness." —William Poundstone, The Doomsday Calculation It probably goes without saying, but publishing international literature is a precarious business in the best of times. On average, sales for translated works of fiction tend to be about one-third of the average sales for a mid-list author ...

>

“The Next Loves” by Stéphane Bouquet [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Laura Marris is a writer and translator from the French. Recent projects include Paol Keineg’s Triste Tristan (co-translated with Rosmarie Waldrop for Burning Deck Press) and In ...

>

Three Percent #181: Unraveling Women and Hard-Working Peasants

A bit of an experimental episode, Chad is joined by five indie booksellers to talk about the "new normal," fears of reopening, what booksellers are doing now, and—most importantly—actual books. The complete rundown of recommendations is below, but one note: please buy these titles from the bookseller who recommended them. ...

>

“Territory of Light” by Yuko Tsushima [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Kári Tulinius is an Icelandic poet and novelist. He and his family move back and forth between Iceland and Finland like a flock of migratory birds confused about the whole “warmer ...

>

“The Way Through the Woods” by Long Litt Woon

The Way Through the Woods by Long Litt Woon Translated from the Norwegian by Barbara J. Haveland 320 pgs. | hc | 9781984801036 | $26.00 Spiegel & Grau Review by Hana Kallen How does one heal after the death of a loved one? How does define oneself again after tragedy? Author and anthropologist Long Litt ...

>

“The Book of Collateral Damage” by Sinan Antoon [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Tara Cheesman is a freelance book critic, National Book Critics Circle member & 2018-2019 Best Translated Book Award Fiction Judge. Her work has appeared in the Los Angeles Review ...

>

The Winter Garden Photograph by Reina María Rodríguez [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Anastasia Nikolis recently received her PhD in twentieth and twenty-first century poetry and poetics from the University of Rochester. She is the Poetry Editor for Open Letter Books ...

>

“Vernon Subutex 1” by Virginie Despentes [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Dorian Stuber teaches at Hendrix College and blogs about books at www.eigermonchjungfrau.blog. His work has appeared in Numéro Cinq, Open Letters Monthly, and Words without ...

>

“Camouflage” by Lupe Gómez [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Kelsi Vanada is a poet and translator from Spanish and sometimes Swedish. Her translations include Into Muteness (Veliz Books, 2020) and The Eligible Age (Song Bridge Press, 2018), ...

>

“God’s Wife” by Amanda Michalopoulou

God's Wife by Amanda Michalopoulou Translated from the Greek by Patricia Felisa Barbeito 144 pgs. | pb | 9781628973372 | $16.95 Dalkey Archive Press Review by Soti Triantafyllou Why do people get married? Maybe because they need a witness to their lives, someone to watch them do whatever it is that they do. In Amanda ...

>

“Animalia” by Jean-Baptiste del Amo [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Jeffrey Zuckerman is an editor at Music & Literature and a translator from French, most recently of Jean Genet's The Criminal Child (NYRB, 2020). A finalist for the ...

>

“Good Will Come from the Sea” by Christos Ikonomou [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Julia Sanches is a translator working from Portuguese, Spanish, and Catalan into English. She has translated works by Susana Moreira Marques, Daniel Galera, Claudia Hernández, and ...

>

Three Percent #180: Bookfinity Is the Dumbest Name

Stacie Williams joins Chad and Tom this week to talk about the role of sales reps at this moment in time and then, after she bolts, Chad and Tom poke fun at Bookfinity (which, really, WOW), the confused messaging of #BooksAreEssential as a hashtag, why bookshops shouldn't open, and how Publishers Weakly is funny AND NOT RUN ...

>

“Welcome to America” by Linda Boström Knausgård [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Katarzyna (Kasia) Bartoszyńska is a former BTBA judge (2018 and 2017), a translator (from Polish to English), and an academic (at Monmouth College, and starting this Fall, at Ithaca ...

>

“Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead” by Olga Tokarczuk [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Louisa Ermelino is the author of three novels; Joey Dee Gets Wise; The Black Madonna (Simon and Schuster); The Sisters Mallone (St. Martin’s Press) and a story collection, ...

>

Three Percent #179: “Hey! What’s New?”

How is COVID-19 impacting bookstores, publishers, translators, and our general sanity? These are the questions Tom and Chad talk about on this episode—the first in a while, but also the longest ever—along with minor jokes, an appeal to authors and publishers to "read the room," a rant that will likely get Chad in ...

>

TMR 11.6: “Adaptations” [THE DREAMED PART]

Chad and Brian go deep into the underlying structure of the second section of Fresan's The Dreamed Part, talking about Penelope's story, her relationship to her parents and the Karmas, and the moment in which she lost her son. We finally get to read about her wrecking house (literally) and see how everything circles back to ...

>

“Death Is Hard Work” by Khaled Khalifa [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Tony Messenger is an Australian writer, critic and interviewer who has had works published in many places including Overland Literary Journal, Southerly, Mascara Literary ...

>

Lola Rogers on “The Colonel’s Wife” by Rosa Liksom [The Book That Never Was, Pt. 1]

The Colonel's Wife by Rosa Liksom, translated from the Finnish by Lola Rogers (Graywolf Press) BookMarks Reviews: Five total—Four Positive, One Mixed Awards: None Number of Finnish Works of Fiction Published in Translation from 2008-2019: 65 (5.42/year) Number of Those Translations Written by Women: 40 of the ...

>

“Labyrinth” by Burhan Sönmez [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Tim Gutteridge is a Scottish literary translator, working from Spanish into English. His translation of Miserere de cocodrilos(Mercedes Rosende) will be published later this year by ...

>

“Tentacle” by Rita Indiana [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Tobias Carroll is the author of the books Reel, Transitory, and the forthcoming Political Sign. Tentacle by Rita Indiana, translated from the Spanish by Achy ...

>

“A Dream Come True” by Juan Carlos Onetti [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Spencer Ruchti is an intern at Tin House Books and formerly a bookseller at Harvard Book Store in Cambridge. His writing has appeared in The Adroit Journal, The Rumpus, and ...

>

TMR 11.5: “Wuthering Heights Is Weird” [THE DREAMED PART}

Chad reaches a new quarantine low at the beginning of this week's episode (highly recommend checking out the video version), but after a lot of banter and deep dives into international speculative fiction, The Invention of Morel, Lost, and more, Chad and special guest Rachel Cordasco break down the first part of the ...

>

“Will and Testament” by Vigdis Hjorth [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Elisa Wouk Almino is a Los Angeles-based writer and literary translator from Portuguese. She is the translator of This House(Scrambler Books, 2017), a collection of poetry by Ana ...

>

“Book of Minutes” by Gemma Gorga [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Nancy Naomi Carlson is a poet, translator, and editor, whose latest book was called "new & noteworthy" by the New York Times. Recipient of two NEA literature translation grants ...

>

“The Memory Police” by Yoko Ogawa [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Tony Malone is an Australian reviewer of fiction in translation, whose site, Tony’s Reading List, has been providing reviews continuously since 2009. His main focus is on Japanese ...

>

“China Dream” by Ma Jian [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Justin Walls is a bookseller based in the Pacific Northwest and can be found on Twitter @jaawlfins. China Dream by Ma Jian, translated from the Chinese by Flora Drew ...

>

“Die, My Love” by Ariana Harwicz [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Josh Cook is the author of the novel An Exaggerated Murder, published by Melville House in March 2015. His fiction and other work has appeared in The Coe Review, Epicenter ...

>

“Time” by Etel Adnan [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards. Brandon Shimoda is the author of several books, most recently The Grave on the Wall (City Lights), which received the PEN Open Book Award, The Desert(The Song Cave), and Evening ...

>

TMR 11.4: “Tulpas” [THE DREAMED PART]

This episode got off to a rough start, with Chad losing his shit over the May IndieNext list [ed. note: he still has not recovered] before Streamyard crashed and the whole episode had to be recorded. In the new, much calmer episode, Chad, Brian, and special guest Patrick Smith talk about tulpas, the night, Fresán writing in ...

>

Season 11 of the Two Month Review: “The Dreamed Part” by Rodrigo Fresán

After a slightly longer hiatus than expected, the Two Month Review is coming back! In fact, we're coming back TOMORROW, Thursday, March 5th at 1:30pm. We'll be recording an introductory episode in which Chad and Brian combine their weakened, time-ravaged memories to recap The Invented Part, the first volume in Rodrigo ...

>

Three Percent #177: Eight Books

After a bit of banter about how baseball front offices might be as bad at naming things as book people, and a plug for Paul Vidich's The Coldest Warrior, Chad and Tom each draft four forthcoming books from a total of eight different presses that they've both agreed to read and discuss in future episodes. How could this ...

>

Jewels in Your Pocket [BTBA 2020]

This week's Best Translated Book Award post is from Christopher Phipps, a manager at City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco. We’ve all been warned repeatedly to never judge a book by its cover, a caution easily and often extended towards judgments based on size. Size matters not, counseled Yoda. Big things come in small ...

>

Is It Real? [A January 2020 Reading Diary with Charts & Observations]

It's been sooooo long since I actually wrote something for here . . . I'm not entirely sure how to start! Chad 1.0 would open with something like "$%*# agents" and then go off on a couple individuals who are currently driving me INSANE. Chad 2.0 would come up with some wacky premise that blends ideas behind sabermetrics ...

>

Three Percent #176: Dirty Bookshop

After a bit of a hiatus, Chad and Tom return to talk about the two biggest things to happen during Winter Institute: The American Dirt controversy and the launch of Bookshop.org. If you haven't been following the American Dirt debacle, here are a couple pieces to read: Laura Miller's piece in Slate, Rebecca Alter's ...

>

“Reading Christine Montalbetti” by Warren Motte

As part of a larger series of initiatives involving Open Letter and Dalkey Archive Press, over the next few months, we'll be running a number of articles from CONTEXT magazine, a tabloid-style magazine started by John O'Brien and Dalkey Archive in 2000 as a way of introducing booksellers and readers to innovative writers ...

>

Open Letter Books to Receive $40,000 Grant from the National Endowment for the Arts

Rochester, NY—Open Letter Books at the University of Rochester has been approved for a $40,000 Art Works grant to support Open Letter's Emerging Voice project. This project will result in the publication and promotion of six works of literature in translation from authors with no more than one title already available in ...

>

Homestead Horror and Genealogical Angst [BTBA 2020]

This week's Best Translated Book Award post is from Justin Walls, a bookseller with Powell’s Books in Portland, Oregon who can be found on Twitter @jaawlfins. Psychological horror/thriller/chiller/etc.—you know the sort, taut with spring-loaded tension and positively oozing dread—is tricky to pull off in a work of ...

>

What Did We Have to Talk About, Now That He Was Dead? [CONTEXT]

As part of a larger series of initiatives involving Open Letter and Dalkey Archive Press, over the next few months, we'll be running a number of articles from CONTEXT magazine, a tabloid-style magazine started by John O'Brien and Dalkey Archive in 2000 as a way of introducing booksellers and readers to innovative writers ...

>

Three Percent #175: Biggest News Stories of 2019

On this week's episode, Chad and Tom discuss Tom's recent piece on Jean-Patrick Manchette for LARB and talk about which of his books are best to start with, and why there haven't been more breakout international noir authors. Then they pivot to this Publishers Weekly article on the "Top News Stories of 2019," discussing ...

>

“The Book of Disappearance: A Novel” by Ibtisam Azem

The Book of Disappearance: A Novel by Ibtisam Azem Translated from the Arabic by Sinan Antoon 256 pgs. | pb | 9780815611110 | $19.95 Syracuse University Press Review by Grant Barber This wonderful, important second novel by Ibtisam Azem in English translation came out just in time for the observance of Women ...

>

Dark, Strange Books by Women in Translation [BTBA 2020]

This week's Best Translated Book Award post is from Pierce Alquist, who has a MA in Publishing and Writing from Emerson College and currently works in publishing in Boston. She is a freelance book critic, writer, and Book Riot contributor. She is also the Communications Coordinator for the Transnational Literature Series ...

>

Three Percent #174: Devil’s Bargains

Chad and Tom play a short game on this podcast—when Tom isn't ranting about Amazon. They also discuss Bookshop, when the decade officially ends, favorite translations of the past ten years, Chad's upcoming hiatus from writing for Three Percent, and much more. Next episode Chad and Tom will discuss Tom's recent article on ...

>

Book 6 [The No Context Project]

If you want the context for the "no context project," check out this post, which lays everything out and applies a 20-80 grading scale to "Book 7." Since I really want to get through these mystery books sooner rather than later--so that I can find out what they are and grade myself--I put aside my Charco reading for a bit ...

>

A Couple Turkish Authors [BTBA 2020]

This week's Best Translated Book Award pose is from Louisa Ermelino, who is the author of three novels; Joey Dee Gets Wise; The Black Madonna (Simon and Schuster); The Sisters Mallone (St. Martin’s Press) and a story collection, Malafemmina (Sarabande). She has worked atPeople, Time International, and InStyle magazines ...

>

“Beasts Head for Home” by Abe Kōbō

Beasts Head for Home by Abe Kōbō Translated from the Japanese by Richard F. Calichman 191 pgs.| pb | 9780231177054 | $25 Columbia University Press Review by Brendan Riley Crisp, stark, pristine scenes of gaunt settlements, vast wilderness, and tense human encounters fill this 1957 novel by Abe Kōbō, the ...

>

Three Percent #173: The Poetry in Translation Episode

Anastasia Nikolis (poetry editor for Open Letter Books) and Emma Ramadan (translator, co-owner of Riffraaff) join Chad and Tom to breakdown ALTA 42, talk about poetry in translation, and go on a handful of minor rants—and one major one. (Thanks, Emma!) The Sarah Dessen controversy pops up, as does this article about ...

>

TMR 10.7: “Blossom, Stasis, Spiral, Whoa” [DUCKS, NEWBURYPORT]

This week's Two Month Review was recorded pretty late (on the east coast), so things are a bit loopy. Nevertheless, James Crossley from Madison Books joins Chad and Brian to talk about pages 429-487 of Ducks, Newburyport. They talk a bit about the cultural references in this section—the old movies, Blossom—flip ahead to ...

>

Book 7 [The No Context Project]

A couple months ago, while writing about Suzanne Jill Levine and Jessica Powell's translation of Silvina Ocampo's The Promise, I came up with a sort of crazy scheme: But this gave me a grand idea: What if I could review twenty books from twenty publishers in as blind as a fashion as possible? I wouldn’t know ...

>

How to Launch a Publishing House [Charco Press]

It's Charco Press month! After stepping away from these "monthly themes" for a minute (or, well, actually, a full month), I'm excited to get back to this, and have a bunch of posts planned out for November. If all goes according to plan (spoiler: HA!) I'd like to post a couple interviews with Charco Press translators, a ...

>

Three Percent #172: ALTA 42 Preview

A bit of a disorienting podcast for anyone not attending ALTA, but in this episode, Chad addresses the recent ALTA book fair controversy, and then they go over the general schedule, highlighting a number of interesting-sounding panels, previewing some off-site events, and recommending non-ALTA bars for attendees to hang out ...

>

Perversity’s Politics [BTBA 2020]

Today's Best Translated Book Award post is from Hal Hlavinka, a writer and critic living in Denver. His work has appeared in BOMB Magazine, Music & Literature, Tin House, and others. Some books are made of fucking—of cum and cumming, cocks, twats, and tongues, desires of all kinds. A la Gass, literature may arrive ...

>

TMR 10.4: “Is it Translatable” [Ducks, Newburyport]

Rhett McNeil (translator of Machado de Assis, Gonçalo Tavares, Antonio Lobo Antunes, and more) joins Chad and Brian to talk about the way in which Ducks, Newburyport is less of a single-sentence and more of a never-ending list, about how it is and isn't like Ulysses, about time in the novel, about Ellmann's playfulness, ...

>

Three Percent #171: Can We Go a Week Without an Award Controversy?

This week's podcast is about two kerfuffles: the Booker Prize one and the one between King County Library and Macmillan. There's also some discussion as to why UK book culture allows for critique and small voices to be heard (vs. the American way in which everything is fine), Chad goes on and on about On Becoming a God in ...

>

TMR 10.3: “How Do I Promote This?” [Ducks, Newburyport]

Vanessa Stauffer from Biblioasis came on this episode to talk about the Booker Prize, about the jacket copy she wrote for the Ducks galley, about types of moms, about things in the book that pay off and mysteries that remain mysteries, about the ways in which Ellmann is breaking form and the strong feminist perspective ...

>

Time Does Not Bring Relief

"History is written by the victors" is one of those cliches that's so obviously true that it requires next to no explanation. But the ability to provide evidence for what the victors do when writing history is usually a bit more circumspect and tricky to get ahold of . . . Last Thursday, the Nobel Prize for Literature was ...

>

Three Percent #170: Don’t Give a Million Dollars to a Fascist

This podcast comes in HOT. Lots of talk about how Peter Handke doesn't deserve any award, much less the Nobel Prize. (And if you don't know why, just listen for his quote at the end denying Serb atrocities at Srebrenica by saying "You can stick your corpses up your arse.") Then things transition to an existential conversation ...

>

TMR 10.2: “The Fact That” [Ducks, Newburyport]

Due to an unforeseen illness, Chad and Brian ended up going this one alone, and focus mostly on the way that "the fact that" functions, both in building the character and impacting the reader. Chad asks Brian some craft questions, they debate what makes a book "difficult" (and whether this is difficult or just long), more ...

>

TMR 10.1: “Brave Publishing” [Ducks, Newburyport]

The tenth season of the Two Month Review gets underway with special guest Dan Wells of Biblioasis talking about how they came to publish Lucy Ellmann's Ducks, Newburyport, and the risks involved in doing a 1,020-page book. They also introduce Ellmann--who has one of the greatest bios ever--and the novel itself. Conversation ...

>

TMR 9.10: Monsterhuman by Kjersti Skomsvold (pgs 407-448)

And just like that, season nine of the Two Month Review comes to an end. But first, we have a very nice discussion with Kjersti Skomsvold herself about Monsterhuman, trends in Norwegian writing, autofiction vs. creative nonfiction vs. memoir, authors to read, and much more. (Spoiler: She's just as interesting and charming in ...

>

Available Now: THE INCOMPLETES by Sergio Chejfec and Heather Cleary

“A masterfully nested narrative where writing—its presence on the page, its course through time, its prismatic dispersion of meaning—is the true protagonist.” —Hernan Diaz, author of In the Distance “Now I am going to tell the story of something that happened one night years ago, and the events of the ...

>

Three Percent #169: Year Two of the NBA for Translated Literature

After an update from Chad about his trip to London and Amsterdam, he and Tom break down the National Book Award for Translated Literature longlist, exposing their general ignorance along the way. (They've read, combined, like two of the ten titles?) Also, sure are a lot of Penguin Random House books on these longlists! They ...

>

TMR 9.09: Monsterhuman by Kjersti Skomsvold (pgs 360-406)

Translator Becky Crook comes on this week's podcast to talk about the process of working on Monsterhuman, all the things that she couldn't quite get in there, ones she's very proud of, the reasons why she thinks the book works, and much much more! Only one episodee left! You can watch the Wednesday, September 25 episode ...

>

TMR 9.08: Monsterhuman by Kjersti Skomsvold (pgs 316-360)

This week, Brian is AWOL BUT Patrick Smith brings his A-game. He and Chad talk about the self-conscious humor in Monsterhuman, awkward interactions, the shape and evolution of the narrative as a whole, some info about The Faster I Walk, the Smaller I Am, and much more. A very fun episode that opened as awkwardly as ever . . ...

>

Smelling Books [BTBA 2020]

This week's BTBA post if from Justin Walls, a bookseller with Powell’s Books in Portland, Oregon who can be found on Twitter @jaawlfins. The conceptual artist Anicka Yi's olfactory-based installation Washing Away of Wrongs (2014, created in conjunction with French perfumer Christophe Laudamiel) consists of two ...

>

Flash Sale on Open Letter Preorders!

For a few different reasons—mainly that I wasn't able to get the new excerpt from Sara Mesa's Four by Four online until the WITMonth discount code had expired, but also to celebrate The Dreamed Part being on Kirkus's list of "30 Most Anticipated Fiction Books"—we've decided to have a flash sale on all of our ...

>

Three Percent #168: The 6% Improvement

On this episode, Chad shares some interesting data about the number of books by women in translation before and after the creation of Women in Translation Month, Tom talks about the most recent Amazon controversy, they breakdown the National Translation Award for Prose Longlist (they'll talk poetry in a future episode), and ...

>

“The Nocilla Trilogy” by Agustín Fernández Mallo

The Nocilla Trilogy by Agustín Fernández Mallo Translated from the Spanish by Thomas Bunstead pb | 9780374222789 | $30.00 FSG Review by Vincent Francone Most reviews of The Nocilla Trilogy (written by Agustín Fernández Mallo, recently translated into English by Thomas Bunstead, beautifully packaged by ...

>

Three Percent #167: We Could All Do Better

Meytal Radzinski joins Chad and Tom to talk about Women in Translation Month, depressing statistics, Virginie Despentes, nonfiction in translation, hopes for the future, and much more. As always, feel free to send any and all comments or questions to: threepercentpodcast@gmail.com. Also, if there are articles you’d like ...

>

Women in Translation by Country

Since I skipped last week, I'm going to post a few WITMonth infographics this week, starting with the three charts below. But first, a bit of methodology and explanation. I was curious about which countries were the most balanced in terms of books in translation written by men and women. We know from the earlier ...

>

TMR 9.04: Monsterhuman by Kjersti Skomsvold (pgs 144-180)

Even though the first few seconds ("On today's Two Month Review we'll be talking about . . . ") got cut off, Chad gives his most professional podcast introduction to date, before he and Brian talk about the Nansen Academy, the cyclical nature of chronic illness, the idea of plot points vs. events, and reasons their respective ...

>

Reread, Rewrite, Repeat

Some years ago, I was invited on an editorial trip to Buenos Aires, where we were given a walking tour of the more literary areas of the city, including a bar where Polish ex-pat Witold Gombrowicz used to hang out. The tour guide told us a story about how Gombrowicz hated Borges and would frequently, drunkenly, ...

>

Percent of Translations Originally Written by Women, 2008-2019

I was planning on posting one of these each week with next to no context, but just to explain what's above, this is a year-by-year breakdown of the percentage of works of fiction in translation originally written by men, by women, and anthologies including both genders. The biggest gap was in 2008 (54.61% ...

>

TMR 9.03: Monsterhuman by Kjersti Skomsvold (pgs 92-143)

In this episode, Chad and Brian applaud Kjersti for not getting back together with her ex-boyfriend, talk about circular structures, about the evolution of her written voice, about Antony and the Johnsons, the myth-making behind Babe Ruth, and much more. This week's music is "Patterns Prevail" by Young Guv. Next episode ...

>

Three Percent #166: Women in Translation Month 2019

Chad and Tom drop a number of recommendations for Women in Translation month, some that they've read, some that they're planning on reading. They also discuss possible infographics that Three Percent can produce over the course of the month (if you have any other suggestions, please email), and discuss Chad's new plan to try ...

>

Two Spanish Books for Women in Translation Month

Like usual, this post is a mishmash of all the thoughts I've had over the past week, mostly while out on a 30-mile bike ride. (I need to get in as many of these as possible before winter, which is likely to hit Rochester in about a month.) Rather than try and weave these into one single coherent post, I'm just going to throw ...

>

40% Off All Open Letter Books Written or Translated by Women

Women in Translation Month is always an exciting time to discover, read, discuss, and celebrate books by women from around the world. It was created by Meytal Radzinski back in 2014 (who we're hoping to have on a podcast this month), and has since spawned numerous articles, events, and even the Warwick Prize for Women in ...

>

TMR 9.02: Monsterhuman by Kjersti Skomsvold (pgs 46-92)

One of the funniest TMR episodes in weeks, Chad and Brian crack each other up over writerly anxieties, the sharp wit Kjersti displays in this section, the White Claw Phenomenon, writer vs. author vs. journaler, Kjersti's distain for bad poetry (and TV) about chronic fatigue syndrome, pop culture references from the ...

>

Info on the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards

We're happy to announce the 2020 Best Translated Book Award! All the relevant information is below. Please let me know if you have any questions. Award Dates In terms of dates, this is subject to change, but currently we’re planning on announcing the longlists for fiction and poetry on Wednesday, April 1st, the finalists ...

>

“The Naked Woman” by Armonía Somers

The Naked Woman by Armonía Somers Translated from the Spanish by Kit Maude 168 pgs. | pb | 9781936932436 | $16.95 Feminist Press Review by Rachel Crawford A woman turns thirty, decapitates herself, and after repositioning her severed head onto her neck, wanders through the woods stark naked. In part, this is ...

>

Three Percent Bonus: John Erik Riley

To celebrate Norwegian Month at Three Percent, Chad talked with John Erik Riley, author, photographer, editor of Norwegian literature for Cappelen Damm, and member of the "Blindness Circle." They talk about current trends in Norwegian literature, American comparisons for various authors, a couple really long books, Norwegian ...

>

TMR 9.01: Monsterhuman by Kjersti Skomsvold (pgs 1-45)

The new season of the Two Month Review starts here! Through the end of September we'll be discussing Kjersti Skomsvold's Monsterhuman, translated from the Norwegian by Becky L. Crook. Marius Hjeldnes from Cappelen Damm joins Chad and Brian to provide a bit of background on Skomsvold, on trends in Norwegian literature, on ...

>

Three Percent #165: Disorder in the Book Shelves

This episode of the Three Percent Podcast never gets to its actual topic, but includes minor disagreements about ebooks in libraries and its impact on ebook revenue, more questions about Book Culture's situation, a general sense of malaise, trying to make sense of Dean Koontz, Audible's "Caption" program, a wild idea about ...

>

The All or Nothing of Book Conversation

In theory, this is a post about Norwegian female writers in translation. I know it's going to end up in a very different space, though, so let's kick this off with some legit stats that can be shared, commented on, and used to further the discussion about women in translation. Back in the first post of July—Norwegian ...

>

Dalkey Archive and Graywolf Press [Norway Month]

I initially had some fun ideas for this post—mostly trying to work in my theory of the "2019 Sad Dad Movement" and Elisabeth Åsbrink's forthcoming Made in Sweden, the pitch for which is "How the Swedes are not nearly so egalitarian, tolerant, hospitable or cozy and they would like to (have you) think"—but I think I'm ...

>

Three Percent #164: Rapid Expansion

Chad shares his stupid dreams, Tom questions translators who work for AmazonCrossing and then want indie bookstores to help them out, and they both marvel over Deep Vellum's acquisition of Phoneme Media and A Strange Object (and the launching of the La Reunion imprint). It's a short episode, but filled with great moments, ...

>

Three Percent Bonus: Becky Crook

As part of "Norwegian Month" here at Three Percent, translator Becky Crook (The Black Signs, Monsterhuman, Silence: In the Age of Noise, and many more) came on the podcast to talk about her first cover letter, in which ways she's become a better translator over the past half-decade, what to watch out for in contracts, the ...

>

Three Percent #163: What Do You Want

Chad and Tom talk about a number of interrelated issues related to the costs of bookstore ownership and being a bookseller. They talk about the recent letter from Chris Doeblin at Book Culture, The Book Diaries, Human Rights for Translators, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Internet and Book Culture, and the ...

>

Three Percent Bonus: Ben Lindbergh

In this special bonus episode, Ben Lindbergh of The Ringer and Effectively Wild talks with Chad about his new book, The MVP Machine. They talk about the premise of the book—how player development is the new "Moneyball" and is being driven by players and technology—about the process of co-writing, feedback loops for ...

>

“The Book of Collateral Damage” by Sinan Antoon

The Book of Collateral Damage by Sinan Antoon Translated from the Arabic by James Richardson 312 pgs. | hc | 9780300228946 | $24.00 Yale Margellos Press Review by Grant Barber Author Sinan Antoon is an Assoc. Professor at the Gallatin School of Individual Study of NYU. His undergraduate degree was in 1990 from ...

>

Three Percent #162: I Am a Wild Rose

Chad and Tom are joined by Mark Haber from Brazos Bookstore and author of the forthcoming Reinhardt's Garden (October 1, Coffee House Press). They talk a bit about Translation Bread Loaf (two thumbs up) and about a special poster for anyone who buys the First 100 from Open Letter, before trying their best to breakdown a ...

>

The Five Tools, Part II: Translators [Let’s Praise More of My Friends]

. . . poor translations, he asserted, were the worst crimes an academic or a writer could commit, and a translator shouldn't be allowed to call themselves a translator until their translation had been read by hundreds of scholars and for hundreds of years, so that, in short, a translator would never know if they were a ...

>

The Five Tools, Part I: Authors [Let’s Praise My Friends]

One of the most entertaining parts of my past three weeks of travel was the discovery that Norwegians refer to first-time authors as “debutants.” Which, OK, at first, is weird. The first time someone said it aloud, “she’s a debutant author,” I too had the urge to correct them. But then, like any great joke that's ...

>

Three Percent #161: Will a French Book Win the BTBA?

Chad and Tom took some time off on Memorial Day to bring you this little podcast about the Best Translated Book Award finalists (winner will be announced at 5pm on 5/29 at BEA/NYRF, and there will be an informal afterparty at The Brooklyneer on Houston starting at 7), about the Man Booker International winner, about the ...

>

Autobiography of Death [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Katrine Øgaard Jensen is a founding editor of EuropeNow Journal at Columbia University and the recipient of several awards, most recently the 2018 National Translation Award in ...

>

Four Attempts at Approaches [Drawn & Quarterly]

This post comes to you thanks to a few different starting points: a box of translated graphic novels that Drawn & Quarterly sent me a couple of weeks ago, the fact that Janet Hong translated one of them (see last week’s interview), the fact that I don’t have time this month to read a ton of novels for these weekly ...

>

Spiritual Choreographies [Excerpt]

As mentioned last week, in celebration of the imminent release of Carlos Labbé's Spiritual Choreographies, we decided to make Carlos our "Author of the Month." From now until June 1st, you can use the code LABBE at checkout to get 30% off any and all of his books. (Including ePub versions. And preorders.) And to try and ...

>

“Melville: A Novel” by Jean Giono

Melville by Jean Giono Translated from the French by Paul Eprile 108 pgs. | pb | 9781681371375 | $14.00 NYRB Review by Brendan Riley In The Books in My Life (1952), Henry Miller, devoting an entire chapter to French writer Jean Giono (1895-1970), boasts about spending “several years. . . . preaching the ...

>

Three Percent #160: Double Controversy

One of the calmest podcasts to date featuring two controversial topics: the new Open Letter cover design, and the side-effects of suddenly doubling (or quadrupling) the number of translations published every year. In terms of recommendations, this week Chad is all about the completely wild Bred from the Eyes of a Wolf by ...

>

Dezafi [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. P.T. Smith reads, writes, and lives in Vermont. Dezafi by Frankétienne, translated from the French by Asselin Charles (Haiti, University of Virginia) Every year, the BTBA ...

>

Transparent City [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Tobias Carroll is the managing editor of Vol.1 Brooklyn and the author of the books Reel and Transitory. He writes the Watchlist column for Words Without Borders. Transparent ...

>

Negative Space [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Tess Lewis is a writer and translator from French and German. She is co-chair of the PEN America Translation Committee and serves as an Advisory Editor for the Hudson Review. Her ...

>

the easiness and the loneliness [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Laura Marris is a writer and translator. Her poems and translations have appeared in The Yale Review, The Brooklyn Rail,The Cortland Review, The Volta, Asymptote, and elsewhere. ...

>

Pretty Things [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Giselle Robledo is a reader trying to infiltrate the book reviewer world. You can find her on Twitter at @Objetpetit_a_. Pretty Things by Virginie Despentes, translated from ...

>

Carlos Labbé [Author of the Month]

In celebration of the release of Carlos Labbé's Spiritual Choreographies later this month--and because of a little surprise we'll unveil soon enough--we decided to make Carlos our "Author of the Month." From now until June 1st, you can use the code LABBE at checkout to get 30% off any and all of his books. (Including ePub ...

>

Disoriental [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. James Crossley has stood behind the counter of one independent bookstore or another for more than fifteen years and is currently the manager of brand-new Madison Books in Seattle. ...

>

Bride and Groom [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Ruchama Johnston-Bloom, who writes about modern Jewish thought and Orientalism. She has a PhD in the History of Judaism from the University of Chicago and is the Associate Director of ...

>

People in the Room [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Tom Flynn is the manager/buyer for Volumes Bookcafe (@volumesbooks on all social sites) in Chicago. He can often be found interrupting others' work in order to make them read a ...

>

Congo Inc.: Bismarck’s Testament [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Noah M. Mintz is a translator, a former bookseller, and a PhD student at Columbia University. Congo Inc.: Bismarck’s Testament by In Koli Jean Bofane, translated from the ...

>

Architecture of Dispersed Life: Selected Poetry [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Aditi Machado is the author of Some Beheadings and the translator of Farid Tali’s Prosopopoeia. She is the former poetry editor at Asymptote and the visiting poet-in-residence ...

>

A Guesstimation of a Booklist Review-type Post

I alluded to this in an earlier post, but the main reason Three Percent has been light on this sort of content (and heavy on BTBA content, which is all stellar and worth checking out) isn't due to a lack of desire or interest, but a confluence of other events: deadlines for two pieces (one that should be available shortly, ...

>

Öræfi: The Wasteland [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Keaton Patterson buys books for a living at Brazos Bookstore in Houston, Texas. Follow him on Twitter @Tex_Ulysses. Öræfi: The Wasteland by Ófeigur Sigurdsson, translated ...

>

Three Percent #159: Publishing in 2025?

Chad and Tom are back to talk about Independent Bookstore Day (and Free Comic Book Day and Record Store Day), the Indie Playlist Initiative, fascists storming Politics & Prose, Alex Shephard's Mueller Report article, how much money Stanford (the Duke of the West?) is wasting on their crappy football program instead of ...

>

After the Winter [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Rebecca Hussey is a community college English professor, a book reviewer, and a Book Riot contributor, where she writes a monthly round-up of indie press books, including many books ...

>

Love in the New Millennium [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Rachel Cordasco has a PhD in literary studies and currently works as a developmental editor. She also writes reviews for publications like World Literature Today and Strange Horizons ...

>

Convenience Store Woman [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Elijah Watson is a bookseller at A Room of One’s Own Bookstore. He can be found on Twitter @wavvymango. Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata, translated from the ...

>

Comemadre [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Aaron Bell is a wage laborer and Doctor of Philosophy. Comemadre by Roque Larraquy, translated from the Spanish by Heather Cleary (Argentina, Coffee House Press) Comemadre ...

>

The Governesses [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Pierce Alquist has a MA in Publishing and Writing from Emerson College and currently works in publishing in Boston. She is also a freelance book critic, writer, and Book Riot ...

>

Slave Old Man [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Sofia Samatar is the author of the novels A Stranger in Olondria and The Winged Histories, the short story collection, Tender, and Monster Portraits, a collaboration with her ...

>

The Hospital [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Justin Walls is a bookseller with Powell’s Books in Portland, Oregon and can be found on Twitter @jaawlfins. The Hospital by Ahmed Bouanani, translated from the French by ...

>

The Man Between [Genre of the Month]

I've been very lax in writing about the Open Letter author/genre of the month for April: nonfiction. But, there are still a couple of weeks left to share some info about our previously published and forthcoming works of nonfiction. And, as always, you can get 30% any of these books by using NONFICTION at ...

>

Bricks and Mortar [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Tony Messenger is an Australian writer, critic and interviewer who has had works published in Overland Literary Journal, Southerly Journal, Mascara Literary Review, Burning House ...

>

Season Eight of the Two Month Review: CODEX 1962 by Sjón

If you're a long-time listener to the Two Month Review podcast, or even a part-time follower of the Open Letter twitter, you've probably already heard that the next season of the podcast (it's eighth?!) is going to be all about Sjón's CoDex 1962. "Spanning eras, continents, and genres, CoDex 1962—twenty years in ...

>

Moon Brow [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Tara Cheesman is a blogger turned freelance book critic, National Book Critics Circle member & 2018 Best Translated Book Award Fiction Judge. Her reviews can be found online at ...

>

Three Percent #158: 2019 Best Translated Book Award Longlists

Best Translated Book Award fiction judge Kasia Bartoszynska joins Chad and Tom to talk about the recently released longlists. After providing some insight into the committee's thinking and discussions (and confirming that Chad had no knowledge of the lists beforehand, while not 100% confirming that Chad isn't Adam ...

>

Seventeen [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. Adam Hetherington is a reader and a BTBA judge. Seventeen by Hideo Yokoyama, translated from the Japanese by Louise Heal Kawai (Japan, FSG) In August of 1985, Japan Airlines ...

>

CoDex 1962 [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards. George Carroll is a former bookseller and a West Coast representative for numerous publishers of translated literature. He is currently the curator ...

>

Meet the BTBA Judges!

Tomorrow morning at 10am the 2019 Best Translated Book Award longlists will be revealed over at The Millions. As a bit of a preview, the judges wanted to introduce themselves . . . Keaton Patterson, a lifelong Texan, has an MA in Literature from the University of Houston-Clear Lake. For the past five years, he has been ...

>

Mike Trout Floats All Boats

Let's start with what this post isn't going to be. It's not going to be a post about nonfiction in translation even though I declared, just yesterday, that this is "Nonfiction in Translation Month" at Three Percent. That's really going to kick off next week with a post about two true crime books in translation and a weird ...

>

Are These Clues? [BTBA 2019]

We are days away from finding out which titles made the 2019 BTBA longlist! In the meantime, here's a post from Katarzyna (Kasia) Bartoszyńska, an English professor at Monmouth College, a translator (from Polish to English), and a former bookseller at the Seminary Co-op Bookstore in Chicago. There are simply too many good ...

>

Three Percent #157: Post-Portland AWP